Notes on Tukaram - Mahatma Gandhi

SPEECH AT SECOND GUJARAT EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCE BROACH. October 20, 1917.

These three great speakers have acquired this power of eloquence not from their knowledge of English but from the love of their own language. Swami Dayanand did great service to Hindi not because he knew English but because he loved the Hindi language. English had nothing to do with Tukaram shedding lustre on Marathi. Premananda and Shamal Bhatt and recently, Dalpatram, have greatly enriched Gujarati literature; their glorious success is not to be attributed to their knowledge of English. The above examples prove beyond doubt that, for the enrichment of the mother tongue, what is needed is not knowledge of English but love for one’s own language and faith in it.

LETTER TO MAGANLAL GANDHINAVAGAM.

Thursday, July 25, 1918.

CHI. MAGANLAL,

The love taught by Swaminarayana and Vallabh is all sentimentalism. It cannot make one a man of true love. Swaminarayana and Vallabh simply did not reflect over the true nature of non-violence. Non-violence consists in holding in check all impulses in the chitta It comes into play especially in men's relations with one another. There is not even a suggestion of this idea in their writings. Having been born in this degenerate age of ours, they could not remain unaffected by its atmosphere and had, in consequence, quite an undesirable effect on Gujarat. Tukaram had no such effect. The abhangas of Tukaram admit ample scope for manly striving. Tukaram was a Vaishnava. Do not mix up the Vaishnava tradition with the teaching of Vallabh and Swaminarayana. Vaishnavism is an age-old truth.

Blessings from BAPU

LETTER TO PREMABEHN KANTAK

June 17, 1932.

CHI. PREMA,

Personal experience is more important than the influence of external circums-tances. The latter should have no effect on a votary of truth. He ought to see beyond them. We often see that opinions formed on the basis of external circumstances are afterwards discovered to be wrong. The connection between the atman and the body is a well-known instance of this. Because the atman is intimately connected with the body in this life, we cannot easily think of it as distinct from the body. No one has equalled the power of vision of the person who saw beyond this outward fact and first uttered: "Not this". You will be able to think of any number of such instances. It is not at all proper to take literally the utterances of Tukaram and other saints. Recently I read one such utterance of Tukaram. I quote it for your benefit. An image of Lord Pashupati is made out of clay: what, then, would clay called? The worship of the Lord reaches unto Him, the clay remains clay. An image of Vishnu is carved out of stone, yet the stone does not become Vishnu. The devotion is offered to Vishnu, the stone remains a stone. From this, I draw the lesson that we should pay attention only to the idea behind the words of such saints. They may describe personal God and yet worship the formless. We ordinary human beings cannot do that and, therefore, we would come to grief if we do not try to understand their real meaning and guide ourselves by it.

BAPU FOREWORD TO "TUKARAM KI RASHTRAGATHA" SEVAGRAM,

January 10, 1945.

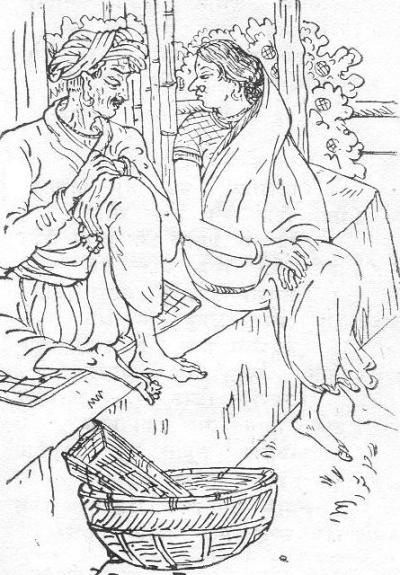

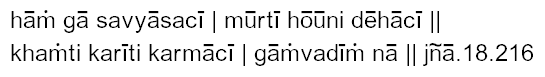

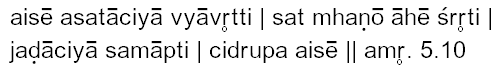

Dr. Indubhushan Bhingare had published earlier the first edition of Sant Tukaram ki Rashtragatha. The present edition is the revised one. My knowledge of Marathi is very slight. I like Tukaram very much. But I could read only a few of his abhangas without effort. I therefore passed on Dr. Bhingare's selection to Kundarji Diwan who took great pains to go through the whole thing. The Gatha needed a fitting picture. Dr. Bhingare had selected a cheap one. It hurt me very much. I sent it to Shri Nandalal Bose, the renowned Santiniketan artist. He has been kind enough to send me pictures of Tukaram to go with the abhangas. I sent the one that I thought the best among them to Bhingare and it will be published in this edition. I hope this edition will command the respect of people.

M. K. GANDHI

Tukaram on Bhandara -Nandlal Bose |

Tukaram and wife Jeejai - Nandlal Bose |

LETTER TO PARACHURE SHASTRI

BIRLA HOUSE, BOMBAY,

April 15, 1945.

SHASTRIJI,

You have fallen ill! It is not good if it is from worry. But if it is death calling, there is no harm. "You must go with a smile on your lips." And that too from a Lepers' House . Whatever it may be, remain calm and sing Tukaram's abhangas .

Blessings from BAPU

From a photostat of the Hindi: G.N. 10668.

Pyarelal Papers. Courtesy:Pyarelal.

SPEECH AT MEETING IN WAI

I co-operated for 30 years but, today, I have embarked upon non-co-operation. Why? Only because, as our Shastras say, we may co- operate with a man while there is some little measure of goodness in him, but when a man is obstinately determined to forget his humanity, it becomes everyone's duty to turn his back on such a one. Tukaram taught this same thing, that there can be no co-operation between a god and a monster, between Rama and Ravana. Rama and Lakshmana were mere boys, but they fought the ten-headed Ravana. This British Government of ours has thrust a sharp dagger into the Muslims' heart, has slighted Islam. Cruel things have been done to men and women and to students in the Punjab. To prevent things from happening again, non-co-operation with the Government is the only way.

MY NOTES PILGRIMAGE TO MAHARASHTRA

A visit to the province in which Lokamanya Tilak Maharaj was born, the province which has produced heroes in the modern age, which gave Shivaji and in which Tukaram flourished, is for me nothing less than a pilgrimage. . I have always believed that Maharashtra, if it wills, can do anything.

SPEECH TO HARIJANS

The Gita is one of the greatest scriptures, if not the greatest of all. A religion which has given such a treatise and which has produced great saints like Jnaneshwar and Tukaram is certainly not destined to perish. We must realize that it is meant to live for ever, that is imperishable. Few of us here may know the name of Tiruvalluvar. People in the North are innocent even of the great saint's name. Few saints have given us treasures of knowledge contained in pithy epigrams as he has done. In this context, I can at this moment recall the name only of Tukaram.

WHERE IS THE LIVING GOD?

The following is taken from a letter from Bengal.

Fortunately the vast majority of people do have a living faith in a living God. They cannot, will not, argue about it. For them "it is". Are all the scriptures of the world old women's tales of superstition? Is the testimony of the rishis, the prophets, to be rejected? Is the testimony of Tukaram, Jnanadev, Nanak, Kabir of no value?

With the growth of village mentality the leaders will find it necessary to tour in the villages and establish a living touch with them. Moreover, the companionship of the great and the good is available to all through the works of saints like Kabir, Nanak, Dadu, Tukaram, Tiruvalluvar, and others too numerous to mention though equally known and pious. The difficulty is to get the mind tuned to the reception of permanent values. If it is modern thought-political, social, economical, scientific-that is meant, it is possible to procure literature that will satisfy curiosity. I admit, however, that one does not find such as easily as one finds religious literature. Saints wrote and spoke for the masses. The vogue for translating modern thought to the masses in an acceptable manner has not yet quite set in. But it must come in time. I would, therefore, advise young men like my correspondent not to give in but persist in their effort and by their presence make the villages more livable and lovable.

SPEECH AT PRAYER MEETING February 11, 1942.

We wondered where we should perform the cremation rites-at the Sevagram hillock, the public cremation ground or Gopuri. And it was decided to perform the rites at Gopuri where Jamnalalji had finally settled and for which work he had finally dedicated himself by renouncing his all. I was neutral in the matter but I welcomed the decision. Thousands of people converged on Gopuri to bid farewell to the body. After the cremation I asked Vinoba to recite an abhanga. He recited one from Tukaram. Lastly I requested him to sing 'Vaishnavajana'. He then sang this bhajan too.

