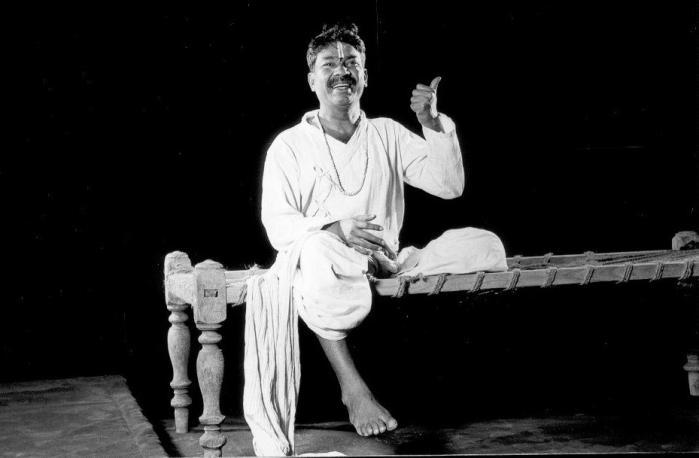

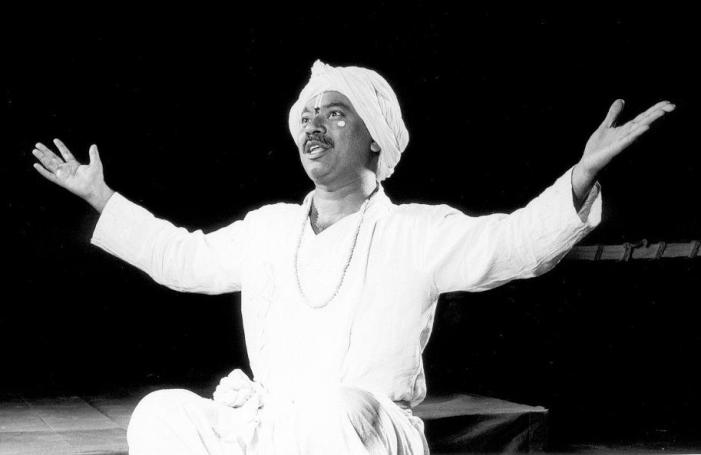

|| Tukaram ||

Tukaram is very dear to me.- Mahatma Gandhi

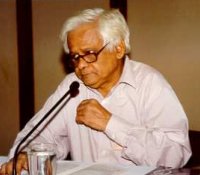

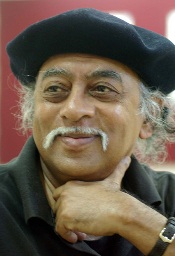

Introduction ( Says Tuka ) - Dilip Chitre

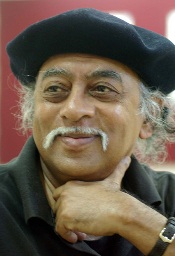

Dilip Purushottam Chitre (born 1938) is one of the foremost Indian writers and critics to emerge in the post Independence era. Apart from being a very important bilingual writer, writing in Marathi and English, he is also a painter and filmmaker.

Dilip Purushottam Chitre (born 1938) is one of the foremost Indian writers and critics to emerge in the post Independence era. Apart from being a very important bilingual writer, writing in Marathi and English, he is also a painter and filmmaker.

Among Chitre’s honours and awards are the Prix Special du Jury for his film 'Godam' at the Festival des Trois Continents at Nantes in France in 1984, the Sahitya Akademi Award (1994) for his Marathi book of poems 'Ekoon Kavita-1' and the Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize (1994) for his English translation of the poetry of the 17th century Marathi poet-saint Tukaram 'Says Tuka'. He was Member of the International Jury at the recent Literature festival Berlin, 2001.He is Honorary Editor of the quarterly ‘New Quest’.

Introduction Part I of IV (Says Tuka)

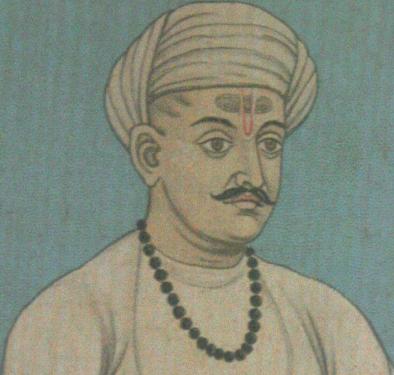

Tukaram was born in 1609 and vanished without a trace in 1650.What little we know of his life is a reconstruction from his own autobiographical poems, the contemporary poetess Bahinabai's memoirs in verse, and the latest biographer of Marathi poet-saints, Mahipati's account. The rest is all folklore , though it cannot be dismissed on those grounds alone. Modern scholars such as the late V.S.Bendre have made arduous efforts to collate evidence from disparate contemporary sources to establish a well-researched biography of Tukaram. But even this is largely conjectural.

There is a similar mystery about Tukaram's manuscripts. The Vithoba-Rakhumai temple in Tukaram's native village, Dehu, has a manuscript on display that is claimed to be in Tukaram's own handwriting. What is more important is the claim that this manuscript is part of the collection Tukaram was forced to sink in the local river Indrayani and which was miraculously restored after he undertook a fast-unto-death. The present manuscript is in a somewhat precarious condition and contains only about 250 poems. At the beginning of this century the same manuscript was recorded as having about 700 poems and a copy of it is still found in Pandharpur. Obviously, the present manuscript has been

vandalized in recent times, presumably by scholars who borrowed it from unsuspecting trustees of the temple. It is important to stress that the claim that this manuscript is in Tukaram's own handwriting is not seriously disputed. It is an heirloom handed down to Tukaram's present descendants by their forefathers. Tukaram had many contemporary followers. According to the Warkari pilgrims' tradition , fourteen accompanists supported Tukaram whenever he sang in public. Manuscripts attributed to some of these are among the chief sources from which the present editions of Tukaram's collected poetry derive. some scholars believe Tukaram's available work to be in the region of about 8000 poems. This is a subject still open to research. The standard edition of the collected poetry of Tukaram is still the one "printed and published under the patronage of the Bombay Government by the proprietors of the Indu-Prakash Press" in 1873. This was reprinted with a new critical introduction in 1950 on the occasion of the tri-centennial of Tukaram's departure and has been reprinted at regular intervals ever since by the Government of Maharashtra. This collection contains 4607 poems in a certain numbered sequence.

There is a similar mystery about Tukaram's manuscripts. The Vithoba-Rakhumai temple in Tukaram's native village, Dehu, has a manuscript on display that is claimed to be in Tukaram's own handwriting. What is more important is the claim that this manuscript is part of the collection Tukaram was forced to sink in the local river Indrayani and which was miraculously restored after he undertook a fast-unto-death. The present manuscript is in a somewhat precarious condition and contains only about 250 poems. At the beginning of this century the same manuscript was recorded as having about 700 poems and a copy of it is still found in Pandharpur. Obviously, the present manuscript has been

vandalized in recent times, presumably by scholars who borrowed it from unsuspecting trustees of the temple. It is important to stress that the claim that this manuscript is in Tukaram's own handwriting is not seriously disputed. It is an heirloom handed down to Tukaram's present descendants by their forefathers. Tukaram had many contemporary followers. According to the Warkari pilgrims' tradition , fourteen accompanists supported Tukaram whenever he sang in public. Manuscripts attributed to some of these are among the chief sources from which the present editions of Tukaram's collected poetry derive. some scholars believe Tukaram's available work to be in the region of about 8000 poems. This is a subject still open to research. The standard edition of the collected poetry of Tukaram is still the one "printed and published under the patronage of the Bombay Government by the proprietors of the Indu-Prakash Press" in 1873. This was reprinted with a new critical introduction in 1950 on the occasion of the tri-centennial of Tukaram's departure and has been reprinted at regular intervals ever since by the Government of Maharashtra. This collection contains 4607 poems in a certain numbered sequence.

In sum the situation is :

- i. We do not have a single complete manuscript of the collected poems of Tukaram in the poet's own handwriting.

- ii . We have some contemporary versions but they do not tally.

- iii. We have many other versions on the oldest texts and occasionally, poems that are not found elsewhere.

The various versions of Tukaram's collected poems are transcriptions made from the oral tradition of the Varkaris and/or copies of the original collection or contemporary "editions " thereof.

