About the Play

‘Anandowari’ is an important Marathi novel written by Late Di.Ba.Mokashi.Tukaram, as all of us know, was one of the most important Marathi saints from the Varkari Parampara. He resided at Dehu, near Pune.The Vitthal Temple in his house at Dehu, had an ‘Owari’ or ‘Verandah’ outside it. This ‘Owari’ was known as ‘Anandowari’. Saint Tukaram wrote his verses on this ‘owari’. This place was a witness to most of Tukaram’s life. The protagonist and narrator of this play is ‘Kanhoba’, Tukaram’s younger brother. The moment, at which the play starts, ‘Tukaram’ has disappeared as usual. He is possibly lost in some deep spiritual, philosophical trance, which used to happen quite often. Kanhoba used to go in search of his brother on such occasions. However this time he is not able to find Tukaram at the usual places. Kanhoba gets worried. He gets frantic with the thought, that this time he may have ‘lost’ Tukaram forever. While searching for Tukaram, Kanhoba starts recalling the spiritual journey of his brother. He tells us about Tukaram’s life, his sensitive, revolutionary poetry and their relationship with each other. While narrating, Kanhoba, himself a sensitive poet, also throws light on the social conditions, fundamental, philosophical and social issues of that period. Through this narrative, we come face to face with many perpetually important philosophical and social questions and also come to realize the validity of Tukaram’s thought even today.

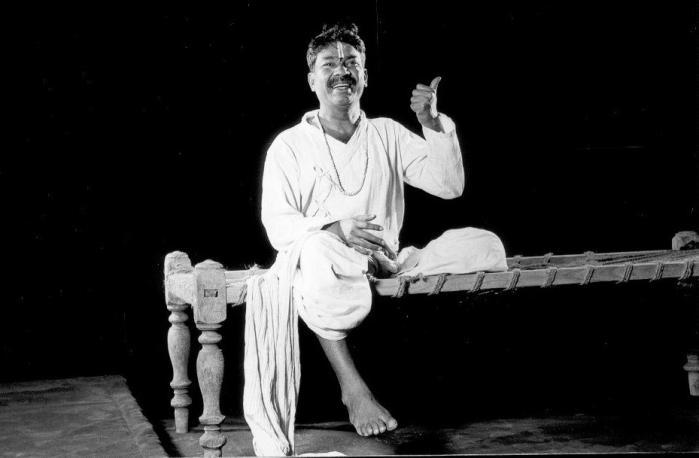

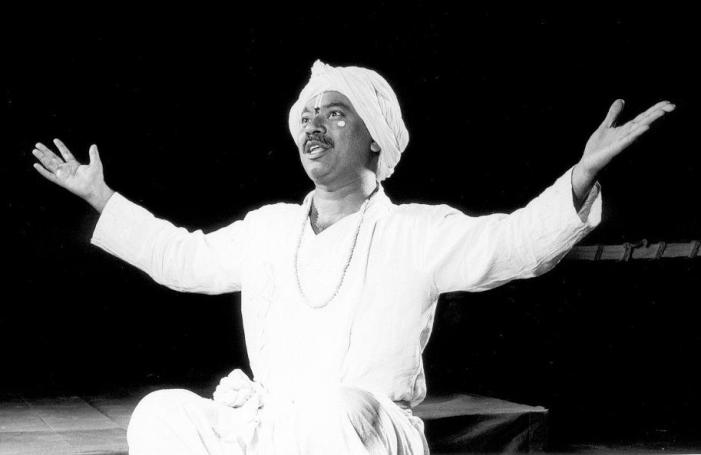

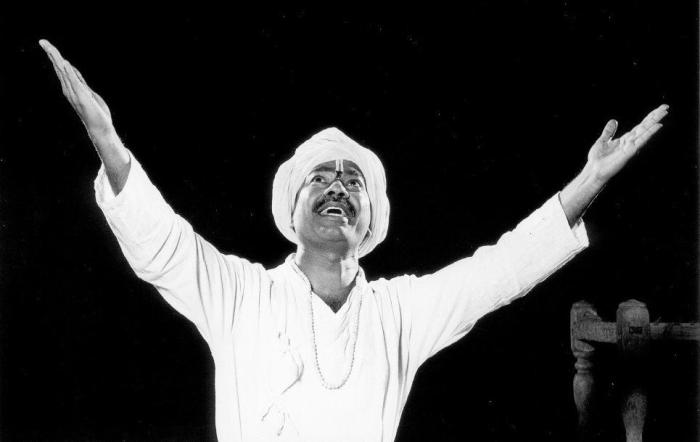

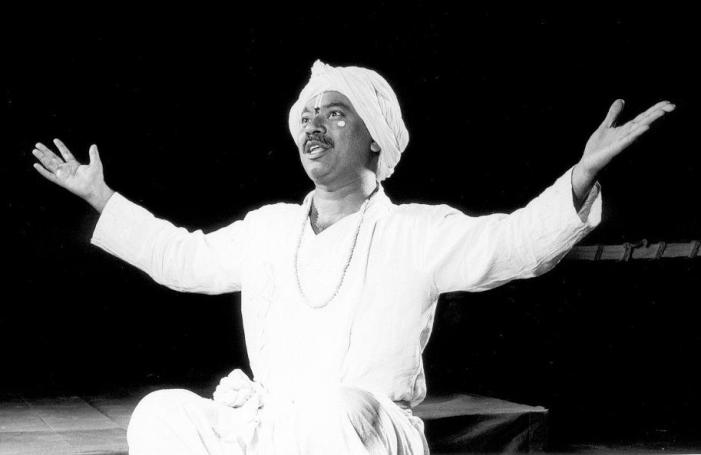

Kishore Kadam ( Actor) & Atul Pethe ( Director)

Credits –

Writer – Di.Ba.Mokashi

Editor – Vijay Tendulkar

Script, Music design and Director – Atul Pethe

Sets – Makarand Sathe

Lights – Shrikant Ekbote and Shivaji Barve

Costumes – Shyam Bhutkar

Music – Ashok Gaikwad

Players – Ashok Gaikwad, Upendra Arekar, Atul Pethe

Production Asst. - Anand, Ashwini, Dhanesh, Pratik, Kausthbh, Shraddha,

Gayatri, Shweta

Back Stage – Pradip

Calligraphy and Photographer– Kumar Gokhale

Special Thanks – Dr.Sadanand More, Prof.Ram Bapat, Gajanan Paranjape,

Meghana Pethe, Jagar and Samanvay Natya Sanstha, Pune.

Production Incharge – Dheeresh Joshi

Sutradhar – Prasad Vanarase

Produced by – Abhijat Rangabhoomi, Pune

Cast - Kishor Kadam

Play time – One hour and forty minutes without interval.

Language - Marathi

Anandowari Script

Writen by : D.B.Mokashi (1915-1981)

Edited by : Vijay Tendulkar(1928-2008)

Theatre Adaptation : Atul Pethe

Translated into English by : Vijay Lele

(The chant of “Rama Krishna Hari” is heard in the background. Kanhoba, Tukaram’s younger brother, is lost in fond memories of Tukaram. He begins to talk about his beloved, rebellious brother to the assembled villagers. These memories are tinged with sadness. He narrates them in the first person. The voices of Tukaram, Kanhoba’s wife and the villagers are heard only at intervening junctures).

Kanhoba: It was Monday, the day Tuka disappeared. It was the second half of a month in Spring. The mornings were still misty out in the field. That day, after cleaning the cowshed and milking the cows, I went to the field to gather grass at the break of dawn. I had carried along my afternoon meal. My sickle was swishing through the grass, and from time to time I hummed tunes based on devotional songs I had composed myself, in typical joy of the poet.