SPEECH AT PRAYER MEETING , NEW DELHI,

Commenting on the Marathi bhajan sung by Shri Balasaheb Kher, the Premier of Bombay, Gandhiji said that like Shri Thakkar Bapa, Kher Saheb had been a servant of the Harijans and Adivasis ever since he had known him. Now he had put on the crown of thorns and become the Premier of Bombay. For Gandhiji his service to Harijans and Adivasis was more important than anything else. In the bhajan Tukaram makes the devotee say that he would prefer blindness to vision which could enable him to harbour evil thoughts. Similarly, he would prefer deafness to hearing evil speech. He liked only one thing, namely, the name of God.

The Hindustan Times, 23-10-1946.

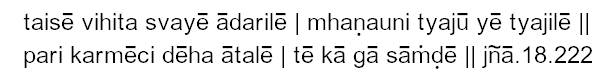

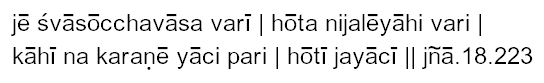

Translations of Tukaram

Mahatma Gandhi

Translations of Tukaram were done by Mahatma Gandhi in Yerwada Central Jail between 15-10-1930 to 28-10-1930.

1.Je ka ranjale ganjale

Know him to be a true man who takes to his bosom those who are in distress. Know that God resides in the heart of such a one. His heart is saturated with gentleness through and through. He receives as his only those who are forsaken. He bestows on his man servants and maid servants the same affection he shows to his children. Tukaram says: What need is there to describe him further? He is the very incarnation of divinity.

15-10-1930

2.Papachi vasana nako davoo dola

O God, let me not be witness to desire for sin, better make me blind; let me not hear ill of anyone, better make me deaf; let not a sinful word escape my lips, better make me dumb; let me not lust after another's wife, better that I disappear from this earth. Tuka says: I am tired of everything worldly, Thee alone I like, O Gopal.

16-10-1930

3. Pavitra te kul paawan to desh jethe Hariche daas janma gheti

Blessed is that family and that country where servants of God take birth. God becomes their work and their religion. The three worlds become holy through them. Tell me who have become purified through pride of birth? The Puranas have testified like bards without reserve that those called untouchables have attained salvation through devotion to God. Tuladhar, the Vaishya, Gora, the potter, Rohidas, a tanner, Kabir, a Momin, Latif, a Muslim, Sena, a barber, and Vishnudas, Kanhopatra, Dadu, a carder, all become one at the feet of God in the company of hymn singers. Chokhamela and Banka, both Mahars by birth, became one with God. Oh, how great was the devotion of Jani the servant girl of Namdev! Pandharinath (God) dined with her. Meral Janak's family no one knows, yet who can do justice to his greatness? For the servant of God there is no caste, no varna, so say the Vedic sages. Tuka says: I cannot count the degraded.

4. Jethe jato tethe tu maajha saangaati

Wherever I go, Thou art my companion. Having taken me by the hand Thou movest me. I go alone depending solely on Thee. Thou bearest too my burdens. If I am likely to say anything foolish, Thou makest it right. Thou hast removed my bashfulness and madest me self-confident, O Lord. All the people have become my guards, relatives and bosom friends. Tuka says: I now conduct myself without any care. I have attained divine peace within and without.

22-10-1930

5.Na kalataa kaay

When one does not know, what is one to do so as to have devotion to Thy sacred feet? When will it so happen that Thou wilt come and settle in my heart? O God, when wilt Thou so ordain that I may meditate on Thee with a true heart? Remove Thou my untruth and, O Truth, come and dwell Thou in my heart. Tuka says: O Panduranga, do Thou protect by Thy power sinners like me.

6. Muktipang naahi vishnuchiyadaasaa

To the servants of Vishnu there is no yearning even for salvation; they do not want to know what the wheel of birth and death is like.; Govind sits steadily settled in their hearts; for them the beginning and the end are the same. They make over happiness and misery to God and themselves remain untouched by them, the auspicious songs sing of them; their strength and their intellect are dedicated to benevolent uses; their hearts contain gentleness; they are full of mercy even like God; they know no distinction between theirs and others'. Tuka says: They are even like unto God and Vaikuntha is where they live.

23-10-1930

7. Kaay vaanu aata

How now shall I describe (the praises of the good); my speech is not enough (for the purpose). I therefore put my head at their feet.The magnet leaves its greatness and does not know that it may not touch iron. Even so good men's powers are for the benefit of the world. They afflict the body for the service of others. Mercy towards all is the stock-in-trade of the good. They have no attachment for their own bodies. Tuka says: Others' happiness is their happiness; nectar drops from their lips.

8.Naahi santpan milat haati

Saintliness is not to be purchased in shops nor is it to be had for wandering nor in cupboards nor in deserts nor in forests. It is not obtainable for a heap of riches. It is not in the heavens above nor in the entrails of the earth below. Tuka says: It is a life's bargain and if you will not give your life to possess it better be silent.

24-10-1930

9.Bhakt aise jaana je dehi udaas

He is a devotee who is indifferent about body, who has killed all desire, whose one object in life is (to find) Narayana, whom wealth or company or even parents will not distract, for whom whether in front or behind there is only God in difficulty, who will not allow any difficulty to cross his purpose. Tuka says: Truth guides such men in all their doings.

10. Ved anant bolilaa

The essence of the endless Vedas is this: Seek the shelter of God and repeat His name with all thy heart. The result of the cogitations of all the Shastras is also the same; Tuka says: The burden of the eighteen Puranas is also identical.

25-10-1930

11. Aanik dusre naahi maj aata

This heart of mine is determined that for me now there is nothing else; I meditate on Panduranga, I think of Panduranga, I see Panduranga whether awake or dreaming. All the organs are so attuned that I have no other desire left. Tuka says: My eyes have recognized that image standing on that brick transfixed in meditation unmoved by anything.

12.Na milo khavaya na vadho santan

What though I get nothing to eat and have no progeny? It is enough for me that Narayana's grace descends upon me. My speech gives me that advice and says likewise to the other people -Let the body suffer, let adversity befall one, enough that Narayana is enthroned in my heart. Tuka says: All the above things are fleeting;my welfare consists in always remembering Gopal.

26-10-1930

13. Maharasi shive kope to Brahman navhe

He who becomes enraged at the touch of a Mahar is no Brahmin. There is no penance for him even by giving his life. There is the taint of untouchability in him who will not touch a Chandal. Tuka says: A man becomes what he is continually thinking of.

27-10-1930

14. Punya parupkaar paap te par pidaa

Merit consists in doing good to others, sin in doing harm to others. There is no other pair comparable to this. Truth is the only religion (or freedom); untruth is bondage, there is no secret like this. God's name on one's lips is itself salvation, disregard (of the name) know to be perdition. Companionship of the good is the only heaven, studious indifference is hell. Tuka says: It is thus clear what is good and what is injurious, let people choose what they will.

15. Shevatchi vinanawani

This is my last prayer, O saintly people listen to it: O God, do not forget me; now what more need I say, Your holy feet know everything. Tuka says: I prostrate myself before Your feet, let the shadow of Your grace descend upon me.

16. Hechi daan de ga devaa

O God, grant only this boon. I may never forget Thee; and I shall prize it dearly. I desire neither salvation nor riches nor prosperity; give me always company of the good. Tuka says: On that condition Thou mayest send me to the earth again and again.

28-10-1930

In Light of India

Octavio Paz(1914-1998)

Octavio Paz was born in 1914 in Mexico City. On his father's side, his grandfather was a prominent liberal intellectual and one of the first authors to write a novel with an expressly Indian theme. Recipient of Nobel Prize for Literarture(1990), Paz was appointed Mexican ambassador to India in 1962 : an important moment in both the poet's life and work, as witnessed in various books written during his stay in India.

Paz was a poet and an essayist. His poetic corpus was nourished by

the belief that poetry constitutes "the secret religion of the modern age." Eliot Weinberger has written that, for Paz, "the revolution of the word is the revolution of the world, and that both cannot exist without the revolution of the body : life as art, a return to the mythic lost unity of thought and body, man and nature, I and the other." His is a poetry

written within the perpetual motion and transparencies of the eternal present tense.

Octavio Paz was born in 1914 in Mexico City. On his father's side, his grandfather was a prominent liberal intellectual and one of the first authors to write a novel with an expressly Indian theme. Recipient of Nobel Prize for Literarture(1990), Paz was appointed Mexican ambassador to India in 1962 : an important moment in both the poet's life and work, as witnessed in various books written during his stay in India.

Paz was a poet and an essayist. His poetic corpus was nourished by

the belief that poetry constitutes "the secret religion of the modern age." Eliot Weinberger has written that, for Paz, "the revolution of the word is the revolution of the world, and that both cannot exist without the revolution of the body : life as art, a return to the mythic lost unity of thought and body, man and nature, I and the other." His is a poetry

written within the perpetual motion and transparencies of the eternal present tense.

