| |

|

| |

| |

Review |

|

|

Shanta Gokhale |

| |

|

Vaze

College in Mulund has a small, well-appointed

auditorium, perfect for an intimate performance.

Its acoustics are so good that every clap in a

shower of applause is heard separately as a

crystal clear drop of sound. The applause at the

end of “Anandovari” shone with that kind of

liquid brightness.

“Anandovari” is a one-man presentation of D B

Mokashi’s 1974 novella of the same name, edited

for the stage by Vijay Tendulkar. Atul Pethe,

the director, is serious about theatre because

he’s serious about life.

His

work over the last decade has arisen out of his

deep frustration with the hypocrisy, corruption,

cynicism and pretensions that have got hold of

our private and public life. His actor Kishor

Kadam too is serious about theatre. Both have

made professional choices that reflect their

personal convictions. Since money comes only to

those who choose to serve the market, their

theatre suffers from an absence of funds. Pethe

overcomes this by clever management of

resources, helped by a music composer and set

and light designers who use the very paucity of

means to create rich effects. |

|

|

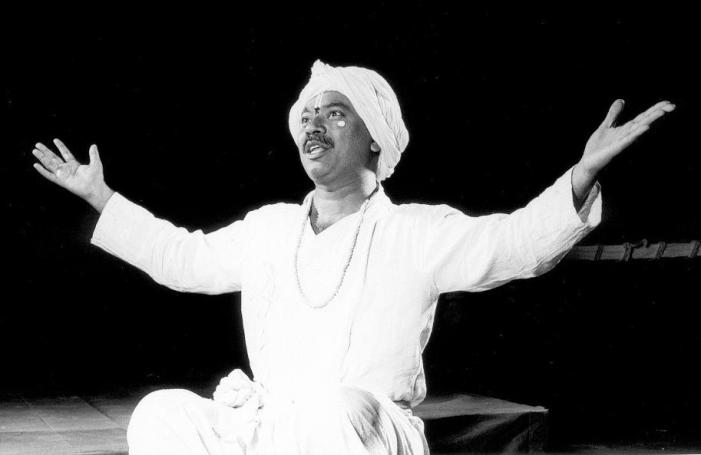

Kishor

Kadam |

|

“Anandovari” is an extended monologue spoken by

Kanha (Kishor Kadam), the younger brother of

Sant Tukaram. Tukaram has disappeared from home

yet again in search of his god, Vitthal. The

distraught Kanha forsakes family, fields and

business to look for his lost brother.

In

the course of the search, he addresses Tukaram,

reminding him of their shared boyhood and

adolescence. He speaks of Tukaram’s early

worldliness, the power and magic of his poetry,

the heavy burden that devotion to Vitthal has

placed on their entire family.

He

confesses that he himself has felt the danger of

this bhakti but pulled out before he drowned. He

chides Tukaram for abdicating his duty as a

householder and head of the family in favour of

a personal search for his god. As it happens,

this is the last time Kanha will go in search of

his brother, for on the third day he finds

Tukaram’s rug and pair of cymbals in a ditch

between two rocks on the banks of his beloved

river Indrayani. That’s it.

Tukaram has disappeared forever, nobody knows

where or how. The play begins and ends with the

rug lying in a spotlit heap at right of stage.

When we see it first, we don’t know what it is.

When we see it at the end, it has become a

potent symbol of worldy tragedy and spiritual

bliss!

That

Atul Pethe should choose to do this play today

is significant in a way that’s not immediately

obvious. But we begin to see its contemporary

relevance when we remember that Vitthal is not a

fair-skinned god. He is the deity of the common

man.

His

devotees, the Warkaris, refer to him as “maulee”

— mother. They have rejected caste and class

divisions. They are all equal before him. No

amount of mischievous interpretation can ever

distort Vitthal into an armed warrior who can be

pressed into the service of divisionists.

Tukaram himself was a shudra, harassed and

socially ostracised by the brahmins of his

village, Dehu, for daring to write devotional

verses at all, and for compounding his sin by

writing them in Marathi when Sanskrit, available

only to brahmins, was the language of the gods.

The

bhakti marg was anathema to brahmins because it

made their mediation with the gods redundant. It

gave people the right to speak directly to their

god without the help of elaborate rituals,

presided over by priests.

Tukaram’s abhangs have permeated the very

language and being of Maharashtra. Vitthal’s

devotees know they cannot be scared into

violence by upstarts pretending to represent

their religion. In doing “Anandovari” today,

pehaps Atul Pethe is reminding us of this. |

| |

| |

Courtesy

: Mid-day December 31, 2002 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|