It is He who resides on the banks of the Gomti

Who pulls all the strings of this earthly show

But thoughts of the family were intruding upon me. Just as one can think of spiritual thoughts, one can also think clearly on family related questions, when one is out working in the field. One can give voice to bottled-up anger and disappointments. That’s what I was doing while cutting the grass. I was explaining things to my wife. I was trying to make my sister-in law, Tuka’s wife, understand. Of course, thoughts about my shop too kept straying in. I knew I was measuring my expenditure from a leaking vessel. And thoughts of how Tuka had lost twenty odd days singing about Heaven were also weighing heavy on my mind. I was saying to myself: “Oh Tuka, my elder brother, if only you would pay a little attention to household matters, we could live in such comfort.”

Tuka had been of little use to the family for the last few years. But over the past few days, his renunciation of materialistic matters had grown even more rapidly. I had never seen him so carried away during his religious chanting. His poetry had developed an intensity not noticeable earlier. Like a vice-like grip tightening around your neck, the words of those devotional songs would keep resonating in your mind. Suddenly, in the midst of doing other things, I would catch myself humming the words:

First comes the Lord. The shells and conch adorn Him.

The eagle comes flying in. Fear not, fear not , says He.

The brilliance of His crown and earrings cast radiance all around.

Dusky coloured like a rain-filled cloud, He is a sight to Behold.

O Kanhoba, take care! Do not get so engrossed in these thoughts. This is not your path. Is it Tuka’s path then? When was that decided? Who decided it? I tried to gather back the memories. In his childhood, Tuka used to play all games, with us, like us. Then he started sitting in the shop. A little later, our parents passed away. Remembering days gone by, unknowingly, I began to recollect his life-story.

Kanhoba : This incident occurred at Anandowari, as the verandah around our temple was called. We spent the merry days of our childhood here. It was here that we became knowledgeable adults. Sitting here, Tuka wrote his songs of devotion. And often, at this very place, Tuka and his colleagues would chant the devotional songs he wrote. One night, as the songs came to an end, his disciples urged Tuka thus :

Villagers : “O sir, we want to hear your life story.”

Kanhoba : “Then, overcome with embarrassment, Tuka briefly sketched his life story in the form of fifteen or twenty couplets. I began to sing those couplets. Repeating them time and again, I forgot why I was singing them. This is a common experience while chanting Tuka’s devotional songs. One forgets oneself. I too have composed devotional songs – as Tuka’s brother, as Kanhoba. In fact, many have imitated his “Says Tuka…” style of narration. So these copycats begin with “Says Rama” or “Says Gondya” or “Says Kisha”. When I heard this sort of poetry bursting forth in every house, I stopped composing.

What a scorching day ! I kept cutting grass till the afternoon. I ate in the shade of a tree, drank water from the river. Then I noticed a dried up tree. I cut it to take as firewood. I gathered up the stack of grass, tied up the firewood, put the whole bundle on my head and headed home.

Reaching home, I threw both bundles in the courtyard and entered the house. Inside, Tuka’s wife was sitting with her back to the wall, her legs straight out in front. She was six months pregnant. Her eyes were streaming with tears. Her neck rested against the wall. She was looking vacuously into the distance, clearly surrendered to despair.

Tuka had vanished -- for the second time. In a way, this was not entirely new. Since a full month before this incident, Tuka had made it a habit of leaving home every morning, while proclaiming that he had got a call from Heaven and would soon leave for that abode. Since she was now pregnant, it was no longer possible for his wife to look for her husband up and down those hills. Which is why she was waiting for me to return. She looked up at me. She was exhausted – bearing the burden in her womb and the burden of life with Tuka.

Awali (Tukaram’s wife) : “Brother-in-law!”

Kanhoba: She called out to me but once, and then she began sobbing uncontrollably. My wife stepped in at that point and said:

Kanhoba’s wife: “Brother-in-law Tuka has not returned home since he stepped out yesterday. The children have already checked at the temple, but he is not there.”

The moment I heard this I threw down the sickle in my hand, and without even bothering to adjust the clothes which I had hitched up while working in the field, I stepped out to look for him. I began by looking for Tuka’s cymbals. They were not in place. I rushed to the temple. He was not there. Then I checked at the Anandowari. But I couldn’t find my elder brother or his cymbals even there. Dear Lord! Chanting His name, Tuka goes and sits in some remote corner everyday.

Well, I muttered, let the Lord now find His disciple. Yes, this wayward thought did come to my mind: “Oh Lord, where are you? Are you there at all? You are forever bringing misery into our lives. Tuka keeps searching for you, and I keep searching for Tuka. How much longer are you going to keep creating this confusion? Who will bring home the bundles of grass? Who will store them? Who will milk the cows? Who will go out into the field? Who will sit at the shop? How will this household survive? Will you force a pregnant woman to search for her husband? Then why should she have become pregnant? ”

After saluting the Lord’s image and stepping out of the temple, I began running through the streets of the village. By now the people had grown used to this sight. I heard someone say:

Villager : “Looks like Tuka has got lost again.”

And when I at last found him, someone would say:

Villager : “Looks like he has been found, too.”

Kanhoba : Tuka has got lost. Tuka has been found. What did the villagers know of the terrible travails we went through between these two events? (Angrily) They will understand only when he is not found one day. (Laughing) Then a realization came to me. What will they understand, anyway. Nothing. People have already forgotten those who have come and gone. So also they will forget Tuka. The Lord’s wheel of life keeps turning so quickly.

Emerging from the temple I ran to the river. I stood on the rocky ledge overlooking the Indrayani. The stillness of the afternoon had spread over the river. The light gleamed on the swift current of the water as it ran past.

“Tuka! Elder brother!” Calling out his name, stopping to listen, running up and down the bank, gasping to catch my breath, looking intently at dangerous points along the way, pressing my heaving chest in alarm everytime I caught sight of some object flowing down the river. Who knows how long I kept searching him in this fashion. Then evening descended, and exhausted, I sat on the nearby rocks.

(An eerie silence).

Evening. How often we brothers had sat together as the gathering darkness descended upon this very spot. Savji, Tuka and me. Savji about fifteen years old, Tuka twelve, and I must be about ten. How many years had passed by. The Indrayani still flows past as it used to. The thick bushes on the opposite bank are still standing. Those bushes on the other side of the Indrayani always fascinated Tuka. From time to time, he would look intently at them. I used to feel frightened of these bushes, and I would turn my back on them.

We would already have rounded up the cattle we had taken out to graze. That job had been entrusted to Tuka and me. Savji would accompany us only as an escort. While we kept watch that the cattle was feeding properly, Savji would seat himself on a rocky ledge on the riverbank. Then he would begin singing devotional songs.

Before darkness descended we would turn around the cattle, Tuka and I, and seat ourselves on a boulder beside Savji. Then, as Tuka began to stare intently at the thick bushes on the opposite bank, I would begin to imagine that something horrible was lurking behind the thick foliage, the huge rust-coloured branches, the vines that coiled around them. A variety of high-pitched sounds emanating from there would reach our ears. The river bed would gleam in the blackness. Suddenly a dry branch would snap and fall to the ground with a thud. The nocturnal sounds of the jungle began right from there.

As the evening grew longer and the sky turned red, the bush would turn dark and stand straight like a rampart. I would feel even more frightened, and Tuka, he would keep talking about the bush. He would narrate what he saw in his dreams. In one such dream, he saw that he had crossed the fierce current of the Indrayani river and entered the thicket. As he walked along the beaten track inside the thicket, the portion he had just traversed would gradually vanish. Next, his parents and siblings would disappear, and finally our village Dehu, would get erased. He would be left completely alone!