Excerpts from In Light of India

The philosophical antecedent of Sufism, its origin, is the Spaniard Ibn 'Arabi(1165-1240) who taught the union with God through all His creations. The affinities of Ibn 'Arabi with Neoplatonism are only one aspect of his powerful thought. Love opens the eyes to understanding, and the world of appearances i.e. this world is transformed into a world of apparitions; everything that we touch and see is divine. This synthesis of pantheism and monotheism, of belief in the divinity of the creation (the world) and belief in a creator God, was the basis, centuries later, of the thought of such great mystic poets of India as Tukaram and Kabir.

A revealing fact : all these mystic poets wrote and sang in the

vernacular languages, not in Sanskrit, Persian or Arabic. Tukaram(1609-1650), who wrote in Marathi, was a Hindu poet who was unafraid to refer to Islam in terms such as these: "The first among the great names is that of Allah....".But he immediately affirms his pantheism : "You are in the One.... In [the vision of the One] there is no I or you....". During the period of the decline of the Mughal Empire, from the beginning of the eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century, the coexistence of Hindus and Muslims had become a less a matter of entrenched opposition as it was under

Aurangzeb, but it never reached a state of reconciliation.

A revealing fact : all these mystic poets wrote and sang in the

vernacular languages, not in Sanskrit, Persian or Arabic. Tukaram(1609-1650), who wrote in Marathi, was a Hindu poet who was unafraid to refer to Islam in terms such as these: "The first among the great names is that of Allah....".But he immediately affirms his pantheism : "You are in the One.... In [the vision of the One] there is no I or you....". During the period of the decline of the Mughal Empire, from the beginning of the eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century, the coexistence of Hindus and Muslims had become a less a matter of entrenched opposition as it was under

Aurangzeb, but it never reached a state of reconciliation.

There were political and military pacts between Hindu and Muslim leaders, all of them provisional and dictated by circumstances; but there were no movements of religious or cultural fusion such as those under Akbar or, at the other extreme, of a Kabir or a Tukaram.

Missing for 350 Years, Retracing the Legend of Tukaram

Dilip Chitre

March 4,1999, is a very special day for all Marathi speakers. It is the 350th Tukaram Beej. The first Tukaram Beej was the second day of the lunar fortnight of the waning moon in the Hindu calendar in 1650 AD. On the forenoon of this day, the greatest Marathi poet ever, performed his last kirtan and simply vanished. The Varkaris who regularly go on a pilgrimage to the sacred town of Pandharpur to celebrate the biennial festivals of their parent deity Pandurang, - believe that at the climax of his last kirtan, Tukaram bodily ascended to Vaikunth (Vishnu’s heavenly abode).

Cinematic Classic

There are alternative hypotheses about Tukaram’s disappearance. One of them is that by some supernatural, paranormal force, Tukaram’s physical presence just disintegrated, even as his fading voice kept ringing in the ears of rapt audience. This by no means is a rationally convincing explanation. It only shifts the miracle from the realm of divine to that of the occult.

As a contemporary English translator of Tukaram’s poetry and as a Marathi critic interpreter of the great poet, I have faced this mystery in my book Punha Tukaram (Once More Tukaram; Pune, 1900;Mumbai, 1995). My answer follows my deconstruction of a group of poems by Tukaram that I read as the poet’s farewell to his friends and followers that may have been part of the text of his last kirtan. I imagine Tukaram leaving his audience rapturously singing the refrain of his last abhang or perhaps the Varkari chant Jai,Jai,Rama-Krishna-Hari or Pundalika Varada Hari Vithala. He had already told them in both literal and metamorphical terms that he was leaving worldly life for his final destination and that he had company ‘upto Varanasi’.

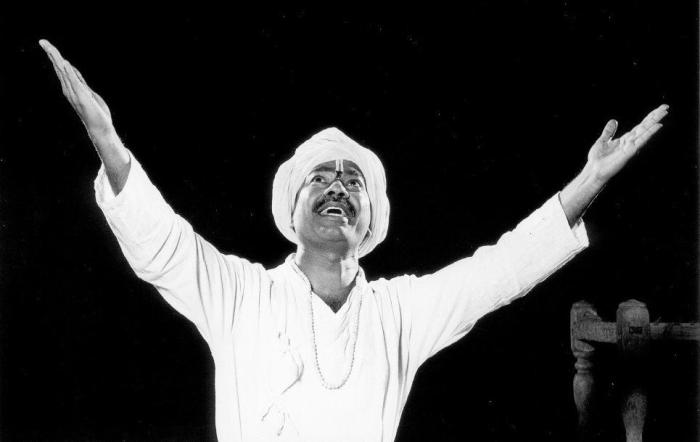

In the 1937 cinematic classic Sant Tukaram that was adjudged one of the three best films in the world made that year, the very final scene in the great mythical eagle Garuda , Lord Vishnu’s personal vehicle ,descending towards the bank of the river Indrayani at Dehu, Tukaram’s native village, flapping its powerful wings. In their time, the duo of directors at Pune’s Prabhat Studio - Vishnupant Damle and S. Fatttehlal- were the Indian film industry’s equivalent of George Lucas and Speilberg. The trick photography scene of Tukaram’s ascension to Vaikunth even by its naiveté appeals to western cinema buffs. I had the privilege of presenting Sant Tukaram to a German group of film enthusiasts in Berlin in the spring of 1992.They were moved by the authentic folk-tradition transformed into an absorbing work of cinematic art. There was applause for the late duo of directors at the end of screenings.

The debate of Tukaram’s intriguing disappearance 349 years ago has taken an unfortunate sensational twist in this, his 350th anniversary year, thanks to a new film based on scholar A.H.Salunkhe’s recent book Vidrohi Tukaram (Tukaram the Rebel) announced by Nilu Phule. Nilu Phule is unanimously acknowledged as an outstanding stage and screen actor and a director with a ‘purposive agenda’. Salunkhe’s book revives a 50 year old sensational hypothesis that Tukaram was assassinated by his Brahmin detractors who themselves spread the canard about his bodily ascension to Vaikunth as a cover-up operation. This is not really a hypothesis for it is simply not verifiable. For that matter, every explanation of Tukaram’s disappearance, including my own, is beyond testing. There is no contemporary eyewitness account of this event.

Murder ‘Theory’

The murder ‘theory’ may make a very dramatic script. Many screenwriters love this kind of stuff, especially about a historical figure who has become an icon for his cultural descendants. Just as a scoop is dream stuff for a journalist looking for a short cut to the top, to a filmmaker such controversial material is a box-office bet worth taking. However I do not think Phule is the kind of filmmaker to whom financial success is welcome at any cost. As for Salukhe I have no intention of casting aspersions on his intentions either. However, I am tempted to examine his logic and would love to shred it to pieces. But that job has already been done, and brilliantly too, by a direct descendant of Tukaram himself - Dr. Sadanand More, this year’s Sahitya Akademi Award winning Marathi author. Incidentally, the book for which Dr. More won the award is Tukaram Darshan gives a comprehensive historical review of how Maharashtra has received Tukaram so far. It uses Tukaram as a mirror of Marathi culture and society .

Dr. More has published a very comprehensive refutation of the theory of Tukaram’s murder by Brahmins in an article carried by Maharashtra Times ( 28th February, Sunday). He has rightly pointed out how this theory would hurt the feelings of devout Varkaris. However, it must be said to the credit of Varkaris that they are liberal enough not to ask for a ban on what they do not agree with. This is unlike the Mahanubhavs, another Hindu religious sect, which has succeeded in getting banned the late V. B. Kolte’s critically researched and comprehensively annotated edition of the 13th century classic of Marathi prose Lilacharitra. So I consider it extremely unlikely that Varkaris will react to any depiction of Tukaram’s murder by Brahmins the way Ayatollah Khomeini did to Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses.

Saintly Person

The Varkaris are mild and tolerant and there is ample textual evidence to show that Salunkhe’s Tukaram the Rebel was no one-dimensional social reformer or rabble-rousing critic of the Brahmins as a caste. Tukaram transcended communalism to include even Muslims among Vaishnavas and Sants and he wrote poetry in Dakhani Urdu in which Allah replaces his beloved deity, Pandurang. It is difficult to visualize such a saintly person hating an entire caste or community for any reasons. As Dr. More points out, half of the famous 14 accompanists of Tukaram in his legendary kirtan performances were themselves Brahmin. Tukaram’s most famous disciple was the poetess Bahinabai; and she, too, was a Brahmin.