This is a tangled issue best left to the experts. The point to be noted is that every existing edition of Tukaram's collected works is by and large a massive jumbled collection of randomly scattered poems of which only a few are in clearly linked sequences and thematic units. There is no chronological sequence among them. Nor, for that matter, is there an attempt to seek thematic coherence beyond the obvious and broad traditional divisions made by each anonymous "editor" of the traditional texts.

One of the obvious reasons why Tukaram's life is shrouded in mystery and why his work has not been preserved in its original form is because he was born a Shudra, at the bottom of the caste hierarchy. In Tukaram's time in Maharashtra, orthodox Brahmins held that members all varnas other than themselves were Shudras. Shivaji established a Maratha kingdom for the first time only after Tukaram's disappearance. It was only after Shivaji's rise that the two-tier caste structure in Maharashtra was modified to accommodate the new class of kings and warrior chieftains as well as the clans from which they came as proper Kshatriyas.

For a Shudra like Tukaram to write poetry on religious themes in colloquial Marathi was a double encroachment on Brahmin monopoly. Brahmins alone were allowed to learn Sanskrit, the language of the gods" and to read religious scriptures and discourses. Although since the thirteenth century poet-saint Jnandev, there had been a dissident Varkari tradition of using their native Marathi language for religious self-expression, this had always been in the teeth of orthodox opposition. Tukaram's first offence was to write in Marathi. His second, and infinitely worse offence, was that he was born in a caste that had no right to high, Brahminical religion, or for that matter to any opinion on that religion. Tukaram's writing of poetry on religious themes was seen by the Brahmins as an act of heresy and of the defiance of the caste system itself.

In his own lifetime Tukaram had to brave the wrath of orthodox Brahmins. He was eventually forced to throw all his manuscripts into the local Indrayani river at Dehu, his native village, and was presumably told by his mocking detractors that if indeed he were a true devotee of God, then God would restore his sunken notebooks. Tukaram then undertook a fast-unto-death praying to God for the restoration of his work of a lifetime. After thirteen days of fasting,. Tukaram's sunken reappeared from the river. They were undamaged.

In his own lifetime Tukaram had to brave the wrath of orthodox Brahmins. He was eventually forced to throw all his manuscripts into the local Indrayani river at Dehu, his native village, and was presumably told by his mocking detractors that if indeed he were a true devotee of God, then God would restore his sunken notebooks. Tukaram then undertook a fast-unto-death praying to God for the restoration of his work of a lifetime. After thirteen days of fasting,. Tukaram's sunken reappeared from the river. They were undamaged.

This ordeal-by-water and the miraculous restoration of his manuscripts is the pivotal point in Tukaram's career as a poet and a saint. It seems that after this episode his detractors were silenced , at least for some time.

But Tukaram and his miraculously restored manuscript collection both disappeared after this. Some modern writers speculate on the possibility that Tukaram could have been murdered and his work sought to be destroyed. However, Tukaram was phenomenally popular during his lifetime and was hailed as "Lord Pandurang incarnate" by contemporary devotees like the poetess Bahinabai. Any attack on his person, let alone a successful attempt on his life, would not have escaped the keen and constant attention of his numerous followers. Therefore, such speculations seem wild and sensational.

But Tukaram and his miraculously restored manuscript collection both disappeared after this. Some modern writers speculate on the possibility that Tukaram could have been murdered and his work sought to be destroyed. However, Tukaram was phenomenally popular during his lifetime and was hailed as "Lord Pandurang incarnate" by contemporary devotees like the poetess Bahinabai. Any attack on his person, let alone a successful attempt on his life, would not have escaped the keen and constant attention of his numerous followers. Therefore, such speculations seem wild and sensational.

Around 1629, there was a terrible famine followed by waves of epidemic diseases. Tukaram's first wife, Rakhma, was an asthmatic, and probably also a consumptive woman. Though he had been married to his second wife Jija while Rakhma was still alive, Tukaram loved Rakhma very dearly. Rakhma starved to death during the famine while Tukaram watched in helpless horror.

Shivaji was born within a year of the terrible famine that ruined Tukaram's family as it did thousands of others. Even after Shivaji's rise a few years later, things could not have been better for the average farmer in the villages of Maharashtra. Though Shivaji's brief reign was popular by all accounts, he was battling the might of the Mughal military machine, waging a constant guerilla war.

Relative peace and stability returned to Maharashtra only about a century after Tukaram. While it had tenaciously survived the political turmoil surrounding it, the Varkari religious movement witnessed a revival only after the situation became more settled. Tukram's great grandson, Gopalbuwa, played an important role in this revival. Otherwise, for four generations the history of Tukaram tradition remained obscure even though increasing numbers of people claimed to have become Tukaram's followers.

Introduction Part II of IV - Dilip Chitre

A brief survey of Tukaram's life and his circumstances give us an idea of the universality of his experience at this-worldly level which, in his poetry, acquires other worldly dimensions.

Tukaram was the second son of his parents, Bolhoba Ambile ( or More) and Kankai. Bolhoba had inherited the office of the village Mahajan from his forefathers. Mahajans were a reputed family of traders in a village, kasba or city appointed to supervise certain classes of traders and collect revenue from them. Tukaram's family owned a comparatively large piece of prime agricultural land on the bank of the river Indrayani in Dehu. Several generations of Tukaram's ancestors had farmed this land and sold its produce as merchant-farmers. Though, technically regarded as Shudras by Brahmins, they were by no means socially or culturally backward. being traders by profession, they learned to read and write as to maintain accounts of financial transactions. This was presumably the kind of education Tukaram had. The rest was his own learning from whatever sources he had access to. Considering the situation of the small village of Dehu, it is exciting to speculate on the sources of Tukaram's wealth of information and the depth of his learning.

The early death of his parents and the renunciation of worldly life by his elder brother thrust upon Tukaram the role of the head of his extended Hindu family at a fairly young age. As mentioned earlier in another context, Tukaram was married a second time as his first wife was chronically ill. He had six children and had to raise a younger brother as well.

Before he was twenty-one, Tukaram had to witness a series of deaths from amongst his loved ones including his mother, his father, his first wife, and children. The famine of 1629, during which he lost his wife, was a devastating experience for Tukaram. The horror of the human condition that Tukaram speaks of comes from this experience. After the famine, Tukaram lost all urge to lead a householder's life. He showed no interest in farming or the family's trade. Presumably the famine, but also some other circumstance of which we have no details, seems to have reduced Tukaram first to penury and then to final humiliation of bankruptcy. He was unable to repay debts he had incurred and the village council stripped him of his position as Mahajan and passed strictures against him. He incurred the displeasure of the village Patil(Headman).

Tukaram became totally withdrawn. He started to shun the company of the people. He began to sit alone in a corner and brood. Soon, he started going off into wilderness for long spells. Meanwhile, his wife had to fend for herself and the children as Tukaram paid little attention to his household responsibilities.

The Ambiles (Mores) of Dehu had been devoted Varkaris for several generations before Tukaram. Lord Vithoba of Pandharpur was their family deity. There was a shrine of Vitthal built by an ancestor of Tukaram on land owned by the family in Dehu. A series of traumatic events in his personal life not only made Tukaram introspective but also made him turn his attention to the deity in whom his forefathers had placed their unswerving faith. Their ancestral shrine of Vitthal happened to be in a state of disrepair at this time and Tukaram restored this shrine even though his immediate family was reduced to abject misery.

He now began to spend most of his time in the shrine of Vitthal or its precincts, singing songs composed by earlier poet-saints in praise of the deity. He totally disregarded the pleas of his wife and the counsel of his friends and virtually stopped working for a living. He became a dropout and perhaps an object of pity or contempt among many of his fellow-villagers. His wife and some of his fellow-villagers saw this as a form of madness because Tukaram was lost to the world and had broken away from its routines and practical bonds. However, his total devotion to Vitthal and his compassion for everybody and all forms of life slowly won him the admiration of people.

Some time at this juncture, Tukaram had a revelatory dream in which the great saint-poet Namdeo and Tukaram's deity Vitthal appeared and initiated Tukaram into poetry, informing Tukaram that his mission in life was "to make poems". "Poems" of course meant "abhangs" to be sung in praise of Vithoba as Namdeo himself had done. The dream made reference to a pledge made by Namdeo to Vitthal that he would compose "one billion abhangs" in His praise. Namdeo had obviously been unable to achieve this steep target in his lifetime and he therefore asked Tukaram to complete the task. This dream or revelation which he saw while in state of trance was so vivid that Tukaram was convinced of its "reality". This changed his life. He had found his true vocation.