In another dream, this same thicket would appear to him as a source of strange joy. In the sunlight, against the deep blue sky, he would see a white crane perched atop a solitary branch that had risen far above the bush. The moment Tuka crossed the river and entered the bush, it would get engulfed in a bright light. The songs of birds would fill the air. The trees would bloom with tender, purple and green leaves. Flowers would blossom. The air would turn fragrant. And the beaten track would gradually clear itself to mark a path. He would feel like singing with the birds. His throat would fill up with words. But before the words could burst forth, he would feel choked and awaken from his dream.

Tuka must have told us this dream numerous times while we sat on the rocks. Half my attention would be trained on the cattle which we had herded together and were now standing behind us. I was afraid that if they broke the formation we would not find them in the dark, and they would be eaten by the tiger who was sighted around the village from time to time.

(Savji is singing to the accompaniment of a traditional one-string instrument. The words are extremely moving).

Kanhoba : Savji ! (Silence).

I feel it was under that reddish glow in the sky that we three brothers were moulded into what we would later grow up to be. Our future was decided sitting on that rocky ledge.

Savji later abandoned all materialistic life. But I kept dangling over the sea of life, clinging on to a spiritual branch. Now, sitting on that very rock, it occurred to me that if Tuka was not found, I would be the only one among us brothers left. Where once we three sat together, I would be sitting alone. (After pausing for a moment). This is the destiny of those who go in search of God. This is what happened to Dnyaneshwar and his siblings too. But what does it really mean to go in search of God ?

(The darkness grows).

Total darkness. Even though we do not see it in the dark, life goes on. The parched Indrayani continues to flow in the dry months after Spring. Life does not alter its course to accommodate our limited vision. Even our own blood brother gets lost in the wheel of life. Life knows no brother, no sister, no father. Life has no relation with anyone. But then, who is related to Life? God? That God so beloved to Tuka ? Here, sitting on this rocks near the riverbed, I suddenly remember a fear from my childhood days. Where did that fear disappear? (Pausing) That fear still exists. Only its nature has changed. The fear now is about what might have happened to Tuka. The fear of how everyday life and livelihood will go on.

The moment one remembers everyday life, one remembers the family. (Rises.) People at home will be worried. My sister-in-law must be half-dead with fear. Drawing their children close, both ladies will be huddled together. What shall I tell my sister-in-law on returning.

Then I thought, maybe Tuka has returned home. And he might be worrying about me. He might set out to find me.

Tukaram: “Kanha…”

Kanhoba: (Laughing) The worries of a materialistic man keep performing these somersaults. One person worries about another. Then the other person worries about the first. Worrying about others is something man likes to do. He only feels alive when he worries. Only someone like Tuka can go about, not bothered about wife or family. “Tuka ! Elder brother! ”

As soon as I reached home, I knew that Tuka had not returned. The weak red glow of the lamp was visible from outside. The door was open, but I did not feel like stepping in. With what care we had so often cleaned this house, painted it, oiled the wooden beams! Inside that house were my wife and children. So were Tuka’s wife and children. Yet the whole house seemed sad.

Up above was a night sky filled with stars. For so many years, the same stars must have passed overhead. Yet one had never wondered about them. So what, if there was a sky above. So what, if the stars shone. Let the sun and moon rise and set. We were so happy down on this earth. We were the More children, the children of moneylenders. We had no reason to lack for anything, no reason to grieve over anything. This very bullock cart on which I now sat, we had stayed up one whole night to decorate. While setting off on pilgrimage, we had raced with other carts and emerged winners. Whenever our painted bullock cart took to the road, people would stare goggle-eyed. Each of us brothers had a favourite bullock.

We were still young when we learnt that we were shudras, Kunbis by caste and traders by profession. It was impressed upon us that all this was important to understand. We learnt that our ancestor first came to village Dehu seven generations ago, and that made us ‘Dehukars’. We learnt that we must be proud of our caste. We also learnt that each one must stay within the parameters of his caste. Mother imbibed in us the pride of being moneylenders, while Savji drilled in us the revered place occupied by Lord Vitthal in the More household.

And Tuka? Tuka gave us our childhood ! He was everything for us children. Who would not be fond of Tuka? Everything that a younger brother could want in an older brother, Tuka was all that. The moment you got out of bed, rinsed your mouth and ate a snack, you would run out to play. I would always be hurrying to follow you. The moment you arrived, children would run out from every home, just like the milkmaids ran after the child Krishna. Vitidandu was your favourite sport. But then, you liked all games. When it was your turn to pitch the wooden splint, you would stand really close. Fear was something you simply did not know. And when it was your turn to hit it, the splint would go soaring over our heads.

Sometimes, we boys would go out with the village girls to worship the sand dunes. While they walked ahead singing, we would bring up the rear, playing catch. Tuka knew all the songs the girls sang.

(Song). What’s more, you even knew all the couplets women chanted while grinding the grain every morning. Everyone was impressed with that. When we tied up the swing during the monsoon, you would make it soar the highest and scare the girls.

When the swing soars to its highest, just before it begins to descend, it pauses for a moment, and that is the greatest moment of joy, you would say. And you say, one cannot describe the intense feeling of that moment.

Is that the intense feeling you had experienced, elder brother, when you were once found, in a spiritual dazed state, atop the mountain?

I rose from the platform and entered the house. Face downcast, like some criminal, I quickly crossed Tuka’s wife’s prostrate form, and went further inside. In the kitchen the stove had gone cold. My wife had put our three small children to bed under a quilt. Walking in, I began to heat the stove. My wife followed me. Sitting beside me, taking the twigs from my hand, she quietly asked:

Kanhoba’s wife: “What happened? Did you find him?”

Kanhoba: I shook my head to indicate he had not been found. Then I said, I searched on the river. Tomorrow I will go up the mountain. Stirring the twigs under the stove, her head lowered, my wife muttered:

Kanhoba’s wife: “Brother-in-law will not be found. What evil did I commit in my past life that I should have fallen into this madhouse. But you at least should not lose your head. No, you will not lose your head. Let us leave this village. This house is cursed by Lord Vitthal.”

Kanhoba: “Cursed! That too by Lord Vitthal!” I shouted in anger. “Shut your mouth, you whore.”

(Music. Silence spreads. Then…)

Sometime late in the night I got up, awakened by a dream of Tuka. Even in his youth, Tuka had a round face. And large, round eyes. Thick eyebrows. His eyes held dreams. Several dreams. Not like Savji’s solitary dream. I had dreamt of Tuka’s first day at the counter. Getting up early and full of joy he had accompanied our father to the shop. Tuka… Merchant Tuka …

“Promise to tell me the truth Tuka! In your thirteenth year, when, donning a turban in style, you went and started doing business, was that not because you enjoyed doing it? The moment Savji said he would not mind the shop, did you not step forward. And did not people begin to recognize you as ‘Tuka Sir’, within a year? You too had found Savji’s renunciation of materialistic life an act of madness. Within a couple of years, you began to handle all the business that went with being a trader and a moneylender. Counting the money gave you pleasure. Like a cock who has grown a plume. Every word you uttered, every gesture you made, indicated that you had learnt the intricacies of the business. You had understood man’s desperation to live. Your name had traveled all the way to Pune. Your first wife suffered from asthma. Fearing that she would not conceive children, your father got you married a second time. Your second wife came from a rich family. More importantly, she enjoyed robust health. You did not like her very much, but although you did not agree on many things, you could never resist the sensual pleasure she gave you. Do you not admit this ? Savji denied himself sensual pleasure. But you partook of it happily. Actually, being the elder son, Savji should have looked after the business. But he did not want to sit at the shop. He was quite happy singing and praying. Where was Savji’s wife all this time? Was she ever at our house? In truth, she should have been remembered by all. She was the first of Lord Vitthal’s several victims in our house. I doubt that Savji ever maintained relations with her as a husband.