The fact of the matter is: Tukaram’s poetry is as great a miracle as his life and his deeds that have now become part of the living folk tradition whose hidden significance has often eluded scholars and historians, literary critics as well as cultural commentators. He is quite simply the greatest missing person in the history of Marathi literature.

The Times Of India, Mumbai. 5th March (Friday), 1999.

Earth and Bhakti

Dilip Chitre

“You cannot split the Earth by drawing boundaries on it.” - Tukaram

1. We live on a planet that supports life and look for other planets that support life, anywhere in reachable space, in imaginable terms. We try to imagine another Earth and another mirror of life. For, supporting our life, the Earth becomes the very foundation of our awareness, the source of our being.

2. Our knowledge of ourselves cannot surpass our knowledge of the Earth, of which we are a mere detail. Richly detailed by life, the Earth may be conceived as an evolving art form and this, I suppose, is Tukaram’s perception. However interconnected above or beyond the Earth, all the forms of life that spring from the Earth share it as their origin and their heritage.

3. James Lovelock’s famous and controversial Gaia Hypothesis has now been around for more than four decades. Simply stated, it proposes that the Earth is alive. Lovelock being an atmospheric chemist---and not a poet, an artist, a mystic, or a philosopher---his hypothesis could not go unnoticed by his scientist colleagues. As in every field of human endeavour, in science too there is a powerful orthodoxy that attempts to control its own domain from what seems heretical and politically dangerous. Once upon a time, the Church controlled science. The position was nearly reversed in a matter of just three centuries. Today, scientists call their colleagues who challenge the status quo heretics much in the same way the Church once did.

4. Tukaram was a 17th century Marathi poet and arguably the greatest poet in the tradition of Marathi Bhakti poetry founded in the philosophy of the 13th century poet and thinker Jnandev. As a modern translator of Tukaram and other Marathi poet-bhaktas, I have come to believe that their world-view is relevant to our own time as well, and in large measure this is because their faith is rooted in the Earth as a spiritual entity.

5. The Varkaris are pilgrims vowed to visiting the sacred city of Pandharpur on fixed days in the Hindu lunar calendar: the eleventh day of the bright fortnight in the months of Ashadh and Kartik are the days on which they visit the temple of Vitthal or Pandurang, their deip. It is on this day that Vitthal, leaving his legendary abode in Vaikuntha (the residence of Lord Vishnu), visited Pandharpur to meet Pundalik, his devotee; and dazzled by the devotion of Pundalik to his this-worldly obligations, decided to stay on in Pandharpur forever. The story is that when Pandurang came to Pundalik’s door, the latter was engaged in massaging the feet of his aged parents. He motioned Pandurang to stand on a ‘brick’---a stone slab really---while he finished serving his parents. The priority Pundalik gave his parents over his deity impressed Pandurang, the deity. The devotion or ‘bhakti’ of Pundalik becomes the symbol of ‘earthly engagement’ for the Varkari. It is the cornerstone of his faith in human life and its eternal cycle of sowing seeds, raising a crop, harvesting the crop, and thanking the Lord for governing this entire process. The Varkari is the farmer worshipping the Earth. He seeks the blessing of Pandurang in Ashadh, when the monsoon rains arrive, for a bountiful crop; and in the autumn month of Kartik he thanks his Lord.This is the earthly version of the cosmic and cyclic process of creation, preservation, and dissolution. It is the expression of faith in life and its meaning in folk terms.

6. The Vari or the periodic pilgrimage to Pandharpur---is a living tradition of Maharashtra. About half-a-million people participate in it. A unique feature of this pilgrimage is taking the palanquins of ‘sants’ or great devotees of Pandurang to Pandharpur. The youngest son of Tukaram, Narayan, who was born after his father had passed away, started this practice. Narayan placed the sandals (paduka) of his father and carried them from Dehu, his native village, to Pandharpur.Narayan was thoughtful enough to carry the symbolic sandals of Jnandev from Alandi in the same palanquin. As they march on foot to Pandharpur, Varkaris chant “Gyanba-Tukaram” or “Jnandev-Tukaram” all the way, as though they were physically carrying their beloved saints to Pandharpur with them. Today, the palanquin of Jnandev leaving from Alandi and the palanquin leaving from Dehu are separate. But “Gyanba-Tukaram” remains the common and universal Varkari chant.

7. Although all Varkari poet-Bhaktas sing songs that praise the Lord--- Vitthal/Pandurang ---and visualise Him as Vishnu or Krishna in their act of poetic remembrance and verbal expression, their deity dwells only metaphorically in Vaikunth or ‘heaven’. Pandurang, for them, is the cosmic spirit that is present simultaneously within all space and time, and also beyond. He is both Vishnu and Shiva and, according to Jnanadev, the two forms cohere just as Shiva and Shakti cohere to create a cosmic creative resonance. In his interpretation of Shaivism, Shiva or Absolute Being and Shakti, the curiosity, capacity, and will to create many forms to express oneself are indivisible or Advaya. The phenomenal world is not unreal just because it changes; it is not Maya or illusion. It is real. Change is reality, though temporal. It is the expression of the creative, dynamic spirit of the Creator. Since human awareness of existence in relation to the constant spirit of the Creator reflected in changing forms to express its creativity, the Creator within every human bhakta shares the spirit of God. The Bhakta is the Shakti of God reflected in a finite form, an earth-bound creature resonating with the cosmic spirit. God may be in heaven, but His feet are rooted in the Earth at Pandharpur where, as Vitthal, he dwells waiting for His Bhaktas ever since the bhakti of Pundalik entranced Him.

8. For the last eight centuries or more, Varkaris have greeted heaven’s descent on Earth in the form of the arrival of the monsoon to renew the life-cycle of the Earth. At the beginning of the sowing and planting season, they make a pilgrimage to Pandharpur, the earthly dwelling-place of the Cosmic Parents---the male-female spirit of the universe. After reaping their harvest, they return to Pandharpur to celebrate it.

They find their God in the Earth and its ecology and their faith in the coherence of the cosmic spirit in its resonant relationship with life on the Earth.

The Revolt of the Underprivileged

Part - I

Style in the Expression of the Warkari Movement in Maharashtra

BHALCHANDRA NEMADE

Bhalachandra Nemade, a leading Marathi novelist, poet and literary critic, was born in the Maharashtra village of Sangavi in 1938. With a Ph. D. and D. Litt. from the North Maharashtra University, he taught in many places retiring from Gurudev Tagore Chair of Comparative Literature at the University of Mumbai.

His first novel, Kosala, established the modernist trend in Marathi literature and is considered a modern classic. This was followed by other novels and poetry, which gave him eminence among contemporary Marathi writers. Tikasvayavara, a highly acclaimed body of literary criticism, won him the Sahitya

Academy Award in 1990. His works display a deep understanding of Marathi culture and depict the indigenous lifestyle of the Maharashtra region.

His first novel, Kosala, established the modernist trend in Marathi literature and is considered a modern classic. This was followed by other novels and poetry, which gave him eminence among contemporary Marathi writers. Tikasvayavara, a highly acclaimed body of literary criticism, won him the Sahitya

Academy Award in 1990. His works display a deep understanding of Marathi culture and depict the indigenous lifestyle of the Maharashtra region.

I

If we may assume that the bhakti movement is the most significant creative upsurge of the Indian mind during the present millennium , no student of literary culture can ignore the unique techniques of expression developed within the Warkari Movement in Maharashtra .The creative influence of this movement has been felt in a variety of forms by several social and political revolts in the Indian subcontinent from Shivaji's rebellion in the seventeenth century to Gandhi's in the twentieth .In Maharashtra , to which the present study is confined , the movement has an unbroken tradition which can be traced back to the thirteenth century on the eve of the Muslim invasion of the kingdom of Deogiri. Throughout these centuries there has hardly been a period of any considerable length when the Marathi - speaking people of India can be said to have enjoyed peace and prosperity .Until the rise of the Maratha kingdom in the middle of the seventeenth century , society passed through '' trying times '' under often fanatical Muslim governments . That the Warkari movement , mostly led and sustained by the underprivileged classes should arise in this time of national catastrophe and , despite hostile conditions , develop quietly into the most influential mass movement of rural Maharashtra , is the triumphant result of the broad - based , autonomous and unique style that it generated within itself .

