| |

|

|

Introduction

( Says Tuka ) -

Dilip

Chitre |

|

|

|

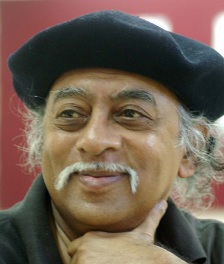

Dilip

Purushottam Chitre (born 1938) is one of the foremost Indian writers and

critics to emerge in the post Independence era. Apart

from being a very important |

|

important bilingual writer,

writing in Marathi and English, he is also a painter and

filmmaker.

Among Chitre’s honours and awards are the Prix

Special du Jury for his film 'Godam' at the Festival des Trois

Continents at Nantes in France in 1984, the Sahitya Akademi

Award (1994) for his Marathi book of poems 'Ekoon Kavita-1' and

the Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize (1994) for his English

translation of the poetry of the 17th century

Marathi poet-saint Tukaram 'Says Tuka'. He was

Member of the International Jury at the

|

|

|

|

| recent Literature festival Berlin, 2001.He

is Honorary Editor of the quarterly ‘New Quest’. |

|

|

Introduction

Part I of

IV

(Says Tuka) |

|

Tukaram was born in 1609 and vanished without a trace in

1650.What little we know of his life is a reconstruction from his own

autobiographical poems, the contemporary poetess Bahinabai's memoirs in verse,

and the latest biographer of Marathi poet-saints, Mahipati's account. The rest

is all folklore , though it cannot be dismissed on those grounds alone. Modern

scholars such as the late V.S.Bendre have made arduous efforts to collate

evidence from disparate contemporary sources to establish a well-researched

biography of Tukaram. But even this is largely conjectural. |

|

|

|

Vithoba-Rakhumai |

|

|

|

There is a similar mystery about Tukaram's manuscripts. The

Vithoba-Rakhumai temple in Tukaram's native village, Dehu, has a

manuscript on display that is claimed to be in Tukaram's own

handwriting. What is more important is the claim that this

manuscript is part of the collection Tukaram was forced to sink

in the local river Indrayani and which was miraculously restored

after he undertook a fast-unto-death. The present manuscript is

in a somewhat precarious condition and contains only about 250

poems. At the beginning of this century the same manuscript was

recorded as having about 700 poems and a copy of it is still

found in Pandharpur.

Obviously, the present manuscript has been

|

|

|

|

vandalized in recent times, presumably by

scholars who borrowed it from unsuspecting trustees

of the temple. It is important to stress that the claim that this manuscript is

in Tukaram's own handwriting is not seriously disputed. It is an heirloom handed

down to Tukaram's present descendants by their forefathers.

Tukaram had many contemporary followers. According to the Warkari pilgrims'

tradition , fourteen accompanists supported Tukaram whenever he sang in public.

Manuscripts attributed to some of these are among the chief sources from which

the present editions of Tukaram's collected poetry derive. some scholars believe

Tukaram's available work to be in the region of about 8000 poems. This is a

subject still open to research. The standard edition of the collected poetry of

Tukaram is still the one "printed and published under the patronage of the

Bombay Government by the proprietors of the Indu-Prakash Press" in 1873. This

was reprinted with a new critical introduction in 1950 on the occasion of the

tri-centennial of Tukaram's departure and has been reprinted at regular

intervals ever since by the Government of Maharashtra. This collection contains

4607 poems in a certain numbered sequence.

In sum the situation is :

i. We do not have a single complete manuscript of the collected poems of Tukaram

in the poet's own handwriting.

ii . We have some contemporary versions but they do not tally.

iii. We have many other versions on the oldest texts and occasionally, poems

that are not found elsewhere.

The various versions of Tukaram's collected poems are transcriptions made from

the oral tradition of the Varkaris and/or copies of the original collection or

contemporary "editions " thereof.

This is a tangled issue best left to the experts. The point to be noted is that

every existing edition of Tukaram's collected works is by and large a massive

jumbled collection of randomly scattered poems of which only a few are in

clearly linked sequences and thematic units. There is no chronological sequence

among them. Nor, for that matter, is there an attempt to seek thematic coherence

beyond the obvious and broad traditional divisions made by each anonymous

"editor" of the traditional texts.