If Tuka’s last years remain veiled in secrecy, Savji life itself was a secret. How did he discover the knowledge of renunciation even before discovering any other knowledge? Was he born without reproductive organs, like some people are born without a limb? How strange! Just as we never understood him, his wife too must have never had a chance to know him. Lying down there, prostrate, I wondered: Any moment now Savji’s wife might enter from that dark door, and seeing us grieving for not having found Tuka, she would laugh pitifully.

(A long silence. End of the first day).

Rising early, I set out to find Tuka. Tapping my rattle-tipped stick, I made my way once more to the river. Hardly had I walked fifty odd steps than I saw Janya, the village idiot, standing before me. Seeing me, he laughed, and started to yell:

Janya: “Lost… Lost… Tuka is lost again.”

Kanhoba: And yelling in this fashion, he began to dance. Elder brother! When this same Janya went mad, and the village kids ran behind him flinging stones, you often shooed them off and saved him from the torment. And today, the same Janya is dancing because you cannot be found. Elder brother! I had expected some people to rejoice on learning that you were lost, but to think that this idiot should be happy about it!

“Where did you see my elder brother? Tell me. Where? On the other side of the river?”

Without speaking a word, Janya kept repeating the action of someone tucking up his lower garment. Leaving him, I set off again. Behind my back I could hear his mad laughter. Once I thought: he is making fun of me. Then I thought: he is truthfully telling me what he saw. I turned behind to look. Imitating Tuka as he danced, his hands raised as if holding up wooden castanets, he began singing in an atrocious voice. I could not bear to listen to his grating tone. Covering my ears with my hands, I began to run. For over a month, Tuka had been walking about, singing exactly such devotional songs.

Reaching the river, waiting to catch my breath, I stood. But I could not forget the idiot. Tuka would speak to him as if they shared a relationship. Often he would sit watching Janya intently. Once, Tuka said to me:

Tukaram: “ Kanha, if Janya is mad, then everyone should turn mad. While we struggle to attire ourselves, he has shown us that even a loincloth is enough to cover the body. He has taught us that it is possible to live without the love of wife, children and friends. He has proved that it is not necessary to have a house to live in, the blue sky above is quite enough. He has disproved the tenet that the body needs bread and something to eat it with, and that too three times a day. Kanha! He has taught me that everything we cherish as being precious, is actually a myth. He does not even need a God to live by. Who knows! Perhaps what we live is a falsehood, and he is on the right path. Have you noticed, he looks happier than us all.

(A reflective silence).

The tender, red leaves of the Palas have begun to bloom. Wild berries have started to green. A nightingale has been calling out in her shrill note for some time. Elder brother! Just see how Nature is dancing with joy. Seeing her rich splendour you often went crazy. I cannot believe that you have gone away, abandoning Nature. You, of all people, cannot say: what do I have to do with Nature, with Life? You, more than any of us, had lost himself more deeply in it. You had a zeal for life and what you were doing for our family gods was also a part of that zealousness. Like the rest of us common folk, your faith in God too was not untouched with practicality. Then, elder brother, when did you undergo the big change? When?

(Silence)

Everything in our home changed. Like a tree that first loses its flowers, then its leaves, then has its branches drying up, that is what happened to our household. Our once happy home! Since when did it change? The day when some evil eye turned on it? Death! Death does not change every home. But it changed ours! First Father … then Mother… then Savji’s wife! Savji’s wife died and our house became cursed.

Our household was on the road to ruin. Savji’s wife died – she was freed from her sorrow. She died, and Savji left on a pilgrimage. But are there not other households where someone turns a mendicant? And everyone loses their parents someday. And if there was drought, did it hit the More household alone? It hit all of Dehu, the entire region. In every home, someone died of hunger and someone went bankrupt. Then why should this Savji, this Tuka, be born in our house alone?

While climbing up the mountainside, I purposely abandoned the beaten track and sought out little known bypasses. I felt sure that in some thorny bush or craggy nook, I would find Tuka. I reached the mountain top. I sat where Tuka used to sit.

(Assuming a meditative posture).

I am Tuka. I am not Kanha. I am Tuka. Now, where will I head out from here? What will I do? But one cannot peek into Tuka’s life like this and know it in a couple of moments. That is simply not possible. How can I grasp Tuka’s mind? When he disappeared, how far had his thought processes evolved? How did they develop? My mind began to think of all sorts of things that could have happened to Tuka. Could he have stepped into the river in a state of trance, and got carried away? Could a crocodile have dragged him away when he entered the water? Or could he have crossed the river and kept on walking, when suddenly a wild animal sprang upon him? God! Oh God! The devotional songs he had recently been singing in his state of trance began to ring in my ears. He kept bidding goodbye, saying he was going to heaven. “O my brother, goodbye, I am off to Heaven! … I am going, I am going, I am going…” Repeating these words, he would bid farewell to everyone he met.

He would weave a fantasy and create ever new worlds. Suppose another woman begins to like me? This idea once entered his mind and he immediately composed a song on it : “Now I have traversed that desire.” In reality, there was neither such a desire, nor was there any such woman. Similarly, there is neither a divine vehicle to carry him away, nor is there such a Heaven. He would be here, in some thorny bush or stony niche, and I would find him. I was sure of it. Last time I had searched him for seven days. Now, if the need arises, I will search for him night and day.

But why did Tuka become like this? If only those two deaths had not occurred, Tuka would not have become like this. Our father expired suddenly. Tuka had piled up the bullock cart with gunny sacks and gone to do business in the Konkan region. We completed the cremation and were waiting for him to return. The house was steeped in sorrow. Mother had fallen ill and was confined to bed. Tuka returned. He stopped the bullocks in the courtyard outside. He began unloading the sacks. The moment I saw him I exclaimed: “Elder brother!”

Tukaram: “What happened, Kanhya?”

Kanhoba: “Father has passed away!”

Tukaram: “No!”

Kanhoba: Quietly, I came out. I carried in the sacks he had just taken off the bulls. The moneybag was inside. I kept it carefully in the cupboard. Someone has to do these things. Just then Tuka came out, and without even putting on his slippers, began to walk down the road leading to the river. Alarmed, I dropped what I was doing and began to follow him.

We reached the cremation ground, and he stopped. I went up and stood behind Tuka. His eyes were streaming with tears. How Tuka wept! The next time was when Mother died. After that, I don’t remember him ever crying. Suppose those two deaths had not occurred. First Father. Then Mother. The later Tuka was moulded as a result of these two deaths. I am sure of it.

“Tuka, my brother! I cannot fathom the incredible sorrow you demonstrated at the time. Elder brother! Did you not know that no one’s parents live forever? Our parents pass away. Then the parents of our children, we ourselves, pass away. This happens, it is the wheel of life. And so the world goes on. Was it your pride that did not accept this? Or were you so ignorant as not to understand what even a common man understands?”

Of course I did not say all this to Tuka. I sat beside him the whole day. By evening, Tuka had quietened down enough to talk to me.

Tukaram: “Kanha! When father passed away, Mother exclaimed, ‘Oh, why has this happened ?’ I ask the same thing. Why has this happened? Why did Father die? Why did Mother die? How spiritedly I entered business when Savji decided to pull out. I conducted the trade with enthusiasm. I put all my interest into moneylending. I would bring home sackfuls of coins. Father felt fulfilled. Mother caressed me lovingly. But what good did it do? I thought I was managing the business so well. I would continue to bring happiness to our Father. We would live prosperously. Everything would continue happily. Hard work would bear fruit. But what happened instead? What did we get in return? We got wealth. But we lost our parents. All our wealth did not help to ward off their death. Who plucked away our parents from their joyful life and family? Who is this Death? And why is he so uncaring of human emotions? Whatever we human beings may do, Death has no place for us. How frightening all this is! Death ends everything…and we are blissfully unaware of it?”