Perhaps a brief comparison with another major movement , that of the Mahanubhavas , which was influential predominantly in thirteenth century Maharashtra , would make the unique stylistic contribution of the Warkaris more clear . The Mahanubhava movement(1) was a Hindu monastic cult founded by Chakradhar (1194 - 1276 ) and it too was supported by the underprivileged classes , although their leaders were mainly learned Brahmans . The cult preached radical values laid down by Chakradhar principally equality and brotherhood . It disregarded the Vedas , attacked Brahmanism , worshipped only one God Krishna and prohibited worship of any other god , and offered equal status to women and shudras .After Chakradhar was killed in 1276 as a result of the hatred he had aroused in the arrogant supporters of Brahman orthodoxy , the Mahanubhavas , unlike the Warkaris , failed to improve upon their techniques of expression in order to cope with the changing political situation .For example , their tendency to favour written as against oral culture increase their dependence on bookish philosophy and textual criticism .Their wearing of conspicuous black dress and their secretive monastic activities alienated them from the common people .Their leadership , unlike that of the Warkaris , came from the top instead of from the grass roots .Their monastic establishments , free association with women and shudras ,their anti - Brahman philosophy and adoption out of fear of several esoteric scripts - all these characteristics made them ineffective in the successive waves of fanaticism and orthodoxy .Soon , therefore , this cult which once was so influential , so revolutionary and so creative in its literature , turned into a pale reflection of itself and by the end of the sixteenth century it had become an object of ridicule within Maharashtra at large .The Mahanubhavas prose works which were created in the thirteenth century have great stylistic merit , but being written they soon became obsolete until in the twentieth century the cult began to show signs of revival .

The Revolt of the Underprivileged

Part - II

Work in progess.

Tukaram’s Poetry

J.R.Ajgaonkar

No one to this day has satisfactorily solved all the questions that crop up in regard to Tukaram’s poetry- questions, for instance, as to what was the total number of Abhangs that he wrote, how many of them are available at present, whether some of the Abhangs that bear the name of Tuka are not really the work of some other person of that name, and so on.

Most biographers seem to believe that the four thousand and a half Abhangs that are found published in a volume called the ‘Traditional Collection’ are all that Tukaram ever wrote, and that everything else must be taken to be spurious! Evidently it has never struck these people that a rapid versifier who could even talk in verse at all times of the day, could have produced no more than such a small quantity during his long career of thirty to forty years. Of course, if all the manuscripts, whether written by Tukaram himself or by his disciples during his life-time, were available today, the question about the quantity would never arise at all. But even as it is, what we know already about Tukaram’s compositions is enough to prove that he must have composed more Abhangs than are to be found in the ‘Traditional Collection’. One of the fourteen cymbal-players of Tukaram, Santaji Teli Jagnade, wrote down several Abhangs of Tukaram; these have been preserved by Santaji’s descendants; and out of them, 1,200 were published without the slightest change, in book form, by the late Mr. V. L. Bhave. These latter contain a large number which are not to be found in the ‘Traditional Collection’ at all! This in itself is sufficient to indicate that Tukaram must have composed a great deal more than four thousand and a half Abhangs.

In 1889 A.D. the late Mr. Tukaram Tatya Padwal, having, with the most commendable zeal and devotion instituted a search from village to village, published a volume containing 8,441 Abhangs, i.e. about four thousand more than those given in the ‘Traditional Collection’, bearing the name ‘Tuka’. Not all of these new ones, however, belong to Tukaram proper, a remark that is equally true of the old collection, for there were other ‘Tukas’ such as Tuka Brahmanand of Satara, a contemporary of the great saint. Again some of the Abhangs, wrongly supposed to bear the name ‘Tuka’ really bear the expression ‘Tukaya Bandhu’, meaning ‘Tuka’s Brother’, a title used for his own Abhangs by the great Tukaram’s brother Kanhoba. In spite of this, however, there still remain hundreds of genuine Abhangs of Tukaram, scattered all over Maharashtra waiting to see the light of day.

The present form of the language of Tukaram’s poetry does not appear to be the original one. The form of the language therein differs considerably from that of the Abhangs printed in the traditional collection, but is the same as that found in the manuscripts written by Tukaram’s cymbal-player Santaji Teli Jagnade. In this original form, the words are not split up, but run into each other; the dental ‘I’ appears through out as lingual ‘I’. The end of the Abhang quarter is marked not by a vertical line, but by a couple of vertical, dots; and finally, not much attention is given to the distinction of short and long vowels. In short, Tukaram himself wrote in his rustic fashion, but, later on Rameshwar Bhatt or some other disciple of Tukaram must have given it the form that is found in the ‘traditional collection’.

The popularity of Tukaram’s poetry has never abated in the least to this day, no bhajan possible without it, and there can be no kirtan but must begin with it and end with it-with the Abhang “Grant just this, 0 Lord !”.Several lines of his have become household words! No other Marathi poet, medieval or modern, has ever had such universal allegiance. Even the British Government in India did him the unique honour of publishing his works officially. The Bombay Government more than sixty years ago, spent Rs. 24,000 in getting a compilation of Tukaram’s Abhangs edited by the Late Mr. Shankar Pandurang Pandit. This was the first authoritative collection of Tukaram’s Abhangs. Before that, the late Mr. Madhav Chandroba Dukle had a considerable number of them lithographed and published through his periodical Sarva-Sangraha(‘the All embracing Collection’).

Since the Government compilation, there have appeared about twenty-five editions of Tukaram’s Abhangs during the last sixty years published by various publishers, the total number of their copies amounting to well-nigh a hundred thousand. Most of these, however, are mere reprints of other collections. The late Mr. Fraser of the Indian Education Department, and the late Mr. Marathe .of the Bombay Judicial Service jointly published an English translation of a number of Abhangs through the Christian Literature Society. A few Abhangs have been rendered into modern Marathi prose by the ‘Tukaram Society’ of Poona. The late Vishnu-buwa Jog of Poona, at prominent Varkari, published a collection also, with a modern Marathi prose rendering. ‘A necklace of the Abhang jewels of Tukaram’ by the late Mr. Shantaram Anant Desai, Professor of Philosophy at the Holkar College, lndore, deserves perusal. An excellent essay, not now available, was written by the late Mr. Balkrishna Malhar Hans, a man of great critical acumen. The late Mr. D. G. Vaidya, Editor of the Prarthana Samaj’s official weekly organ Subodh Patrika, used to publish in that paper, from time to time, a fine dissertation on some of the Abhangs. These dissertations he afterwards collected and reprinted in the volume of his writings published a few years ago.

To review and assess the worth of the poetry of Tukaram would be the height of presumption for any but his compeers like Jnanadev, Namdev, Ekanath, and other saints. The poetry having bubbled forth from the deepest recesses of the saint’s heart cannot be easily valued by an ordinary mortal. The saint’s expression of his ideas is unsparingly outspoken, yet overflowing with love. One critic may regard the language used in certain places as ‘harsh’, another may point to his outspokenness in certain places as ‘indecent’, a third may object that certain words he has used are ‘vulgar’. But these critics must never lose sight of the all-important fact that the mental attitude of the saint in respect of every single word uttered or written by him was one that was described in the words:

“Drowning themselves are these folk - I cannot bear the sight!”

Just as a father, in his anxiety for the welfare of his son, would cajole or threaten or even beat him on occasions, all with a view to bringing him to his senses, even so Tukaram, with his heart pining for the welfare of humanity, used different language to suit different situations, all with a view to bringing mankind to its senses. True it is that on occasions he has made use of some ‘vulgar’ words, but that is partly because he was living in a village and his language is a reflection of the village life of his day. When even such, avowed scholar-poets as Mukteshwar, Vaman and Moropant could not avoid an occasional use of an indecent word, what wonder if Tukaram used a few? “In the heat of sermonizing,” says the late Mr. N. C. Kelkar, in his critical essay on ‘The Problem of Obscene Literature’, “when the preacher forgets himself in his talk, it is possible that the excited state of his mind may let slip an unapproved or jarring word from his lips; but the sense of sacredness there, both of the man and his subject, is so strong that it completely overpowers the sentiment of indecency! But the preacher can have this benefit only in proportion to his status”. Tukaram’s spiritual status was undoubtedly high; so the sentiment of obscenity was entirely absent.