The divine revelation that he was a poet did not cause Tukaram to go into ecstasy. Instead, he began to suffer from anxiety, doubt and pangs of conscience. One of Tukaram's characteristics was his absolute honesty and accountability to himself. He would not tell a lie even in a poem. The knowledge that his task in life was to write poems in praise of Vitthal made Tukaram a restless and troubled soul. He had never experienced God. How was he going to praise some –thing he had never experienced himself? He had been a honest trader. He vouched for the quality of every item he sold. He bought goods only after critically testing them. He did not cheat anyone in any transaction. Nor would he allow himself to be cheated. Tukaram treated poetry as a serious business from the outset. To him, all poetry was empirical and so was religion. Experience or "realization" was the crucial test. In one of his poems, presumably written at this juncture, Tukaram says in effect, "Whereof I have no experience, thereof I cannot sing. How can I write of You, O Vitthal, when I have not personally experienced Your being?"

Yearning for an experience of God became the chief theme of poetry for Tukaram in his first major phase of work. Meanwhile, he continued to record his poems the human conditions as witnessed by him and also his experiences just prior to his realization that he was to be a poet of God.

Having become a poet, Tukaram continued to go off for long periods of time, away from the hub of human life and society, to meditate

and seek enlightenment.

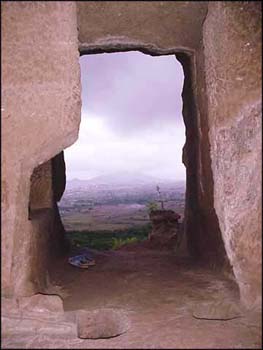

Two hills in the vicinity of Dehu were his favourite retreats. The first is the Bhandara hill, where, in a small cave which is a relic of Buddhist times, he composed many of his abhangs. The second is the Bhamchandra hill, where, some years later, he meditated for a full fifteen days before experiencing mystical illumination and beatitude. This event is distinct from another instance of initiation by a guru during a trance that Tukaram has described elsewhere. In this latter event, Tukaram was dreaming that he was going to a river for a dip when he wassuddenly confronted by a holy man who placed his hand on Tukaram's head and gave him the mantra, "Ram Krishna Hari" to chant. This holy man told

Tukaram that his name was "Babaji" and that he was a lineal spiritual descendant of the gurus Raghav Chaitanya and Keshav Chaitanya. When Tukaram was given this mantra, he felt his entire being come alive. He experienced a fullness of being he had never before felt.

and seek enlightenment.

Two hills in the vicinity of Dehu were his favourite retreats. The first is the Bhandara hill, where, in a small cave which is a relic of Buddhist times, he composed many of his abhangs. The second is the Bhamchandra hill, where, some years later, he meditated for a full fifteen days before experiencing mystical illumination and beatitude. This event is distinct from another instance of initiation by a guru during a trance that Tukaram has described elsewhere. In this latter event, Tukaram was dreaming that he was going to a river for a dip when he wassuddenly confronted by a holy man who placed his hand on Tukaram's head and gave him the mantra, "Ram Krishna Hari" to chant. This holy man told

Tukaram that his name was "Babaji" and that he was a lineal spiritual descendant of the gurus Raghav Chaitanya and Keshav Chaitanya. When Tukaram was given this mantra, he felt his entire being come alive. He experienced a fullness of being he had never before felt.

Tukaram himself has described these experiences in his poems and there is no ambiguity about them. Unfortunately, the chronology of these events is difficult to determine except in a broad way. Tukaram must have been thirty years old or more by the time the latter of these experiences occurred. A prominent modern biographer of Tukaram, the late V.S. Bendre, has laid great emphasis on Tukaram's dream initiation by "Babaji" and the guru-lineage it signifies. I suspect that Bhakti has roots in folk-religion and therefore Brahmin and caste Hindu people always try to "upgrade" a Bhakta by presenting him as a "yogi" or an "initiate" of some esoteric order or another. Bendre appears to me to have been attempting to "Brahminize" Tukaram through "yogic" and "mantric" initiation rites performed by a "proper" guru. This seems to be an attempt to authenticate a natural and self-made Bhakta. But to me the meaning of these stories is almost the opposite: to a "Shudra" the guru can appear only in a "dream" or a trance.

Now the last and the most spectacular decade in Tukaram's life begins. Though Tukaram was only about thirty years old at this time, he had been writing poetry for nearly ten years. In his poetry, Tukaram had depicted with great honesty his own past life and his anguished search for God. With his recent mystical enlightment, his poetry acquired a magical quality. His songs began to attract people from distant places. The younger poetess Bahinabai came to Dehu all the way from Kolhapur just to witness Tukaram's divine performance of his poetry in front of the image of Vitthal in the shrine near his ancestral house. Though Bahinabai's account of her visit to Dehu refers to a period just a few years before Tukaram's disappearance, from her description we get some idea of the charismatic influence of Tukaram upon his contemporaries throughout Maharashtra. The water-ordeal that has been referred to earlier had already taken place before Bahinabai's visit to Dehu. The miraculous restoration of his manuscripts that had been consigned to the river for thirteen days was surely a major factor contributing to the legendary status which Tukaram acquired in, his lifetime. Bahinabai has described Tukaram singing his abhangs as "Lord Pandurang incarnate". "Whatever Tukaram writes is God," says Bahinabai.

Tukaram disappeared at the age of forty-one. Varkaris believe that Vitthal Himself carried Tukaram away to heaven in a "chariot of light". Some people believe that Tukaram just vanished into thin air while singing his poetry in front of an ecstatic audience on the bank of the river Indrayani in Dehu. Some others as I have said, speculate that he was murdered by his enemies. Still others think that he ended his own life by drowning himself into the very river where his poems had been sunk earlier. Reading his farewell poems, however, one is inclined to imagine that Tukaram bade a proper farewell to his close friends and fellow-devotees and left his native village for some unknown destination with no intention of returning. He asked them to return home after their having walked a certain distance with him. He told them that they would never see him again as he was "going home for good". He told them that from then on only "talk about Tuka" would remain in "this world".

This, in short, is the story of Tukaram's life as it emerges from his own poems. One can see from it that from absolutely ordinary origins and after having gone through experiences accessible to average human beings anywhere. Tukaram went on an extraordinary voyage of self-discovery while continuing to record every stage of it in detail in his poetry. His poetry is a unique document in human history, impeccably centered in the fundamental problems of being and defining poetry as both the being of language and the language of being: the human truth.

Introduction Part III of IV - Dilip Chitre

The first, and by far the only complete translation of Tukaramachi Gatha or The Collected Tukaram into English was done by J. Nelson Fraser and K.B. Marathe. This was published by the Christian Literature Society, Madras (1905-1915). The only other European language version of selected poems of Tukaram is G.A. Deleury's Toukaram :Psaumes du perlerin (Gallimard, Paris, 1956). Fraser and Marathe's translation comprises 3721 poems in all. Justin E. Abbott's monumental 11-volume series, Poet-Saints of Maharashtra (Scottish Mission Industries, Poona, 1926) and Nicol Macnicol's Psalms of Maratha Saints (Christian Literature Society, Calcutta, 1919) contain much fewer. Fraser and Abbot have both attempted prose paraphrases while Macnicol has superimposed a heavily stylized verse-form quite alien to the fluid colloquial folk-style of the original. Deleury's 101 poems in French translation are the only European attempt to create a poetic analogue of Tukaram's original work. The distinguished Anglo-Marathi poet, Arun Kolatkar has published 9 translations of Tukaram's poems (Poetry India, Bombay, 1966) and my own earlier versions of Tukaram have appeared in Fakir, Delos, Modern Poetry in Translation, Translation and the South-Asian Digest of Literature.

This is hardly an adequate bibliography considering Tukaram's towering stature as a poet and his pervasive influence on Marathi language and literature. He represents the vital link in the mutation of a medieval Marathi literary tradition into modern Marathi literature. His poems (nearly 5000) encompass the entire gamut of Marathi culture. The dimensions of his work are so monumental that they will keep many future generations of translators creatively occupied. In a sense, therefore, Tukaram is a poet who belongs more to the future than to a historically bound specific past.