(Silence. Only the sound of drumming)

Kanhoba: On the one hand my head was full of such thoughts. The sun was scorching. The sunshine under which, while ploughing the field, while cutting the grass, while digging a pit, I would feel my strength increasing rather than decreasing ; the sunshine under which the veins of my hands, my legs, my neck became taut with strength ; the sunshine which seemed so filled with the juice of life, that same sunshine was now arousing completely different emotions. The moment I find Tuka, these emotions will disappear. (Laughs) That is life. The moment our frame of our mind changes, everything appears different. Tuka! … Elder brother…

Drought !

It was during this drought, Tuka, that your first wife died of starvation crying “Food, food!”

In those days, elder brother, you had not yet turned in feverish search of God. You were not even a poet. The handful of saintly persons who now accompany you, had yet to arrive. You faced the famine with the same courage that you exhibited in childhood, when you learnt to play a game you did not know, or the way you astutely dealt with business matters when the responsibility fell on your shoulders. I liked you in that image, elder brother. Even today I like that image of you. Badgered by deprivation, your sorrow on the death of your wife and your son, left you powerless. I had never seen you so powerless. Yet I still liked ‘that’ elder brother. Because you behaved during those crises just as we behaved…and when you became so weak I resolutely took charge of running the household.

And just then, the moneylender came and knocked on our door! It was as if the sky had fallen upon us! But even so, what did it matter, elder brother! Drought ends. Rains return. Crops grow. Trade begins. Moneylending starts, once again. But no! Your world changed completely.

(Stops to dry his tear-filled eyes)

Rains! The rains after the drought! I remember that I was at the foot of this mountain searching for some roots or leaves that we could eat. For some days we had seen clouds roll into the sky overhead, and then drift away. I was praying that the clouds should gather force …

… and then, all at once, the raindrops began to shower down. Letting them strike my face, taking deep breaths, I began to dance… I started to catch the raindrops, catch the falling hail, in my palms. Later, the hailstorm ended and it began to rain fiercely. I just stood there, grateful ! From all four sides I could hear the sweet sound of running water. What I had assumed to be the carcass of a dead cattle, slowly raised its head !

Elder brother! What more does a worldly man like me need to be happy? God should send us rain, corn should grow in the fields, wells should fill up with water, wife and children should be happy, one should be able to celebrate festivals with pomp …what more does one want?

Tell me Tuka, tell me if I am wrong. But I felt all this, and you did not ! You simply got up and started to repair the dilapidated temple in our house. The rains had been good. For an experienced man like yourself, it would have been easy to re-open business. But you never even looked in that direction. Our parents died, you wife and child died, the drought brought us humiliation, people insulted us, it wrenched our hearts. For the rest of us, time brings relief. Wounds get healed.

But you took all this to heart. You kept on mending the dilapidated temple. Whatever money remained in the house, you poured into that. You paid no attention at all to the shop.

We were angry with you. I said to my wife, we need every coin we can earn and here is my elder brother pouring anything we get into the temple. How are we to survive?

Awali, your wife, spoke out then for the first time. Yet , for the first time, you paid no attention to her. You kept repairing the broken temple. Once, when I found you in a transported condition atop the mountain, and unable to stop myself I questioned you on this behavior, you said :

Tukaram: “Kanha! Having repaired the wall, I washed my feet, entered the temple, paid my respects to the Lord, and sat to one side. A villager followed close on my heels, saluted the Lord, and like me sat to one side. Then another villager followed, and did the same. I was astonished, because I did not feel uncomfortable, in the least. After the drought I had become a little afraid of human beings. Every person who came, I thought, had come to ask for something. Often, scared, I would go and hide in the darkest corner of the house. But this time I did not feel the slightest fear of these two villagers. My mind was peaceful! I had entered the temple hundreds of times before that. But it was only then that I realized what a temple truly is. The temple is the only place in a village where business relationships end. A bankrupt man like me enters these four walls inhabited by Lord Vitthal and his consort Rakhumai. My own moneylender also arrives. Yet, before the Lord, everyone becomes equal. Though calling ourselves human beings, we often forget this principle. Kanha! I have decided to drown ‘moneylending’ in the Indrayani!

(Then, with still clearer confidence.)

“Kanha, the man whose property I attach, the man in front of whose house I begin to agitate, his end and mine are eventually the same! Then why should I become a greedy lender and loot somebody? So I have decided to drown moneylending in the Indrayani!

(Silence. Kanhoji, looking into the waters of the Indrayani).

Kanhoba: Elder brother! Everyone thinks I am searching for you because you are my brother. Perhaps they even say, he went to look for his brother because if he did not, it would be contrary to custom. But I know, deep within my heart, why I am looking for you. I seem to be looking for you but I am really searching for what I have lost. Elder brother! I have had a glimpse of what you were searching for. I too have taken a small dip in the pool of renunciation in which you are so completely immersed; and I have emerged, albeit a little scarred. After all, the spirit of renunciation which has so haunted our home has not left me untouched either. Perhaps, completely renouncing the world is a happy state to be in, but there is nothing worse than suffering periodic twitches of renunciation. All at once, materialistic life seems petty, yet one is unable to abandon it.

Elder brother! You wanted to drown moneylending in the Indrayani! Drown moneylending in the Indrayani! I was so carried away hearing your expression, that I went straight into the house to collect the pawned-item registers. As I opened the cupboard, I could feel the eyes of both our wives piercing my back. Just then, one of the children ran upto me and stood by my feet holding the hem of my garment. Looking down at him, I thought: what will happen to these children once the debt registers are drowned ? They will walk hither and thither crying “Food food” ! Will you make beggars of the whole family? Will our drought never end? Elder brother, I fought with you that time. Forgive me. I had not then understood your evolved state of mind. I had not reached a level where I could appreciate your thinking. I did not understand that you were clearing your path, stage by stage.

Whatever a materialistic, self-centred, narrow-minded brother will say, I said to you at that time. You do not care for your wife and children, your brother, your brother’s family, I said. You are reducing to dust the business that our father built through dint of hard work. Many people are non-materialistic. Our brother Savji was non-materialistic. But once his responsibilities were over, he went away. But your family is still around, my family is still around. How can you set out to drown the registers, while the question of their survival still exists?

“Tuka ! Are you setting out to drown your life? Then give me my share of the pawned-item ledgers and do what you like with yours.”

Your face showed pain. You returned to me the registers I had handed over to you. I selected some of the registers and placed the remaining ones in your hand. You went to the water body. You put a stone into the bag and flung the whole lot far away. Those registers must have reached the bottom of the Indrayani. Your face radiated a strange happiness. You had removed some heavy obstacle from your path.

And for some moments after that, a distance like I had never experienced before, came up between Tuka and me. We both stood still by the Indrayani. My mind was in turmoil. I longed to apologise for my mistake, and fling into the water the registers I had kept aside. But I lacked the courage to do it. Consoling me Tuka said:

Tukaram: “ I am not angry with you. Kanha, the sorrows that we see people suffering, are not real sorrows. Sorrows are born of relationships. Those sorrows are false, those relationships are false. The real sorrow is that of birth itself. Hardly does one remove someone’s sorrow, than he begins to grieve over something else. Fulfill one need, and another arises. To remove such sorrows is childish. Kanha, man’s real sorrow lies in something else altogether. Come, let’s go home.

(Silence. Then chanting is heard in the background)

Jai Jai Ram Krishna Hari ! Jai Jai Ram Krishna Hari !

(Praise the Lord ! Praise the Lord!)