As literature, Tukaram’s poetry is wholly spiritual and introspective and can well be compared and contrasted with the poetry it bears the closest resemblance. The poetical merit of Jnanadev’s work, especially in respect of the Jnaneshwari, is very high, its language also is highly ‘urbane’, that is to say, courteous and elegant. Even when he wants to thrash, Jnanadev does so with a silken string of delicate words, so that the lashes, far from causing smarting pain, only produce a tickling sensation. Not so Tukaram. He has, as it were, a leather strap ready to lay on the backs of people. This difference was natural in away, for while Jnanadev was primarily an author, Tukaram was an out and out preacher, admonishing people face to face! The case of Ekanath was rather different. He was both an author and a preacher, and his language in his moral poems is not as gentle as in his other works. Tukaram’s poetry, however, has one important peculiarity : when it comes to the invoking of Shri Pandurang, its harshness disappears, and it is all a smooth-flowing stream of sweetness and love! Tukaram, on occasions, did not dare to ‘quarrel’ with Pandurang Himself, but the words that he uses there are so ingenious that they were calculated to provoke in the Deity not anger but only a smile! Tukaram’s similes are very expressive and sweet. His language, though somewhat rustic, is both striking and effective. It is apparently very simple, but the meaning of some of the Abhangs is not easy to grasp. The variety of abhangs adds to the difficulty still further.

Tukaram firmly believed that his verse was not his own, that his mouth was merely a vehicle for Shri Pandurang’s utterance. He has expressed this sentiment in several of his Abhangs, but nowhere as beautifully as in the following:

The power of speech is not one’s own;

God’s the friend-the speech is His!

What is a maina to sing sweet tunes!

Else is the Master who makes it sing!

Who, poor me, to speak wise words?

It is that World’s supporter has made me speak.

Who, says Tuka, His art can guage?

He even makes the lame walk without legs!

Tukaram’s Abhangs, barring a few incidental ones, can be roughly classified under the following topics:-

1. The Puranas (Mythology);

2. Lives of Saints;

3. Panegyric of Shri Pandurang;

4. Laudatory description of Pandharpur;

5. Autobiography and self-scrutiny;

6. Moral instruction;

7. Personal explanation;

8. Miscellaneous;

9. In defence of his Religious Principles and

10. Bharud (Mixed).

Besides the Abhangs, Tukaram has a considerable quantity of other verse in a variety of forms, such as Shlok, Arati and Gaulani. He has some verse in Hindi also.

The essence of Tukaram’s teaching is “Repeat Hari’s Name”. Along with this, however, he gives an important warning that “Whosoever takes the matra (a strong medicine administered in minute particles) of Vithal, must observe the dietary”. And it is the dietary viz. good conduct, kindness to all living creatures, non-killing, beneficence, acknowledgment of Universal God, etc. that is all in all. Without that dietary the matra can never prove effective, warns Tukaram.

Tukaram lays great stress on pilgrimage to Pandharpur and worship of Pandurang, yet that is not the essence of his teaching. That essence is embodied in such Abhangs as

“(Realizing) the immanence of Vishnu is the religion of Vishnu’s devotees. ...”

“ The secret of the Almighty’s worship is not to bear ill-will towards any living being. ...”

“ The saint is he who befriends the wearied and oppressed: in the company of such saints God resides. ...”

“ Wherever dwells peace, God’s company is there. ...” etc.

His sense of oneness is not limited to mankind, but is wide enough to embrace the whole living and sentient world, as is evidenced by the use of the word ‘being’, instead of ‘man’ in the first of these Abhangs.

Though Tukaram was not a great scholar like Jnanadev, Ekanath, Vaman and others, his reading of books and observation of men and things was, for his time, considerable indeed, as shown by his writings. His formal education had never gone beyond reading and writing; yet, once his mind had turned towards spiritual life, he made large additions to his knowledge by reading several Marathi works on Puranas and philosophy, by getting a number of Sanskrit books explained to him, and by attending performances of kirtan and reading of Puranas. The Jnaneshwari and the Bhagwat of Ekanath formed the solid basis of his poetry. The profundity of his knowledge of the world and of human nature can easily be gauged from the hundreds of topics that he has dealt with, as occasion demanded, in his Abhangs. They give a good deal of information regarding the state of society, religion and country prevailing at the time.

Even as mere poetical compositions, his Abhangs rank high. He never made any conscious attempt at composing in strict conformity with the canons of the science of poetics. But his feelings were so powerful that verses composed by him under their influence would automatically become the highest kind of genuine poetry.

Anandowari Revisited

G. P. Deshpande

G. P. Deshpande, Marathi playwright, was born in 1938 in Nasik, Maharashtra. He received the Maharashtra State Award for his collective work in 1977, and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for playwriting in 1996. Prof. Deshpande is known for advocating strong, progressive values not only through

his academic writings but also through his creative work. His plays especially reflect upon the decline of progressive values in contemporary life.

Having specialized in Chinese studies, he was head of the the Centre of East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. The Library of Congress has acquired twelve

of his books including a few on Chinese foreign policy. Some of his works have been translated into English.

his academic writings but also through his creative work. His plays especially reflect upon the decline of progressive values in contemporary life.

Having specialized in Chinese studies, he was head of the the Centre of East Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. The Library of Congress has acquired twelve

of his books including a few on Chinese foreign policy. Some of his works have been translated into English.

Anandowari Revisited

In a remarkable piece of polemic Maharshi Viththal Ramji Shinde (1873-1944), an early twentieth century thinker and political and social activist, summed up the state of Marathi letters thus : Marathi language (and literature) was alive (and prosperous) from Jnandadev (1275-1296) to Tukaram (1609-1650). (From the 13th to the 17th century that is). He then went on to list the people responsible for its decline that followed. He has actually held them responsible for ‘strangling’ the Marathi language! His detailed list of culprits responsible for such a heinous act against the genuine creative urges of Marathi and of course, innocents among the Marathi authors is not important for our argument. The fact is that there was something that the colonial period did to our creativity which resulted into a crisis of the arts especially of literature. I do not think that it is in the main due to our moving away from nativism. More likely it was due to the general colonial tendency to trace the cultural crisis to our image of ourselves. The colonial logic generates an image of the conquered acceptable to the colonizers.

It is accepted wisdom that writing in Indian languages begins with poetry. Strangely Marathi is perhaps the only Indian language which can boast an antiquity for its prose writing that is as old as that of its poetry. The Mahanubhava prose writing dates back to the thirteenth century. Considered to be the first work in Marathi - Vivekasindhu (An ocean of thoughts) by Mukundaraj. But Mahanubhava writing is comparably ancient.

It is therefore not strange that Shinde, well versed in the literary tradition of Marathi took umbrage at the scant regard that the “modern” writing showed to this tradition or to its elegance and achievements. Small wonder then that Shinde rather ruthlessly attacked the literary mavericks as also the serious writers and nearly dismissed them from the hall of fame of the Marathi belle letters.

The pale romanticism that dominated the Marathi literature during the colonial period was made worse with the rise of a rather lifeless “new and standard” language during the colonial period. It was really in the post-independence period that the Marathi literature especially prose seemed to acquire a new life-line. The fifties through seventies of the last century suddenly saw a rise of newer and fresher forms of writing. Fiction came into its own. The famous and much celebrated authors of the new fiction were Gangadhar Gadgil (1923-2008), Arvind Gokhale (1919-1992) and others. At the same time traditional narrative forms also acquired a new strength and life. Vyankatesh Madgulkar (1927-2001) and Digamber Balkrishna Mokashi (1915-1981) were the principal exponents of the latter school. It is not modern or new in the sense Gadgil’s fiction was. It was in many ways an expression of modernized tradition. Its main thrust was to demonstrate that a simplified version of a movement from the dated and pre- industrial oriental tradition to a modernity of industrial and material world was the modern impulse. What authors like Mokashi and Madgulkar achieved was to rid the literary history of the linearity that the nineteenth century seemed to have straitjacketed it into.

Mokashi thus is a writer who along with Madgulkar gave a new lease of life to the world of Marathi letters. As quite often happens, Mokashi never got his due recognition. He remained an unsung hero of Marathi fiction His work Anand Owari is in many ways the statement of modernized tradition. This rendering of that work in dramatic mode is a tribute to Mokashi that has been due for a while. It is to be welcomed that the dramatic rendering is now available in a film. Vijay Tendulkar (1928-2008), easily the most celebrated of modern playwrights of India. He was also an admirer of Mokashi’s work. But that is not all. He has edited Mokashi’s work with a sensitivity that is new to Marathi literature.

The story that Mokashi narrates in this work is the quintessentially central point of debate in modern Marathi. What does one make of the Bhakti tradition of medieval literatures of India? Of course it has posed different problems in different language areas of India. In Marathi the debate has centred on the contradiction between Pravritti (initiative and action) and Nivritti (resignation and withdrawal) Mokashi in a sense relives that debate through Kanhoba, the younger brother of Tukaram, easily one of the greatest poets of Marathi ever. Kanhoba poses the tension between the mundane world of crass materiality and the spiritual or mystic renunciation of that world. Kanhoba emerges in this narrative Tukaram’s alter ego of sorts. In a sense this narrative rejects the modern day versions of the debate like the one of nationalist historian Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade (1863-1926) or a protagonist of the mystic (Mumukshu in Marathi) tradition like Laxman Ramchandra Pangarkar (1872 - 1941). This story establishes the dialectical nature of that engagement. Understandably the nationalist zeal of that debate can be easily dehistoricised and misunderstood today. Indeed that is happening today. But it appears that Mokashi’s Kanhoba is asking the same question more pointedly and poignantly.