The translators of Tukaram fall into different categories. Fraser and Abbott have rendered Tukaram into prose rather like representing a spontaneous choreography as a purposeful walk. Macnicol turns the walk into what seems like a military march. Only Deleury and Kolatkar approach it as dance and in the spirit of dance. Deleury dwells on the lyrical nuance and the emotional intensity of the original. Kolatkar concentrates on the dramatic, the quick and the abrupt, the startling and the cryptic element in Tukaram's idiom. This is hardly enough to give an idea of the range, the depth and the complexity of the source text as a whole. Tukaram forces one to face the fundamental problem of translating poetry: beneath the simple and elegant surface structure of the source text lies a richer and vastly complex deep structure that the target text must somehow suggest. This is nothing short of a project lasting an exasperating lifetime. It is much easier to play-act the role of Tukaram as a stylized vignette in whatever the prevailing etat de langue permits. The culture of poetry is more biased and partisan than the culture of translation. One would hesitate to elaborate on this point at this juncture; but it needs to be made albeit in passing.

Problems of translation can be compared to problems of instrumentation. The naked eye does not see what can be seen only through a telescope; but a radio telescope literally makes the invisible visible. An electron microscope is designed to "see" what lies beyond sight by definition.

Unfortunately, there is no equipment engineered to read beneath the surface of a specific source text. If the target text is only an attempt to create a model of the source text, then every aspect of the source text becomes equally sacrosanct and translation becomes obviously impossible.

Unless the translator presumes or directly apprehends how the source text functions, he cannot begin to look for a possible translation. Poems function in delicate, intricate and dynamic ways. Their original existence does not depend on specific audiences or the possibility of eventual translators. No translation can absolutely do away with the idea of the source text as an autonomously functioning whole in another linguistic space and time.

There is an implicit strangeness in every translated work, especially in translated poetry. A translated poem is at best, an intimate stranger among its counterparts in the target language. The stranger will retain traces of an odd accent; peculiar turns of phrase, exotic references and even a wistful homesick look. These are happy signs that poetry is born and is alive and kicking elsewhere too. That other minds do exist is a fact that should be as often celebrated as it is mourned by some puritanical critics.

Religion in Maharashtra, in Tukaram's time, was a practice that separated communities, classes and castes. Bhakti was the middle way between the extremes of Brahminism on the one hand and folk religion on the other. It was also the most democratic and egalitarian community of worshippers, sharing a way of life and caring for all life with a deep sense of compassion. The legacy of Jainism and Buddhism had not disappeared altogether in Maharashtra. It was regenerated in the form of Bhakti. Tukaram's penetrating criticism of the degenerated state of Brahminical Hinduism, and his scathing comments on bigotry and obscurantism, profiteering and profligacy in the name of religion, bear witness to his universal humanistic concerns. He had the abhorrence of a true realist for any superstitious belief or practice. He understood the nature of language well enough to understand how it can be used to bewitch, mislead and distort. He had a healthy suspicion of god-men and gurus. He believed that the individual alone was ultimately responsible for his own spiritual liberation. He was not an escapist. His mysticism was not rooted in a rejection of reality but rather in a spirited response to it after its total acceptance as a basic fact of life. Tukaram's hard common sense is not contracted by his mysticism: the two reinforce each other.

The Marathi poet-saints are an exception to the general rule that Indian devotional literature shows little awareness of the prevailing social conditions. The Marathi "saints", both implicitly and explicitly, questioned the elitist monopoly of spiritual knowledge and privilege embodied in the caste hierarchy. They were strongly egalitarian and preached universal love and compassion. They trusted their native language, Marathi, more than Sanskrit of the scriptures or the erudite commentaries thereon. They made language a form of shared religion and religion a shared language. It is they who helped to bind the Marathas together against the Mughals on the basis not of any religious ideology but a territorial cultural identity. Their egalitarian legacy continues into modern times with Jotiba Phule, Vitthal Ramji Shinde, Chattrapati Shahu, Sayaji Rao Gaekwar and B.R. Ambedkar - all outstanding social reformers and activists. The gamut of Bhakti poetry has amazing depth, width and range: it is hermitic, esoteric, cryptic, mystical; it is sensuous, lyrical, deeply emotional, devotional, it is vivid, graphic, frank, direct; it is ironic, sarcastic, critical; it is colloquial, comic, absurd; it is imaginative, inventive, experimental; it is intense, angry, assertive and full of protest. In the 4000-plus poems of Tukaram handed down to us by an unbroken oral tradition, there are poems to which all the above adjectives fit.

The tradition of the Marathi saints conceives the role of a poet in its own unique way and I am sure this has a deep ethno-poetic significance. Bhakti is founded in a spirit of universal fellowship. Its basic principle is sharing. The deity does not represent any sectarian dogma to the Bhakta but only a common object of universal love or a common spiritual focus. Poetry is another expression of the same fellowship. Tukaram may have written his poems in loneliness but he recited them to live audiences in a shrine of Vitthal. Hundreds of people gathered to listen his poetry. The poetess Bahinabai a contemporary and a devoted follower of Tukaram has described how Tukaram in a state of trance, chanted his poems while an enraptured audience rocked to their rhythm. This has been a tradition from the time of Jnanadev (1275-1296), the founder of Marathi poetry and the cult of Vithoba and Namdeo (1270-1350), the great forerunner of Tukaram.The audience consisted of common village-folk, including women and low-caste people, thrilled by the heights their own language scaled and stirred by the depths it touched.

Paul Valery defines the difference between prose and poetry as comparable to the difference between walking and dancing and Tukaram's recitation must have seemed to his audience like pure dance, turning nothingness into space.

Life, in all its aspects was the subject of such poetry. Tukaram himself believed that he was only a medium of the poetry, saying, "God speaks through me." This was said in humility and not with the pompous arrogance of a god-man or the smug egoism of a poet laureate.

The saints are perhaps inaccurately called so because the Marathi word "sant" used for them sounds so similar. The Marathi word is derived from the Sanskrit "sat" which denotes being and awareness, purity and divine spirit, wisdom and sagacity, the quality of being emancipated and of being true. The relative emphases are somewhat different in the Christian concept of sainthood, though there is an overlap.

The poet-saint fusion in Marathi gives us a unique view of poetry itself. In this view, moral integrity and spiritual greatness are critical characteristics of both poetry and the poet.

Tukaram saw himself as primarily a poet. He has explicitly written about being a poet, the responsibility of a poet, the difficulties in being a poet and so forth. He has also criticized certain kinds of poetry and poets. It is clear that he would have agreed with Heidegger that in poetry the language becomes one with the being of language. Poetry was, for him, a precise description of the human condition in its naked totality. It was certainly not an effete form of entertainment for him. Nor was it ornamental. Language was a divine gift and it had to be returned to its source, via poetry, with selfless devotion.

This would sound like a cliché, but Tukaram's genius partly lies in his ability to transform the external world into its spiritual analogue. The whole world became a sort of functional metaphor in his poetry, a text. His poems have an apparently simple surface. But beneath the simple surface lies a complex understructure and the tension between the two is always subtly suggested.

The famous "signature line" of each poem, "Says Tuka" opens the door to deeper structure. Aphoristic, witty, satirical, ironic, wry, absurd, startling or mystical, these endings of Tukaram's poems often set the entire poem into sudden reverse motion. They point to an invisible, circular or spiral continuity between the apparent and the real, between everyday language and the intricate world-image that it often innocently implies.

Thus, Tukaram sees the relationship between God and His devotee as the relationship between God and his devotee. Tukaram is not proposing the absolutely external existence of God, independent of man. He knows that it is the devotee who creates an anthropomorphic image of God. He know that in a sense it is a make-believe God entirely at the mercy of his creator-devotee using a man-made language.

Tukaram is interested in a godlike experience of being where there is no boundary between the subjective and the objective, the personal and the impersonal, the individual and cosmic. He sees his own consciousness as a cosmic event rooted in the everyday world but stretching infinitely to the deceptive limits of awareness. "Too scarce to occupy an atom," he writes, "Tuka is as vast as the sky."

One more striking aspects of Tukaram's poetry is its distinct ethno-poetics or the Marathi-ness of its conception.