Kanhoji: One does not realise how fast days turn into months in the everyday pursuit of survival. Our family size and its problems kept mounting. Sometimes, looking back, one feels that one kept doing the same things over and over. I run the shop now, as my father did before me, and my grandfather did earlier. Like me, my forefathers ploughed the fields and went to cut grass in the field. What came out of all this?

The sun has begun to set on the horizon. Soon it will be night. Is the sun concerned with whether Tuka is found or not? Only man cares about fellow men. The elements of Nature do not bother about him. Elder brother! We are trying to save your body from these emotionless elements. For us, the body is everything. Respond at least once to my cries.

(Apprehensive note in his voice)

Will I never find you now? Where have you so hidden yourself that the place is unknown to me? What will I be left with once you depart? People will be content with your poetry. But I will not be able to read your poems in your absence. Just seeing those pages, I will break down and start crying.

You are more affectionate than the Divine Mother!

More tranquil than the moon !

Thinner than water!

Repository of love !

To the blind the world is forever sightless!

But we who have eyes cannot see!

Shall I tell you something? Reading the devotional songs you have written, I too have begun to compose such songs. I could never fathom how you thought up these devotional songs, one after another. I used to spend a lot of time thinking about what might have prompted you to create a particular composition?

Crush not the flower finding it tender!

Eat not the roots that you so love!

Taste not the water enchanted by pearls!

Puncture not the musical instrument!

How did you always go right to the essence? Does the foundation of your devotional songs lie in Lord Vitthal or in ‘Tuka’? Do these songs occur to you when some thought comes to mind, or when you witness some event? I too would compose a song, prompted by some intense feeling. After that, uninspired, many days would pass by. Sometimes months. I cannot understand how so many new songs come into your mind. Like a honeybee moving from flower to flower, your songs pick the nectar from so many objects and topics. Every moment comes alive in your writing, and turns happy. Tell me, how is it that although my life is full of struggle, you understand better the subtleties of life? As if, the moment it sees you, life opens its innermost petals before you , but closes its petals the moment it sees me?

(Words from Tikaram’s devotional songs …Maaze maana)

The water miracle ! Thirteen days of nightly fasts ! I remember how it happened.

Tukaram: “Kanha, I am going to drown my notebooks in the Indrayani. Whether I am drowning mere paper or poetry, let God, and those who think my devotional songs important, decide. If these words of experience are false, then it is best that they sink to the bottom. That will be a good test of our worth. No man can be deemed an intellectual or an ignoramus on account of his birth alone. Our mouths can be sealed on the strength of muscle power, but not our minds or our souls. All tyrants committing injustice behave just like this. But why should we fear?

Chokhoba, Dnyanoba, did they fear? Everyone knows there is butter in curd. But only he who knows how to churn, will succeed in extracting the butter. Will fire be ignited by itself in wood. Someone has to rub and create the friction, isn’t it? Only by extracting the stones from the wheat will we get good flour. Only by suffering hardship can one safeguard the field. If one does not think about these rules, respect these codes of behaviour, one cannot benefit. Only if man makes the necessary motions can he ward off the dangers that surround him. I chant the Vedas and some Brahmins prostrate themselves before me – thus does religion fail. If my folly is that I cannot accept the fraudulent teacher-disciple relationship, then I must suffer for it. Even if I resist, they will force me to do it. So, I have now placed my faith in God and the ordinary people, Kanha.

(Music)

Then the water miracle transpired. The immersion of the notebooks had been done. The fasts were completed. And then, the notebooks floated back to the surface! Safe despite their immersion in water. Who can say why they surfaced? Perhaps a turtle or a crocodile happened to dislodge the stone you had kept on the pile of notebooks. Or, as later people began to say, the Lord himself removed the notebooks and held them up before you. Oh God!

(Silence)

The fact that you were not near me in this darkness, by the river, was a source of intense pain. Now that I had partly realized what you really were, I was thinking how joyous it would be if I found you! What you had been saying was true. This existence is false. Everything here is false. Look! It is already forty years since we have been together, and within fifteen or twenty years more, neither of us will survive. Like Father. Like Mother. They disappeared. Savji went away. Everyone has come to this world only to depart. Where did they come from? Where did they go? These thoughts troubled you endlessly. Your persistence to know was born of exactly this quest. It was a search to understand where did all life go?

You were taking deep dives into life. Sitting on the bank of the pond during our childhood, I would watch you and ask “Elder brother, did you touch the bottom?” Gasping for breath, you would bring your head to the surface spitting out the water, and shake your head to say, “No, no!” That is what I was remembering now. At several places you would shout “Found it , found it” and emerge with your fists raised above the water, but when you opened your hands they were empty. At other times, your hands were grasping at something, but I was unable to comprehend.

(Silence. End of the second day).

This was the third day of my search for Tuka ! On the third day of the search, once again, I reached the banks of the Indrayani. Following me, Rameshwarbhat, Bahinabai’s husband, Mumbaji, arrived on the site. Everyone was silent. No one would say a word. Unbearable silence. Then, taking courage, someone said:

Villager: “It is said that Tuka ascended to heaven in his bodily form. A shepherd boy apparently saw the flying vehicle which bore him away. Others say Tuka jumped into the pond. Still others say a crocodile carried him off. Some claim that he simply walked away. A few say…”

Kanhoba: “I could no longer hear anything. Darkness gathered before my eyes. I felt the ground beneath my feet begin to tremble. A cacophony of voices began to roar in my head. I could not bear the thought that I might never see Tuka again. I began to make my way rapidly up the Indrayani river, alone. My mind was in turmoil. How could Tuka, my elder brother, disappear like this – this question kept reverberating in my head. My mind was full of suspicions. But who knows, perhaps the Lord really did take him away. But where? Elder brother…!

(Silence)

(Kanhoba seems to see something. He starts running. Suddenly he spots Tukoba’s cymbals and blanket. He holds them tightly against his chest. A sob is wrenched from his heart. He comes running back home and stands in front of the idol of Lord Vitthal. He is trembling violently in anger).

Why, you destructive Narayana! So you have targeted us for your trials. Black face! You have brought our entire family to ruin. Why, pray? Are you doing whatever comes to your mind because you think we can do nothing ?

(Quickened music. Dheend dheend….Then suddenly, silence).

Two days have passed since Tuka has gone. I am constantly walking up and down the house. My eyes, instead of seeing the objects in the house, remain riveted on memories associated with him. Here we were born, grew up, laughed, sulked, ate, played, wrestled, exulted, enjoyed.

( Begins to cry).

“Oh God ! Just the other day I was mad at you, I lost my mind. I prostrate myself before you. Forgive me. Now, that anger has disappeared. Hereafter, I shall spend my days caring for my wellbeing, raising my children. Singing Tuka’s songs I shall behave responsibly. Oh Lord ! Whether you exist or not, whether you bless us or not, none of these thoughts concern me. If you exist, fine, please stay peacefully in your abode, and I will stay in mine. Even though I am the only brother now surviving, I do not blame you. Which village do you reside in? Tuka was inquiring after you. He went in search of your village. He left without completing your song. I am now stepping into the world singing your song. Until I am united with my brother, grieving for him, I shall continue to chant your name with the same intensity as Tuka.”

(One hears the sounds of the veena. Followed by the pakhwaj and taal. A traditional song of devotion begins. The notes of the Bhairavi begin. Fade out…)

END

From Socrates to Tukaram

Sanjay Pethe

Noted theatre director Atul Pethe is at it again. After "demystifying Socrates" with the highly acclaimed 'Surya Pahilela Manoos' and after probing the ideals and the reality of Dalit movement with 'Ujalalya Disha', he has turned his attention to Tukaram, the presiding poet-saint of the state from the 17th century. He directs the play 'Anand-owari', which opens at the S.M. Joshi hall on Sunday evening.