Kishor Kadam as Kanhoba in the play Anand Owari

Like the questions of political power and its renunciation that Rajwade found relevant in his discussion of the Sant Kavis (the Bhakti poets of Marathi) Kanhoba in his grand soliloquy is posing the question if the materiality of the world and its mundane compulsion can be wished away at all. Kanhoba is caught in a trap of that mundane world and his beloved brother losing himself in his Bhakti and his Vithoba, the Lord standing akimbo at Pandharpur aptly described by Guy Deleury in his introduction to the French translation of selected poems of Tukaram ( Tukārāma: Psaumes du pèlerin [French] (UNESCO Collection of Representative Works) / Guy Deleury / Paris: Gallimard [France], 1956.), as the Jerusalem of the Marathas. Mokashi celebrates that.

Kanhoba lends poignancy to Mokashi’s work which sums up the dilemma that paradoxically has made Tukaram the most loved poet of Marathi. In the end there is no answer to Kanhoba’s predicament or the entanglement in the mundane world and the spiritual quest. He cannot resolve it the way his brother did or could. At times in Mokashi’s work, he seems to be uncertain if his brother really ever solved the dilemma. For Mokashi’s Kanhoba, the quest is not over nor is it ever likely to be over. His Parabrahma (supreme reality) is distinct and different from Tukaram’s.

Well, in short this is a major work and it should indeed be celebrated that at least an edited version is now available in English. For far too long has our discussion and appreciation of the Bhakti literature has got stuck in clichés. Kanhoba, Tukaram and Mokashi would get us out of the clichés. May be we shall discover the points of strength of modernized tradition and its literature. Let Anand Owari be a voyage of discovery of Kanhoba, and no less Mokashi.

Sant Tukaram ( The Movie ) Part I

Gayatri Chaterjee

Interestingly, the very beginning of the film seems to be fully employed in creating an ambience so the audience is immediately drawn. It is as if based on the assumption the audience is capable of being very still and attentive—meditative even The first segment is made up of three shots: i) a still shadowy silhouetted image of the actor, over which run the credit titles; ii) a full frontal shot of the deity Vitthala (or Panduranga, along with his consort Rakhumai) standing straight, looking into the camera as if it were; and iii) an image of Tukaram, sitting on the ground cross-legged, at a slight angle to the camera. These are iconic images—having past histories rooted in the cultural and pictorial history of Maharashtra. It is apt the film begins with iconic images. It is interesting that such iconic images have been produced by camera lens. These shots are of very long duration; particularly, the Tukaram image, which remains on the screen for over 2 minutes (206 feet).footnotes : [1] Normally, it is considered difficult to gaze at a static shot in a film for a great length of time—and here we have (after the credits) two static-shots where nothing moves within the image and the camera is static too (except for a slight track-in at the end of the first). But, we have no problem gazing at these images, as the images are accompanied by a song panduranga dhyani panduranga mani—an original abhang composed by the seventeenth century saint poet. Without the music it perhaps would have not been impossible to engage the interest of the audience for such a long time—even if they are habituated to gaze quietly at their favourite idols at home or in the temple. The real-life habit of gazing still and long at one’s adored God has been ‘borrowed’ here in this medium of cinema. There is no other instance of a film where this element is so well and persistently used. Interestingly, the verse underlines the above aspect of adoration and worship; Tukaram sings how he is engaged in dhyan (meditation) and manna (introspection). There is a reciprocal stance both the God and the devotee adopts and the term here is tatastha. Vitthala or Panduranga stands ramrod straight, arms akimbo placed on the hips.

This is a term used in the Natyashastras and it means: when one is looking at a performance one needs to be fully immersed in what is going on in front and at the same time one is sufficiently detached. Ashok Kelkar explains: tatastha is to stand by the bank (tata)footnotes : [2] of an ocean or a river—looking on, taking pleasure but not taking the plunge. It is as if, the verse signals our own stance for viewing this film—any film, for that matter—a stance of full absorption but ultimately analytical and objective. So, let us embark upon some deeper understanding of this ‘marriage’ between a former tradition and the new medium of cinema that is creates this tremendous possibility of appreciation here.

One etymological meaning of icon is ‘resemblance’. The image of Tukaram resembles our mental image of a sant. Though the identity of the man is not yet established, we immediately know him as a devotee or the principal protagonist whose name the film bears. We must ask, there must have been before this image a tradition of image of Tukaram—and there was. A litho print accompanied most books printed in the first decades of the previous century (and well into the forties and early fifties as well). It seems this image was the model before the silent film, Tukaram (1921) directed by Ganpat Shinde (but often attributed to D G. Phalke—perhaps Phalke was consulted).footnotes : [3] Importantly, Vishnupant Pagnis bears a striking resemblance to the actor of that film.footnotes : [4] Now, there was another film Sant Tukaram (attributed to the director Patankar) made the same year and we wonder what its actor Baba Vyas looked like. The actor of Rane’s Sant Tukaram aani Jai Hari Vitthala was Shukla, from the play by Rane. We need to carry out full research as to the acting and singing of these actors, if we want to fully understand our appreciation of the Damle-Fattelal film. But let us return to the fact that it begins with iconic image—those that only the moving image and the audio-visual juxtaposition of the medium of cinema can create.

An iconic image is where narration—story, information, and discourse—meaning and feeling rest frozen. Icons belong to specific traditions, and one must know the tradition in order to properly recognize and absorb the image. An icon stands for something known to the audience a priori. An icon is suspended in time—it is meant for us to gaze at, admire and contemplate upon. To use of iconic images in the beginning of a narration is in keeping with the literary practices of the period: to start novels with iconic figures—not exactly illustrations, but images that introduce or leads a reader to the world of narration and representation. Interestingly (but not surprisingly), we see the same phenomenon in the magic lantern shows called shambarik karolika in Maharashtra. Before the mechanism in the magic lantern moved its images, there would be first a still-image (the show ended too with some still-image). So traditionally, a still image moves and thereby initiates and sets loose the process of narration (discussion/discourse), as if it were; and with the end of narration, the image becomes still again—a tradition several Indian films have adopted and here it is carried out particularly well.

Next, we observe the first image of the God is placed in a full frontal manner (looking out straight in front), while in the second, Tukaram figure is positioned at a slight angle to the camera (or to our eyes). As a result of the two images coming one after the other (joined through the process of editing), they give rise to a triangular spatial arrangement. They create a space to be filled in or occupied by a third person—the audience then looks at the God, at the sant and their very special relationship. This too is a time worn convention in the Bhakti literature.footnotes : [5] A devotee forms and shares a closed world with an adored God; but when this relationship is narrated, sung or represented, there is a third—a spectator looking on at both. So, here is a cinematic creation of a traditional positioning of three characters in a triangular relationship: the bhagavān (the god), the bhakta (the devotee) and the audience.footnotes : [6]

The two shots are joined by the process of editing; the iconic images are created through the medium of cinema—mise en scene and editing. If the filmmakers had composed the two images in full frontal manner or followed the rules of eye-line matching of a classical shot counter-shot, that would have established the bhakta looking at the bhagavān. The camera would then take up each viewing position; the audience, in turn, would alternately take up the position of Tukaram and Vitthala. But that is not the case here.footnotes : [7] Additionally, the two shots are composed in different ways—the image of the God has no background, while that of the devotee is placed with recognisable objects of farm and home use. Which means Vitthala and Tukaram are not spatially connected—but connected through our relationship with them.

[1] What is highly interested here is: we say this is coming from a religious-performative tradition; but let us note that such uses of long held immobile or static shots are used in very avant garde European films.

[2] The first ‘t’ is dental, while the second one is formed when the tongue hits the palate.

[3] It is quite possible that our filmmakers had seen the film made by/under the supervision of Phalke. The personnel of Prabhat Studio knew Phalke very well Phalke had visited Maharashtra Film Company, when he was still an established filmmaker. The Prabhat personnel had donated to the fund being raised to help Phalke as they celebrated 25 years of cinema (Phalke was in a state of penury then). A. V. Damle (dada-Damle to us) informed me of these events (also mentioned in Film India).

[4] One real of that film is preserved in the National Film Archive of India; but the name of the actor is not known today.