Medieval Marathi poetry developed in two divergent directions. One continued from the Sanskrit classics - both religious and secular - and from the somewhat different classicism of Prakrit poetry. In either case, it followed older, established models and non-native literary sources. Imitations of Sanskrit models in a highly Sanskritized language and using Sanskrit prosody as "well as stylistic devices characterize this trend in Marathi literature. These "classicists" neglected or deliberately excluded the use of native resources of demotic, colloquial Marathi. Luckily, though this trend has continued in Marathi for the last 700 years, only minority of writers (of not too significant talent) have produced classicist literature.

Others, starting from the pioneer of Marathi Bhakti poetry, Jnanadev, took precisely the opposite course. They used the growing resources of vigorously developing Marathi language to create a new literature of their own. They fashioned out a Marathi prosody from the flexible meters of the graceful folk-songs of women at work in homes and devotees at play in religious folk-festivals. They gave literary form to colloquial speech, drawing their vocabulary from everyday usage of ordinary people. The result was poetry far richer in body and more variegated in texture than the standardized work of the "classicists". People by many voices, made distinctive by many local and regional tonalities and enriched by spontaneous folk innovation, Bhakti poetry became a phenomenal movement bringing Marathi-speaking people together as never before. This poetry was sung and per-formed by audiences that joined poet-singers in a chorus. Musical-literary discourses or keertans that are a blend of oratory, theatre, solo and choral singing and music were the new art form spawned by this movement. Bhajan was the new form of singing poetry together and emphasizing its key elements by turning chosen lines into a refrain. These comprise a new kind of democratic literary transaction in which even illiterates are drawn to the core of a literary text in a collective realization of some poet's work. This open-ended and down-to-earth nativism found its fullest expression in Tukaram, three centuries after Jnanadev and Namdeo had broken new ground by founding demotic Marathi poetry itself.

Bhakti poetry as a whole has so profoundly shaped the very world-image of Marathi speakers that even unsuspecting moderns cannot escape its pervasive mould. But Tukaram gave Bhakti itself new existential dimensions. In this he was anticipating the spiritual anguish of modern man two centuries ahead of his time. He was also anticipating a form of personal, confessional poetry that seeks articulate liberation from the deepest traumas man experiences and represses out of fear. Tukaram's poetry expresses pain and bewilderment, fear and anxiety, exasperation and desperateness, boredom and meaninglessness - in fact all the feelings that characterize modern self-awareness. Tukaram's poetry is always apparently easy to understand and simple in its structure. But it has many hidden traps. It has a deadpan irony that is not easy to detect. It has deadly paradoxes and a savage black humour. Tukaram himself is often paradoxical: he is an image-worshipping iconoclast; he is a sensuous ascetic; he is an intense Bhakta who would not hesitate to destroy his God out of sheer love. Tukaram knows that he is in charge of his own feelings and the meaning of his poetry. This is not merely the confidence of a master craftsman; it is much more. It is his conviction that man is responsible for his own spiritual destiny as much as he is in charge of his own worldly affairs. He believes that freedom means self-determination. He sees the connection between being and making choice. His belief is a conscious choice for which he has willingly paid a price.

Tukaram is therefore not only the last great Bhakti poet in Marathi but he is also the first truly modern Marathi poet in terms of temper and thematic choice, technique and vision. He is certainly the most vital link between medieval and modern Marathi poetry.

Tukaram's stature in Marathi literature is comparable to that of Shakespeare in English or Goethe in German. He could be called the quintessential Marathi poet reflecting the genius or the language as well as its characteristic literary culture. There is no other Marathi writer who has so deeply and widely influenced Marathi literary culture since. Tukaram's poetry has shaped the Marathi language, as it is spoken by 50 million people today and not just the literary language. Perhaps one should compare his influence with that of the King James Version of the Bible upon speakers of the English language. For Tukaram's poetry is also used by illiterate millions to voice their prayers or to express their love of God.

Tukaram speaks the Marathi of the common man of rural Maharashtra and not the elite. His language is not of the Brahmin priests. It is the language of ordinary men such as farmers, traders, craftsman, labourers and also the language of the average housewife. His idiom and imagery is moulded from the everyday experience of people though it also contains special information and insights from a variety of sources and contexts. Tukaram transforms the colloquial into the classic with a universal touch. At once earthy and other-worldly, he is able to create a revealing analogue of spiritual life out of this-worldly language. He is, thus, able to prove how close to common speech the roots of great poetry lie. Yet his poetry does not yield the secret of its seamless excellence to even the most sophisticated stylistic analysis. He is so great an artist that his draughtsmanship seems to be an integral part of a prodigious instinct, a genius.

Tukaram's prolific output, by and large, consists of a single spiritual autobiography revealed in its myriad facets. It defies any classification once it is realized that common thematic strands and recurrent motifs homogenize his work as a whole. In the end what we begin to hear is a single voice - unique and unmistakable - urgent, intense, human and erasing the boundary between the private domain and the public. Tukaram is an accessible poet and yet his is a very difficult one. He keeps growing on you.

Introduction Part IV of IV (Says Tuka) - Dilip Chitre

I attempted my first translation of a Tukaram abhang in 1956 or , more than thirty years ago. It was the famous abhang describing the image of Vitthal - sundar te dhyan ubha vitevari. For some reason, at that time I found it comparable to Rainer Maria Rilke's Archaic Torso of Apollo and felt that the difference between Vitthal and Apollo described the difference between two artistic cultures. I was only eighteen then and should therefore be forgiven my immature and rash cross-comparison. But the fact is that the comparison persisted in my mind. Through Rilke's poem I reached back to Nietzsche's brilliant early work, Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music. This is where Nietzsche first proposed the opposition between Dionysius and Apollo and the resolution of this opposition in Attic Tragedy. I began to look at the iconography of Vitthal to contemplate its secret meaning for Varkari Bhakta poets and it was worth paying attention to the unique stance of V

The reason I recall this here is because I kept translating the same abhang periodically and my most recent version of it was done last year. Each of these versions derive from and point to the same source text. The same translator has attempted them. But can one say that anyone of them is more valid or correct or true than any other? Do these translations exist independently of the source text? Do they exist independently of one another? Or do they belong to a vast and growing body of Tukaram literature that now includes many other things in many languages besides the source text of Tukaram's collected poetry? These issues are fundamental to literary theory and to the theory of literary translation, if such a theory were po

In this connection, I would like to quote somewhat extensively from my Ajneya Memorial Lecture delivered at the South Asia Institute of the University of Heidelberg in November 1988. The theme of my lecture was the life of a translator and more specifically my life as a translator of Tukaram into a modern European language. Here are some relevant ex

"Someone has said (and I wish it was me who first said it) that when we deal with the greatest of writers, the proper question to ask is not I what we think of them but what they would have thought of us. What a contemporary European reader thinks of Tukaram is thus a less proper question to ask than what Tukaram would have thought of a contemporary European reader. Part of my almost impossible task is to make the reader of my translations aware that my translations faced a challenge I was unable to m

". ..Bhakti, the practice of devoted awareness, lies in mirroring God here and now. Tukaram was a Bhakta-poet. To understand God's being, to translate His presence, he mirrored Him. First, he thought of God, tried to picture Him in various worldly and other-worldly situations. Then he pined for Him. And finally, "possessed" by Him, He acted, through language, like God. To read Tukaram's poetry is to understand this ritual choreography as a whole; for its form is shaped by its function. Thus, in translating Tukaram, we are not merely transposing poetry but recreating a dramatic ritual of "possessed" language. This is the only aspect of Tukaram's work which is multifaceted. But it is a culture-specific aspect of his idea of the role of poetry in life as B

"This imposes comprehensive constraints upon any would-be translator of Tukaram into any modern European language. He has to be thoroughly aware of the phenomenon of Tukaram at source, not only the text but the context as well. For the text is a total cultural performance which embodies a specific tradition and an individual notion of poetry, the poet and his audience. When Tukaram claims to be a poet he is also claiming that his kind of utterance is poetry as distinct from other kinds of Marathi utterances. He and his tradition in the seventeenth century are innocent of Europe and its poetry. The source language and its literature, in this case, have no actual historical nexus with the target language. This does not rule out, however, an imaginative manipulation of the resources of the target language and literature, as available in the twentieth century, to put Tukaram's work across. In fact, our contemporary translation of Tukaram must make his work appear here and now, yet suggesting also that it is really out there. The translation must subtly contain its own perspective and imagined laws of projected perception, so that Tukaram remains a seventeenth century Marathi Bhakta-poet in English translation, and not a jeans-and-jacket-clad European talking of mystical illumination in Indi