Like most of his earlier efforts, Pethe has chosen to work with heavyweights. Based on an acclaimed novel of the same name by D.B. Mokashi, the play is "edited" for theatre by none other than Vijay Tendulkar, arguably the grand-dad of modern Marathi playwrights. And if Shriram Lagoo returned to theatre with a bang as Socrates, despite his septugenarian status, 'Anand-owari' shall mark a crescendo for national award-winning Kishor Kadam of 'Gandhi v/s Gandhi' fame and 'Dhyasparva'.

Incidentally, when Tendulkar started working on the script as early as in 1988, he had Dr Lagoo in mind. Sunday's premiere has thus been an elusive dream of Pethe's for the last 15 years. In the interim, it got off to several false starts with Nana Patekar, Sayaji Shinde and Ganesh Yadav vying to perform the solo act.

Pethe and Kadam had been constantly toying with the idea for the last five years, until they decided to drop everything else for a month and a half , and stage it under the Pune-based Abhijat Rangbhoomi banner. So what is it about the play that keeps celebrated artists hooked for 15 years? It is the challenge of analysing the human aspect and relevance of the saint, whose songs are sung in every household in the state, a whopping 350 years after he wrote them.

Kanhoba (played by Kishor Kadam)

Pethe and company brook no excuse for popular appeal while analysing Tukaram through the eyes of his younger brother Kanhoba (played by Kadam). In the process it takes a painstakingly objective view of Tukaram's transition from being an ordinary man, to being hailed as a saint and poet-extraordinaire.

It's as demanding a play to watch as it is to stage. Even as it showcases Kadam amazing talent, Pethe's team of architect Makarand Sathe (set design), Shrikant Ekbote (light design) Sham Bhutkar (costumes) music (Ashok Gaikwad) keep the viewers busy in reading beyond the lines.

Review

Shanta Gokhale

Vaze College in Mulund has a small, well-appointed auditorium, perfect for an intimate performance. Its acoustics are so good that every clap in a shower of applause is heard separately as a crystal clear drop of sound. The applause at the end of “Anandovari” shone with that kind of liquid brightness.

“Anandovari” is a one-man presentation of D B Mokashi’s 1974 novella of the same name, edited for the stage by Vijay Tendulkar. Atul Pethe, the director, is serious about theatre because he’s serious about life.

His work over the last decade has arisen out of his deep frustration with the hypocrisy, corruption, cynicism and pretensions that have got hold of our private and public life. His actor Kishor Kadam too is serious about theatre. Both have made professional choices that reflect their personal convictions. Since money comes only to those who choose to serve the market, their theatre suffers from an absence of funds. Pethe overcomes this by clever management of resources, helped by a music composer and set and light designers who use the very paucity of means to create rich effects.

Kishor Kadam

“Anandovari” is an extended monologue spoken by Kanha (Kishor Kadam), the younger brother of Sant Tukaram. Tukaram has disappeared from home yet again in search of his god, Vitthal. The distraught Kanha forsakes family, fields and business to look for his lost brother.

In the course of the search, he addresses Tukaram, reminding him of their shared boyhood and adolescence. He speaks of Tukaram’s early worldliness, the power and magic of his poetry, the heavy burden that devotion to Vitthal has placed on their entire family.

He confesses that he himself has felt the danger of this bhakti but pulled out before he drowned. He chides Tukaram for abdicating his duty as a householder and head of the family in favour of a personal search for his god. As it happens, this is the last time Kanha will go in search of his brother, for on the third day he finds Tukaram’s rug and pair of cymbals in a ditch between two rocks on the banks of his beloved river Indrayani. That’s it.

Tukaram has disappeared forever, nobody knows where or how. The play begins and ends with the rug lying in a spotlit heap at right of stage. When we see it first, we don’t know what it is. When we see it at the end, it has become a potent symbol of worldy tragedy and spiritual bliss!

That Atul Pethe should choose to do this play today is significant in a way that’s not immediately obvious. But we begin to see its contemporary relevance when we remember that Vitthal is not a fair-skinned god. He is the deity of the common man.

His devotees, the Warkaris, refer to him as “maulee” — mother. They have rejected caste and class divisions. They are all equal before him. No amount of mischievous interpretation can ever distort Vitthal into an armed warrior who can be pressed into the service of divisionists.

Tukaram himself was a shudra, harassed and socially ostracised by the brahmins of his village, Dehu, for daring to write devotional verses at all, and for compounding his sin by writing them in Marathi when Sanskrit, available only to brahmins, was the language of the gods.

The bhakti marg was anathema to brahmins because it made their mediation with the gods redundant. It gave people the right to speak directly to their god without the help of elaborate rituals, presided over by priests.

Tukaram’s abhangs have permeated the very language and being of Maharashtra. Vitthal’s devotees know they cannot be scared into violence by upstarts pretending to represent their religion. In doing “Anandovari” today, pehaps Atul Pethe is reminding us of this.

Courtesy : Mid-day December 31, 2002

1. Anandowari Revisited

G. P. Deshpande

G. P. Deshpande, Marathi playwright, was born in 1938 in Nasik, Maharashtra. He received the Maharashtra State Award for his collective work in 1977, and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for playwriting in 1996. Prof. Deshpande is known for advocating strong,

progressive values not only through his academic writings but also through his creative work. His plays especially reflect upon the decline of progressive values in contemporary life. Having specialized in Chinese studies, he was head of the the Centre of East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. The Library of Congress has acquired twelve of his books including a few on Chinese foreign policy. Some of his works have been translated into English.

Anandowari Revisited

In a remarkable piece of polemic Maharshi Viththal Ramji Shinde (1873-1944), an early twentieth century thinker and political and social activist, summed up the state of Marathi letters thus : Marathi language (and literature) was alive (and prosperous) from Jnandadev (1275-1296) to Tukaram (1609-1650). (From the 13th to the 17th century that is). He then went on to list the people responsible for its decline that followed. He has actually held them responsible for ‘strangling’ the Marathi language! His detailed list of culprits responsible for such a heinous act against the genuine creative urges of Marathi and of course, innocents among the Marathi authors is not important for our argument. The fact is that there was something that the colonial period did to our creativity which resulted into a crisis of the arts especially of literature. I do not think that it is in the main due to our moving away from nativism. More likely it was due to the general colonial tendency to trace the cultural crisis to our image of ourselves. The colonial logic generates an image of the conquered acceptable to the colonizers.

It is accepted wisdom that writing in Indian languages begins with poetry. Strangely Marathi is perhaps the only Indian language which can boast an antiquity for its prose writing that is as old as that of its poetry. The Mahanubhava prose writing dates back to the thirteenth century. Considered to be the first work in Marathi - Vivekasindhu (An ocean of thoughts) by Mukundaraj. But Mahanubhava writing is comparably ancient.

It is therefore not strange that Shinde, well versed in the literary tradition of Marathi took umbrage at the scant regard that the “modern” writing showed to this tradition or to its elegance and achievements. Small wonder then that Shinde rather ruthlessly attacked the literary mavericks as also the serious writers and nearly dismissed them from the hall of fame of the Marathi belle letters.

The pale romanticism that dominated the Marathi literature during the colonial period was made worse with the rise of a rather lifeless “new and standard” language during the colonial period. It was really in the post-independence period that the Marathi literature especially prose seemed to acquire a new life-line. The fifties through seventies of the last century suddenly saw a rise of newer and fresher forms of writing. Fiction came into its own. The famous and much celebrated authors of the new fiction were Gangadhar Gadgil (1923-2008), Arvind Gokhale (1919-1992) and others. At the same time traditional narrative forms also acquired a new strength and life. Vyankatesh Madgulkar (1927-2001) and Digamber Balkrishna Mokashi (1915-1981) were the principal exponents of the latter school. It is not modern or new in the sense Gadgil’s fiction was. It was in many ways an expression of modernized tradition. Its main thrust was to demonstrate that a simplified version of a movement from the dated and pre- industrial oriental tradition to a modernity of industrial and material world was the modern impulse. What authors like Mokashi and Madgulkar achieved was to rid the literary history of the linearity that the nineteenth century seemed to have straitjacketed it into.