One of the obvious reasons why Tukaram's life is shrouded in mystery and why his

work has not been preserved in its original form is because he was born a

Shudra, at the bottom of the caste hierarchy. In Tukaram's time in Maharashtra,

orthodox Brahmins held that members all varnas other than themselves were

Shudras. Shivaji established a Maratha kingdom for the first time only after

Tukaram's disappearance. It was only after Shivaji's rise that the two-tier

caste structure in Maharashtra was modified to accommodate the new class of

kings and warrior chieftains as well as the clans from which they came as proper

Kshatriyas.

For a Shudra like Tukaram to write poetry on religious themes in colloquial

Marathi was a double encroachment on Brahmin monopoly. Brahmins alone were

allowed to learn Sanskrit, the language of the gods" and to read religious

scriptures and discourses. Although since the thirteenth century poet-saint

Jnandev, there had been a dissident Varkari tradition of using their native

Marathi language for religious self-expression, this had always been in the

teeth of orthodox opposition. Tukaram's first offence was to write in Marathi.

His second, and infinitely worse offence, was that he was born in a caste that

had no right to high, Brahminical religion, or for that matter to any opinion on

that religion. Tukaram's writing of poetry on religious themes was seen by the

Brahmins as an act of heresy and of the defiance of the caste system itself. |

|

|

Indrayani river at Dehu |

|

|

In his own lifetime Tukaram had to brave the wrath of orthodox Brahmins. He was

eventually forced to throw all his manuscripts into the local Indrayani river at

Dehu, his native village, and was presumably told by his mocking detractors that

if indeed he were a true devotee of God, then God would restore his sunken

notebooks. Tukaram then undertook a fast-unto-death praying to God for the

restoration of his work |

|

|

of a lifetime. After thirteen days of fasting,. Tukaram's sunken

reappeared from the river. They were undamaged.

This ordeal-by-water and the miraculous restoration of his manuscripts is the

pivotal point in Tukaram's career as a poet and a saint. It seems that after

this episode his detractors were silenced , at least for some time. |

|

|

Bahinabai |

|

But Tukaram and his miraculously restored manuscript collection both disappeared

after this. Some modern writers speculate on the possibility that Tukaram could

have been murdered and his work sought to be destroyed. However, Tukaram was

phenomenally popular during his lifetime and was hailed as "Lord Pandurang

incarnate" by contemporary devotees like the poetess Bahinabai. Any attack on

his person, let alone a successful attempt on his life, would not have

escaped the keen and constant

attention of

|

|

his

numerous followers. Therefore, such speculations seem wild and sensational.

Shivaji was born nineteen years before the disappearance of Tukaram. The

|

|

| |

Maratha kingdom was yet to be founded when

Tukaram departed from this world.

At this juncture, the whole Deccan region was in the

throes of a political upheaval. Trampled by rival armies and

ravaged by internecine war- |

|

|

Shivaji |

Tukaram |

|

|

fare, small farmers in the village of

Maharashtra faced harrowing times.

Around 1629, there was a terrible famine followed by waves of epidemic diseases.

Tukaram's first wife, Rakhma, was an asthmatic, and probably also a consumptive

woman. Though he had been married to his second wife Jija while Rakhma was still

alive, Tukaram loved Rakhma very dearly. Rakhma starved to death during the

famine while Tukaram watched in helpless horror.

Shivaji was born within a year of the terrible famine that ruined

Tukaram's family as it did thousands of others. Even after Shivaji's rise a few

years later, things could not have been better for the average farmer in the

villages of Maharashtra. Though Shivaji's brief reign was popular by all

accounts, he was battling the might of the Mughal military machine, waging a

constant guerilla war.

Relative peace and stability returned to

Maharashtra only about a century after Tukaram. While it had tenaciously

survived the political turmoil surrounding it, the Varkari religious movement

witnessed a revival only after the situation became more settled. Tukram's great

grandson, Gopalbuwa, played an important role in this revival. Otherwise, for

four generations the history of Tukaram tradition remained obscure even though

increasing numbers of people claimed to have become Tukaram's followers. |

|

|

|

Introduction

Part II of IV |

|

|

|

Contents |

|

|

|