More than three decades of translating Tukaram have helped me to learn to live with problems that can only be understood by people who often live in a no-man's land between two linguistic cultures belonging to two distinct civiliz

As I have said earlier, traditional editions of Tukaram's collected works have been compiled from later devotees' versions of orally preserved and transmitted verses. Some of them are copies of still older copies but what we have in supposedly Tukaram's own hand- writing is the remaining 250 abhangs from the hallowed heirloom of a copy in the temple at Dehu. As I have remarked, this manuscript has been gradually depleting. As a result, there is no canonical text of Tukaram's collected works. The nearest thing to an authorized version that we have access to is Tukarambavachya Abhanganchi Gatha collated and critically edited by Vishnu Parshuram Shastri Pandit with the assistance of Shankar Pandurang Pandit in 1873. It is significant to note that one of the four manuscripts used by the Pandits for their critically collated edition was the "Dehu manuscript obtained from Tukaram's own family and continuing in it as an heirloom". But according to the editors, "It is said to be in the hand-writing of Mahadevabava, the eldest son of Tukaram, and so appears to be more than two hundred years old." However, the present oldest direct lineal descendent of Tukaram, Mr. Shridharbuva More (Dehukar) informs me that the Dehu manuscript is in Tukaram's own handwriting and is referred to as the "Bhijki Vahi" or the "Soaked Not

Whether the Dehu manuscript is in Tukaram's own handwriting or not, its antiquity is not in question. Tukaram's descendants have proudly preserved this copy as an heirloom. The three other copies consulted by the Pandits for their critical edition are the Talegava manuscript of Trimbak Kasar, the Pandharpur manuscript, and the Kadusa manuscript of Gangadhar Mavala. Despite the vigilance of the editors, interpolations may have gone unnoticed in this otherwise excellent and most reliable edition. This is the principal source text I have used although I have occasionally used other Varkari editors' versions such as Jog's, Sakhare's, and Neoorgao

What struck me, as a regular reader of the collected poems of Tukaram in various editions, was not textual variations as such but the widely divergent sequencing of the abhangs. Although there are many distinct groups of abhangs that are linked by narrative or thematic connections or have subjects and topics that are clearly spelt out, there is no clue to the chronology of Tukaram's works. They appear in a random sequence and are often a rather jumbled collection of poems without individual titles. In short, what the Gatha lacks is a coherent order or an editorial plan, whether thematic or chronological. Since the Gatha as a whole is largely an autobiographical work occasionally containing narrative poems, topical poems, poems on specific themes, odes, epistolary poetry, aphoristic verses, prayers, poetry using the personae of various characters, allegories and many other types of poetry, it is difficult to understand it in to

Yet I, for one, feel compelled to have a holistic grasp of Tukaramachi Gatha. Since I perceive it as an autobiography, even if I cannot suggest a chronological order for the more than 4000 poems before me, I should be able to relate a majority of these poems to Tukaram's personality and his concerns, the key events that shaped his life and his development as a spiritual person through the various transformations his poetry goes through. This book makes an effort to understand Tukaram as a whole being with certain characteristic aspects: it is an introduction to Tukaram, the poet, and his poetry as facets of his being. I have made the same attempt in my Marathi book, Punha Tukaram, in which I present an identical selection of abhangs in the original Marathi of Tukaram with an introduction, a sort of running commentary, and an epilogue. But the Marathi book is addressed to the insider and is meant to be a critique of Marathi culture, among other things. In the present book, my bilingualism functions on an altogether different level though the two aspects are not mutually exclusive. I have tried to introduce my reader in English to the greatest of Marathi poets, assuming that they are unacquainted with works in Marathi. One of the greatest rewards of knowing this language is access to Tukaram's work in the or

This book has been divided into ten sections:

- 1. Being A Poet;

- 2. Being Human;

- 3. Being A Devotee;

- 4. Being In Turmoil;

- 5. Being A Saint;

- 6. Being A Sage;

- 7. Being In Time And Place;

- 8. Being Blessed;

- 9. Absolutely Being;

- 10. A Farewell To Being.

These ten aspects or dimensions of Tukaram's personality are integral to his being as a whole. None of them exists to the exclusion of any other. None of them can be emphasized at the expense of another. These aspects cannot be seen in any linear or serial order, whether chronological or psychological. They are perceived distinctly only because most of his personal and autobiographical poetry falls into place if grouped according to these aspects.

Perceived according to this design, Tukaram's aspects are his inner needs as well as his capabilities. They indicate his sensitivity. They point to his ethics. They imply an entire world-view. These ten aspects cover the universe of Tukaram's awareness.

Once I became aware of these ten facets of Tukaram's life and his poetry, the poems in this book selected themselves. If I have left out some very well-known abhang from this selection, the reason could be my self-imposed constraints. I have so far finalized the translation of about 600 abhangs of Tukaram. In selecting poems for this book, my guiding principle was the idea of presenting a poetic self-portrait by Tukaram. There are other ways of looking at his work that is oceanic in its immensity and this is only one of many possible beginnings.

Tukaram is part of a great tradition in Marathi literature that started with Jnanadev. Broadly speaking, it is part of the pan-Indian phenomenon of Bhakti. In Maharashtra, Bhakti took the form of the cult of Vithoba, the Pandharpur-based deity worshipped by Varkari pilgrims who make regular journeys to Pandharpur from all over the region. Jnanadev gave the Varkari movement its own sacred texts in Marathi in the form of Jnanadevi or Bhavarthadeepika (now better known as Jnaneshwari) Anubhavamrita and Changdev Pasashti, as well as several lyrical prayers and hymns. His contemporaries included Namdeo, another great Marathi poet and saint, and a whole galaxy of brilliant poets and poetesses. These poet-Bhaktas of Vithoba composed and sang songs on their regular trips to Pandharpur and back from all parts of Maharashtra. ,In the sixteenth century, the Varkari tradition produced its next great poet, Eknath and he was followed in the seventeenth century by Tukaram.

Tukaram's younger contemporary, Bahinabai Sioorkar, has used the metaphor of a temple to describe the Varkari tradition of Bhakti. She says that Jnanadev laid its foundation, Namdeo built its walls, Eknath gave it a central pillar, and Tukaram became its "crown" or "spire". As visualized by Bahinabai, the Varkari tradition was a single architectural masterpiece produced collectively by these four great poets and their several talented followers. She rightly views it as a collective work of art in which parts created in different centuries by different individuals are integrated into a whole that only the genius of a common tradition could produce.

The achievement of the Marathi Varkari poets is paralleled by only one example I can think of and that too, incidentally, is from Maharashtra. The frescoes of Ajanta and the sculptures and architecture of Ellora comprise similar continuous collective work of superbly integrated art. These were produced by a creative culture that does not lay too great a stress on individual authorship. It is a community of the imagination and a synergy of creative inspiration that sustains such work over several generations.

The secret appears to be the ethos of Bhakti.

The roots of Bhakti lie more in folk-traditions of worship than in classical Hindu philosophy. As for the Varkaris, their only philosopher was Jnanadev. Jnanadev was an ordained member of the esoteric Shaivaite Natha sect. It was novel, to say the least, for him to embrace the cult of Vithoba and to give it a philosophical basis on the lines of the Kashmir Shaivagama Acharyas' teachings. Jnanadev's mind was as brilliant and original as Abhinavgupta's. In Anubhavamrita - his seminal work in religious philosophy - Jnanadev describes Bhakti as chidvilasa or "the spontaneous play of creative consciousness". Tukaram celebrates the legacy of Jnanadev in his poetic world-view. But Tukaram reaches the ecstatic state of liberated life only after extreme suffering and an anguished search of a lifetime.

No Marathi reader can read Tukaram except in the larger context of the tradition of Varkari poetics and practice of poetry. If readers of Tukaram in translation find him rewarding then they should go deeper into the Varkari poetic tradition. They will not be disappointed. They will even discover richer resonances in the same work of Tukaram that they may have started with.

It may be worthwhile to ask what I myself have been doing with Tukaram all these years and try to give a candid answer.In retrospect, I have just gone through the vast body of Tukaram's work again and again, marked its leitmotifs, followed its major thematic strands and the often invisible but always palpable autobiographical thread. Each time, I have discovered something new. Some abhang or another that I had not noticed earlier has regularly exploded in my face. Tukaram's exquisite mastery of his medium has stunned me again and again.