Mokashi thus is a writer who along with Madgulkar gave a new lease of life to the world of Marathi letters. As quite often happens, Mokashi never got his due recognition. He remained an unsung hero of Marathi fiction His work Anand Owari is in many ways the statement of modernized tradition. This rendering of that work in dramatic mode is a tribute to Mokashi that has been due for a while. It is to be welcomed that the dramatic rendering is now available in a film. Vijay Tendulkar (1928-2008), easily the most celebrated of modern playwrights of India. He was also an admirer of Mokashi’s work. But that is not all. He has edited Mokashi’s work with a sensitivity that is new to Marathi literature.

The story that Mokashi narrates in this work is the quintessentially central point of debate in modern Marathi. What does one make of the Bhakti tradition of medieval literatures of India? Of course it has posed different problems in different language areas of India. In Marathi the debate has centred on the contradiction between Pravritti (initiative and action) and Nivritti (resignation and withdrawal) Mokashi in a sense relives that debate through Kanhoba, the younger brother of Tukaram, easily one of the greatest poets of Marathi ever. Kanhoba poses the tension between the mundane world of crass materiality and the spiritual or mystic renunciation of that world. Kanhoba emerges in this narrative Tukaram’s alter ego of sorts. In a sense this narrative rejects the modern day versions of the debate like the one of nationalist historian Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade (1863-1926) or a protagonist of the mystic (Mumukshu in Marathi) tradition like Laxman Ramchandra Pangarkar (1872 - 1941). This story establishes the dialectical nature of that engagement. Understandably the nationalist zeal of that debate can be easily dehistoricised and misunderstood today. Indeed that is happening today. But it appears that Mokashi’s Kanhoba is asking the same question more pointedly and poignantly.

Kishor Kadam as Kanhoba in the play Anand Owari

Like the questions of political power and its renunciation that Rajwade found relevant in his discussion of the Sant Kavis (the Bhakti poets of Marathi) Kanhoba in his grand soliloquy is posing the question if the materiality of the world and its mundane compulsion can be wished away at all. Kanhoba is caught in a trap of that mundane world and his beloved brother losing himself in his Bhakti and his Vithoba, the Lord standing akimbo at Pandharpur aptly described by Guy Deleury in his introduction to the French translation of selected poems of Tukaram ( Tukārāma: Psaumes du pèlerin [French] (UNESCO Collection of Representative Works) / Guy Deleury / Paris: Gallimard [France], 1956.), as the Jerusalem of the Marathas. Mokashi celebrates that.

Kanhoba lends poignancy to Mokashi’s work which sums up the dilemma that paradoxically has made Tukaram the most loved poet of Marathi. In the end there is no answer to Kanhoba’s predicament or the entanglement in the mundane world and the spiritual quest. He cannot resolve it the way his brother did or could. At times in Mokashi’s work, he seems to be uncertain if his brother really ever solved the dilemma. For Mokashi’s Kanhoba, the quest is not over nor is it ever likely to be over. His Parabrahma (supreme reality) is distinct and different from Tukaram’s.

Well, in short this is a major work and it should indeed be celebrated that at least an edited version is now available in English. For far too long has our discussion and appreciation of the Bhakti literature has got stuck in clichés. Kanhoba, Tukaram and Mokashi would get us out of the clichés. May be we shall discover the points of strength of modernized tradition and its literature. Let Anand Owari be a voyage of discovery of Kanhoba, and no less Mokashi.

2. The Existentialism of Tukaram

Prachi Bari

Set in a contemporary style, Atul Pethe's play on Sant Tukaram, taken from the book Anandowari, explores his dilemmas as an ordinary man and his transformation.

Atul Pethe is all geared up to attend the National School of Drama's (NSD) International Drama Festival 2003, for the fourth time in Delhi.

Pethe is a director, actor and a writer of repute and has been involved with theatre for more than 20 years. His play Surya Pahilela Manoos, where Dr Shriram Lagoo plays the role of Socrates, won rave reviews and was recognised at the NSD's first National festival. This time, his play Anandowari has been selected for the festival, which will also have plays from Singapore, Japan, Sri Lanka and Germany.

Anandowari is a well known Marathi novel, written by D B Mokashi which deals with Kanoba, Sant Tukaram's younger brother, who is trying to locate Tukaram, who has disappeared. The novel deals with the spiritual journey of Tukaram, his life, revolutionary poetry and their relationship with each other.

"This play has possessed me for the last 13 years. There are various levels in which this novel can be deciphered. Also, there are many viewpoints presented through just the character of Kanoba," Pethe explains.

"Tukaram's story has been rendered in a very different perspective, and my play gives an intense portrait not only of Tukaram the man, but also of the restlessness of a creative and rebellious person. Kanoba seeks to understand this and shows us the picture of this different Tukaram, one we can all relate to," he adds.

Pethe further says that this play raises questions related to our lives and makes us introspect. It explores the pain and agony of human life. "I always found the fact interesting that Tukaram was a person like us, but he is transformed witnessing the life around him, thus making him look for the meaning of true life and exploring other domains, in turn renouncing his life. Kanoba, his brother, on the other hand continues to be a part of this world and explore its complexities," he says enthusiastically.

Pethe loved the challenge of dramatising the novel into a play. He has written at least five to six versions of this novel to turn it onto a one man show, with Kishore Kadam playing the role of Kanoba. "I had planned this play with Nana Patekar in mind 13 years back, but he became busy with Ankush and the play stayed where it was... in my mind, till now," Pethe tells us.

Kishor Kadam as Kanoba

This play was dealt as an experimental play which has been moulded to the present day scenario and is relevant to today's condition and philosophical debates. The language of the playas well as the original novel is very lyrical and intense, and even though there is a single character speaking, the play moves freely between the past and the present with nature playing a pivotal role.

"We have tried to explore space and time with our set designs, lighting, costumes and music. It was worth exploring the possibility of relating and reinterpreting this rebellious character to our present day situation," he concludes.

Courtesy : The Times Of India 19th February2003.

3. Kishor Kadam, the actor

Sanjay Pendse

Kishor Kadam belongs to the second generation of non-chocolate heroes of Indian theatre and cinema. Following in the footsteps of Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri, this new tribe enjoys a happier double life — in terms of full-time careers straddling screen and stage, and art-house and mainstream productions. Incidentally, Kishor is also an acclaimed Marathi poet and writes under the nom de plume, Soumitra. But things were not as happy for Kishor, in his early days, at the modest fisherman’s cove of Khar Danda in Mumbai. He was a wild-card entry, in every sense of the word, into Marathi’s highly competitive college theatre scene. Theatre guru Satyadev Dubey noticed him and groomed him in his acting school, where Olympian efforts on voice and diction (at least in Hindi-Urdu, Marathi and English) are de norm. Countless hours of practice and dedication helped him shine on Mumbai’s ‘art’ circuit, with productions like Bambai ke Kowwe. But his ticket to national fame was the role of Devdas Gandhi, the Mahatma’s son, in Gandhi v/s Gandhi..., and more recently Dhyasparva, Amol Palekar’s biopic on India’s family planning pioneer R.D. Karve. One is tempted to compare Kishor's earthy appeal and intensity to Denzel Washington’s, though it might be a tad early to do so.