[5] Norman Culter has excellently discussed this in his book on Tamil Bhakti poetry, The Song of the Road.

[6] Perhaps this had already become quite an established practice in the Indian studios by the 30’s; an exact recreation of this triangularity occurs in Vidyapati of the New Theatres made in 1936.

[7] The directors, I suggest did not want the audience to take up the position of the God.

Sant Tukaram ( The Movie ) Part II

Gayatri Chaterjee

There is another triptych in this tradition is: bhagavan, bhakta and pad (here abhang). The song is background music for the title-card and for the shot with the image of the God. In the third, the sant sings the song (in lip-synch-Pagnis sings his own song). The abhang (known to several members of the audience) also iconic does not begin the story, only creates an ambience and situates the audience in the tradition within which the story is to unfold.

The song is continued in the voice of the next character, Salomalo, but now sung differently. Music director Keshavrao Bhole has described how he borrowed from the Sangeet natak mode and created for him a dramatic, ornamental but show-offish style of singing. Here the iconic element is totally broken. The camera begins to move; the scene has many characters; the process of editing bring in several shots; and there is also dialogue inserted and added on to the singing. Bhole had written: the story begins with Salomalo-the false devotee. In dramatic terms, Salomalo is the villain; in terms of the tradition of Bhakti, he is the agent positioned in the narrative to provide obstacles in the path of the bhakta. In episode after episode, he will do this: he will bar Tukaram’s entry into the temple; send the local prostitute Sundara to lure Tukaram astray; invite the Brahmin Ram Shastri so Tukaram’s books are thrown in the waters of Indrayani. When none of this works, then he will appeal to Shivaji Maharaj, who will tempt Tukaram with rich clothes and jewellery-and failing, who will become a disciple. Seeing a Hindu king thus ‘unable to protect Sanatana dharma’, Salomalo will go to a ‘vidharmi raja’, the Sultan of Chakan. When that too fails, Salomalo literally-in this case visually-slinks out of the narrative, exiting the frame (right of frame) never to return again.

If this shows, how extraordinarily well the film episodes are constructed and placed one after the other-we do not have space in this article to go deeper into any-let us note: this is not all. It is my opinion that the charm and durable impression of the film in the minds of its audiences result from several factors and one of it is the amazing discursiveness carried by the individual episodes and their overall structuring.

The first time Salomalo appears it is as if there is a serious disturbance of the calm (shanta) mood, set in by the first two iconic shot and the singing of Pagnis. The Salomalo sequence is ‘wiped off’ with a cinematic wipe and the Tuka-image (and singing) is brought back. This ‘wipe’ is also meant to bring in completely a different ‘topic.’ Now we see a different kind of Bhakti and the business of singing songs. Tuakaram’s wife, a devotee of the local (more grass-root level) Goddess Mangalaai, sings an ovi, songs women in Maharashtra traditionally sang while at their daily chore. Her devotion, her firm conviction about and love for her God and everything else she has brought with her from her natal family are made to contrast with Tukaram’s devotional mode and level of attainment. And so, it is Jijai with who the first two miracles of the film are attached. But at the same time, Jijai is not put in any oppositional binary with Tukaram. Her characterization will run parallel to that of the Tukaram character. Not only is this one of the very rare films in India to portray so extensively and so durably a religious system co-existent with the more mainstream (bhakti and sanatan) ones, but what is most amazing is Jijai is not shown to convert to her husband’s religious belief. In the context of India and its multiple religious systems and beliefs co-existing over centuries, such a representation needs more discussion, but we must here stop with the amusing observation that often a vast section of the audience has always been (and this is so since the first release of the film) taken in more with the representation of Jijai than that of Tukaram.

After the introduction of the wife, we see our hero in his room, sitting alone and writing his verses. Next, he is in the temple; and he is asked never to enter the temple again. Tukaram bids a tearful farewell to Panduranga. After this, we see him on a hilltop engaged in singing and meditation. So, the three locations where we see Tukaram initially in the film is: the house, the temple and the seclusion of nature. These are traditionally the three places designated for meditative worship. After this, the new location for the sant will be his work place. New, from the point of view of tradition, for it is known Tukaram had become a religious person after he gave up his worldly duties (before that he had been a farmer, a grocer and also the local moneylender-a task his family was entrusted by the rulers). The narrative woven in 1936 injects a thoroughly contemporary element in the life of Tukaram; he becomes a daily-wage worker. Had Tukaram remained a popular revered sage singing and meditating in the temple there would be no story, no drama; ‘traditional’ elements alone would not have produced such an effective film narrative. Tukaram enters the narrative-dramatic arena, as he goes out in the world, takes up a job, interacts with family and the village-community. This film is so remarkable, not only because it, as shown in the beginning of the paper, illustrates Bhakti in Maharashtra, but also because it is thoroughly modern. It brings forward a contemporary motto, expressed through the English proverb ‘work is worship.’ We must not forget, every narrative-literary work or cinema reveals the time it is created.

Sant Tukaram ( The Movie ) Part III

Gayatri Chaterjee

I choose to write about the Marathi film Sant Tukaram (1936) made by Damle & Fattelal. I have seen it over thirty or more times; I like very much to watch it; and continuously teach and write on it. But even so, such a choice is not a simple spontaneous gesture; it is difficult to choose any one film as the best or the greatest Indian film. To say, ‘I choose to talk about the Marathi film Sant Tukaram’ is also to say what guided me to this choice. For sure there are some other film one could have chosen.

So, this piece is about a film called Sant Tukaram and about a choice; about strong and close relationships a viewer forms with a film through repeated viewing, continuous study, and efforts to understand and analyze it. While teaching cinema, one does not choose only those films one is fond of; one uses in the classroom all kinds of films, with different level and quotient of excellence and appeal, with different histories of critical and audience response. Film courses come with specific requirements and the teacher designs her course-material accordingly. The choice of talking or writing about a specific film, too, is invariably guided and shaped by specific factors and needs, linked to various discourse and discussion. [1] And then again, there are times someone in the classroom or someone outside feels sheer love or fondness for a particular film—and then there is the need and the business of verbalizing that. ‘What is this I am feeling after seeing this film’ is also something one must address while analyzing or understating a film.

Sant Tukaram seems to generate very interesting effects on viewers of all age, coming from all sections of society, or from all parts of the world. Anecdotal modes are not usually expected in a serious article, but a very recent experience made me think on this film yet again and hence this piece. A girl attending a foreign India Study Program had opted for a (credited) course on Indian Cinema. Initially, her heart was not fully in her class and studies, till she saw Sant Tukaram. The film, she told me, was the gift she was taking back from India to her family—in the form of a VCD. A devout Muslim family in Canada, they would appreciate seeing a ‘rare’ (she had never heard of the film before) and wonderful film like this. While talking about her own experience of the film, she wanted to know if I would understand if she described it as a spiritual experience. For a teacher, to speak about the film now was also to fully engage with this appeal and challenge; it meant probing why and how such a response is connected with the film. This happens often enough—students see films from all over the world and when Sant Tukaram is shown, they ask what is this special feeling they have just had—something quite different from other viewing experiences.

One usual oft-repeated response to such observation and comments people have is: Sant Tukaram uses the ‘universal language of Bhakti’ and viewers, immaterial of race caste creed etc, respond to that. But then, Dharmatma (made a year ago in 1935) and Gopal-Krishna (made a year later)—both by the Prabhat Film Company—are also based on the tradition of Bhakti. But we do not respond to these films the same way. So, another question follows: over the past eight and nine decades, many films have been made on this very popular Maharashtra-sant; but we cannot say all those films are equally good or equally appreciated. For example when this particular film was made contemporary reviewers and writers wrote about how just a few years ago, Sant Tukaram aani Jai Hari Vitthala (1932) by Babajirao Rane had failed to impress the viewers. This information is of extreme importance, as that film was an adaptation of a phenomenally successful play by Rajapurkar Natya Company. Unfortunately that early film does not exist or else we would have understood in what ways the audience and the intelligentsia then had exercised discrimination and judgment over these two films. [2]

Some others explain: Sant Tukaram uses the ‘universal language of cinema’; it is a simple and naïve film and so we take to it easily. Are those other films complex, then? Do they use a language other than that particular ‘universal language of cinema’ that is used in Sant Tukaram? Evidently, the above two explanations are flawed; but explain, we must. And the explanations and answers belong both to the world of Bhakti and Films Studies. The question remains though: what is so special about this Sant Tukaram? Dilip Chitre had once said, partly questioning me and partly himself: ‘we say “it is a good film;” but what do we mean by good—what does it mean in this case, this good!’