This is the way I view my source-text with absolute and unashamed reverence. These are the bases of my present selection and presentation of translations. No reference to the source-text or to any other works is necessary for the reader of this book. Quite simply, these are poems in English worked out by a twentieth century poet who is no relation of Tukaram. Tukaram himself did not write any of these poems in English, a language he did not know of in all probability. Translations of poetry are speculations about missing poets and lost poetry. They are done with dowsing-rods and non-scientific instruments. But their existence as entities in their own right cannot be disputed or denied.

A large number of friends and well-wishers have supported my Tukaram "project" since 1956. I would recall them in a chronological order, as far as possible, and also name the places where I worked then. The "support" came in various forms: discussion, advice, suggestions, references, books, information, criticism, encouragement, and even financial help whenever I had no income but was working full time on my translations.

In the first phase between 1956 and 1960 in Bombay, Bandu Vaze and Arun Kolatkar.

In the second phase between 1960 and 1963, Graham Tayar, Tom Bloor, and George Smythe in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

In the third phase between 1963 and 1970, Damodar Prabhu, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Sadanand Rege, K. Shri Kumar, A.B. Shah, and G. V. Karandikar, in Bombay.

In the fourth phase between 1970 and 1975 in Bombay, Adil Jussawala, who continued to back me all the way, all the time, ever since.

Between 1975 and the end of 1977 in Iowa City and other parts of the U.S.A., Daniel Weissbort, Burt Blume, Skip and Bonny O'Connell, William Brown, Angela Elston, A.K Ramanujan, Eleanor Zelliott, Margaret Case, Jayanta Mahapatra.

Between 1978 and 1983 in Bombay and parts of Europe, Gunther D. Sontheimer, Lothar Lutze, Orban Otto, Guy Deleruy.

Between 1983 and 1985, Ashok Vajpeyi, Shrikant Varma in Bhopal and New Delhi.

Between 1985 and 1990, mostly in Pune except for two visits to Europe, I brought this book into its present shape with significant and sustained help from Adil Jussawala, Anne Feldhaus, Gunther D. Sontheimer, Lothar Lutze, G.M. Pawar, A.V. Datar, Prakash Deshpande, Chandrashekhar Jahagirdar, Rajan Padval, Namdeo Dhasal, Anil and Meena Kinikar, Philip Engblom, Shridharbuva More, and Sadanand More in different ways.

I would like to recall here that it was my maternal grandfather, Kashinath Martand Gupte, who impressed upon my mind the greatness of Tukaram when I was only a child. My paternal grandmother, Sitabai Atmaram Chitre, gave me my first insight into Bhakti. My parents my father in particular, regularly gave me books that were relevant to my work on Tukaram.

My greatest gratitude is towards my wife Viju, the first critical listener of my ideas as they evolve and of my poetry or translations. She is also the keeper of all that I possess or produce. Considering that the smallest scraps of paper with scribbled notes, scrawled messages, or intriguing squiggles have all been miraculously preserved by her in a nomadic life spent in three different continents during the last three decades, she deserves the world's greatest honour that I can personally bestow upon anyone.

This book is the product of the collective goodwill of all these people. All I own is the errors of omission and commission.

Dilip Chitre, Pune

July 1991

Glossary I of IV (Says Tuka) - Dilip Chitre

Abhang:

Literally, 1. Absolute; eternal, immutable, ceaseless, unbroken; impeccable, etc.

2. immortal, primordial; another name for Brahman; inviolable, etc.

3. a Marathi metre; also, any metrical composition in this metre. The abhang is the favourite metre of all Varkari poets since the thirteenth century and unlike classical Sanskrit-based metres it is native to Marathi speech and its colloquial forms. It is extremely flexible. It consists of four lines and each line contains three to eight syllables. It has a fluid symmetry maintained by internal or end-rhymes and is often designed to be sung. It originates most probably in oral folk-poetry. Poets such as Jnanadev, Namdev and Tukaram have given it a classic status in Marathi poetry. Most of Tukaram's compositions are in this metre and even when they are not, in exceptional cases, the term abhang is popularly used for practically all of Tukaram's metrical compositions. originates most probably in oral folk-poetry. Poets such as Jnanadev, Namdev, and Tukaram.

Avataras, (the ten)

"the Fish, the Tortoise, the Boar, the Man-Lion, the Dwarf Man, Parashu Rama, Rama, Krishna, the Buddha, and Kalki are the Ten Avataras" according to a verse in the Geeta. These, in the same order, are the incarnations (avataras) of Vishnu.

Ananta : literally,

1. endless, infinite, boundless, etc.

2. name of Vishnu.

3. name of Shesha, the serpent upon whom Vishnu sleeps.

4. the sky; space, etc.

5. used for time, eternity, etc.

6. used for Brahman, or absolute and infinite being; infinity in any sense.

Tukaram uses Ananta as both a name and an attribute of Vitthal who, to the Varkaris, is synonymous with Vishnu and Narayana, both of whom are known by many other names. Since each of these names has a unique significance, Tukaram often uses a specific name in a specific context, literally, metaphorically, or suggestively.

Bahinabai Sioorkar :

(1629-1700) is remarkable among the Marathi poet-saints not just because she is a woman; so were Muktabai and Janabai long before her; Bahinabai is unique because she was an orthodox, married Brahmin and yet was attracted to Bhakti and particularly to the poetry of Tukaram about whom she heard in distant Kolhapur from a keertan-performer called Jayaramaswami; she was obsessed by the idea of meeting Tukaram in person and dreamt that Tukaram blessed her and became her guru; this resulted in her husband beating her up in jealous fury; he was horrified that his wife, a Brahmin, should want to make a Shudra who had no scriptural knowledge her guru; however, the husband changed his mind when persuaded by another Brahmin and accompanied Bahinabai to Dehu; there they saw Tukaram and attended his keertans; Bahinabai's vivid account of Dehu and Tukaram are like a poetic journal that vividly recreates scenes in evocative detail; this is the only contemporary eyewitness account of Tukaram available to us; Bahinabai's autobiography and verses are translated into English prose by Justin E.Abbott and have been recently republished with a perceptive foreword by Anne Feldhaus.

Bhagawadgeeta:

often also referred to in the abbreviated form "the Geeta"; "The Song of the Lord" depicting the celebrated dialogue between -Arjuna and Krishna during the Mahabharata war and a section of the Bheeshmapa1Va, a chapter of the Hindu epic, Mahabharata; regarded by many Hindus as the essence of all scriptures and the revelation by Lord Vishnu of his own nature and cosmic role that explains karma, man's duty in this world and the laws that govern his behaviour, the design of human destiny, and the divine, cyclic design by which Vishnu Himself!! assumes different avatar as or incarnations in the human world to remove the specific form of evil that afflicts each Age or Epoch; this is also seen as a dialogue between the individual human ego and the Divine Self or the Whole Being of which the human individual is only a part; Jnanadev produced the first poetic transcreation of the

Bhagawadgeeta in Marathi in the thirteenth century; these acts of translation into the language of the masses must have been viewed by the Brahmin orthodoxy as acts of heresy.

Bhakta:

literally means a worshipper, a devotee, a votary, an adorer, etc.; it is useful to remember that the original Sanskrit word also means:

1. (a share) allotted, distributed, assigned; as such a Bhakta is given "his lot" or "his share of the Divine";

2. divided; applied to a Bhakta, this may assume a spiritual significance;

3. served, worshipped;

4. engaged in, attentive to;

5. attached or devoted to; loyal, faithful.

Bhakti:

devotion, loyalty, faithfulness; engagement, commitment; dedication; reverence, service, homage; the condition of the whole being of a Bhakta whose mind and body are totally absorbed in the object of his worship and remain continually directed or oriented towards it; the object of such worship can be an anthropomorphic deity, a symbol, a name, an image, a concept, an abstraction, or the non-discursive or inconceivable "Whole Being" itself.

Bhakti-Marga:

derives from the above; literally, "the way of devotion" or "devotion as the path by which God is realized (by individuals or by a community of devotees)". In reading Tukaram, Bhakti should be usually read as the Bhakti of Vishnu by any of his one thousand names that are also his epithets but specifically in the form of Vitthal, or Vithoba; see Varkari, Vitthal, Pandharpur, "the Brick",etc.

Bhakti Rasa:

would literally mean "the juice of Bhakti" or "(the uninterrupted flow of) the feeling of devotion"; "rasa" in classical Sanskrit poetics is active feeling, emotion, something akin to "juice" in a physiological sense, thus a somatic action or effect; but the poetics itself is diversely linked and interpreted in terms of religious esotericism, yoga, and mysticism; the cryptic precept, "Raso vai sah" means, "He is the very rasa" which, loosened by paraphrase would mean "God or the Whole Being is Himself that spontaneous flowing juice"; one is making this slight digression because the pioneer Marathi poet-saint Jnanadev was an initiate in the Kashmir Shaiva tradition, the same school of thought to which the great mystic philosopher and poetician, Abhinavagupta belonged; Jnanadev was a yogi of the Natha Sect; how he came to worship the deity Vithoba, seen as a form of Vishnu, and became a founder of the Varkari Bhakti movement is a perennial mystery; but the "rasa" or "feeling" part of Bhakti, the sensuous and palpable form of worshipping God as a devotee, focused on a specific image and a "name", begins with Jnanadev and his contemporaries; poetry and music, singing songs and chanting, were believed to produce a distinct "rasa" or "flow of feeling", of oneness with God; this is the "rasa" or "state of being in a continuous flow" that makes Varkaris sing, dance, chant the name of God, and create that "total theatre" where everybody is a part of the grand performance of worship; the pilgrimage to Pandharpur and the festival of Vithoba there have to be witnessed to get an idea of how" Bhakti-rasa" a distinct universe of feeling, envelops the "Bhaktas" with a sense of communion; Tukaram's poetry is described as a poetry of" Bhakti-rasa" which includes a wide range of emotions and different personae depicting the devotee's many-faceted relationship with God; it is useful to bear this in mind because the Varakari Bhakta may be viewing Tukaram's poetry as the poetry of Bhakti-rasa, which is not quite the same feeling that we experience ourselves in our normal life and assume that others experience; nor do we associate such a feeling with poetry and its impact.

Brahma:

the "Creator"; one of the gods in the Hindu pantheon; he is depicted in the Puranas as having sprung from a lotus rising out of the navel of Vishnu.

Brahman:

original Sanskrit form of the word which is Brahma in Marathi; neuter gender; often translated as "the Supreme Being" etc., and variously interpreted by Vedantic philosophers and commentators; it is at once the primordial as well as the ultimate condition of being, a concept of "being-in-itself' which is beyond determination, definition or description. As such, it is a paradoxical concept of the inconceivable, which is the source of all phenomena and all possible concepts thereof. It is used in the sense of "autonomous self' or "the principle of spontaneous creation, existence, and dissolution". In mystical thought, "Brahman" can be experienced as "bliss" or "beatitude" or "a sense of boundless being". It is "ecstasy" in terms of its outward signs and "ecstasy" in terms of "self- contained sense of bliss". During the last decade of his life, Tukaram unexpectedly met Babaji, a liberated yogi, who initiated him into an experience of such "beatitude". Tukaram's evolution from being a Bhakta to becoming a mystic is clearly seen in his poems. There was never a contradiction between his worship of Vithoba and his yearning to experience beatitude or "oneness with All Being". There are people, in fact, who believe that Tukaram's body simply disintegrated and returned to the state of absolute, unconditioned being, leaving no trace of its material form and identity. I have no comment to offer on this except that if true, it would be real poetic justice.

Brahmin:

the highest among the castes; considered pure and chaste; the "twice-born" priestly caste that has a privileged access to the scriptures and the sole right to recite, teach, and interpret them; they conduct religious ceremonies, perform rites, and adjudicate matters and disputes concerning dharma of all Hindus; in Tukaram's time, Brahmins in Maharashtra considered all the other castes as either "non-caste" or "outside the sacred circle" or as Shudras: causing pollution in varying degrees; Tukaram describes himself as a Shudra and a Yatiheen, which means Jatiheen, or low-born, and pointedly mentions that the Brahmins would not even concede him the right to read and write, let alone discuss spiritual matters; he also attacks depravity among Brahmins and holds them responsible for corruption of religion as well as ethics in personal and social life; Tukaram propounds that anyone who is pure in spirit is a true Brahmin and accidents of birth have nothing to do with it; in Tukaram's view any individual who is God-oriented or tuned to "the Whole Being" is a Brahmin or the Brahman-oriented person, because "caste" is a quality of mind determined by purity of awareness rather than by any physical or material property or criterion

Glossary II of IV (Says Tuka) - Dilip Chitre

Brick, the:

this has been used as a proper noun because it refers to "the Brick" on which the image of Vitthal at Pandharpur stands and is an integral part of the iconography of Vitthal; the Marathi word for brick is "veet", and some folk-etymologists would derive the word Vitthal itself from it; the mythological significance of "the Brick" , is the following story: Pundalik, a resident of Pandharpur and a devotee of Vishnu-Vitthal was visited by God Himself, who had heard of Pundalik's total dedication; Pundalik was so absorbed in his own work that he threw a brick that was handy in the direction of his divine visitor, asking him to stand; after that, Pundalik forgot all about God whom he had kept waiting, while he remained absorbed in his own work; God would not leave without Pundalik's permission; he has remained standing on the brick ever since; twenty-eight eons are said to have elapsed since Pundalik asked God to wait on the brick; this is how God is found in Pandharpur where his devotees can visit Him; "the Brick" may mean Vitthal Himself in Tukaram's poetry; Tukaram worships Vitthal's feet, which are placed on "the Brick", in humility; because God stands on it "the Brick" itself is sacred. "the Brick" is also the "base" or "foundation" of God in this world, and as such it is a symbol of Bhakti itself, which is the foundation of the Whole Being or Brahman for the Bhakta; "the Brick" is also a symbol of God's patient, obedient, and respectful attitude towards a true Bhakta,epitomized by the story of Pundalik; the Varkari Bhakta-poets consider Pundalik as the arch-Bhakta and founder of the sacred site and image at Pandharpur.

Chandal:

another term designating a low-caste, a Shudra; originally, a mixed caste of illegitimate progeny of Shudra male and Brahmin female parents; as such, bastards born of prohibited intercaste liasons; a derogatory term used for the lowest born, for the unscrupulous, the sinful, the wicked, the corrupt, and the criminal-minded.

Colour:

the colour of Vishnu is dark blue, the colour of the sky itself, which is the colour of his avatara, Krishna; Krishna literally means "the dark one" or even "the black one"; sometimes, in poetry, the colour of Krishna is compared to "a dark blue rain cloud", a monsoonal association with its evocative effect on the Indian mind and its pastoral significance for herdsmen; Krishna was a herdsman, too; the colour of the image of Vitthal is black; the dhotar or loin-garment of Vitthal is yellow silk; the name Pandurang, used for Vithoba or Vitthal was first used in 1270 according to Deleury: its origin is obscure; but Pandurang is close to the Sanskrit word "pandura", which means "yellowish-white" or "fawn-coloured"; in both Sanskrit and Marathi, "anga" means body, Another significance of colour needs to be pointed out in the context of Tukaram's visual imagery, especially when he is describing his experience of beatitude: when Tukaram meditates on Vitthal's form, the image becomes a formless expanse of luminous blue that turns into an intense incandescence; but when he describes the effect of his initiation into the state of beatitude induced by his Guru Babaji, Tukaram describes a state of ecstasy in which he begins to see luminous ripples in five colours: red, yellow, blue, white, and black: these colours vibrate, pulsate, and keep changing from one into the other in a rhythmic manner.

One more thing to remember is that in Marathi the verb "rangane" which means "to be coloured" also refers to the experience of being absorbed in any activity in such a way that one's very appearance is "coloured" by it; this applies to devotion, worship, the act of singing and dancing, the act of chanting the names of God, and in Tukaram's case, the act of creating poetry or "speaking" in that special sense; in all these, "one is coloured by what one thinks of and does" or "one's very being is coloured by one's awareness"; any performance that becomes increasingly exciting or absorbing is described in Marathi, literally, as something "that is becoming more and more colourful" or "is gaining colour"; "getting coloured by Bhakti- rasa" is another typical expression.

Dehu:

Tukaram's native village; this is situated on the banks of the river Indrayani; it is part of the earliest or one of the earliest-known agricultural belts in Maharashtra, it is accessible by rail from Bombay or Pune via the Dehu Road Railway Station; by road, it is just an hour's drive from Pune; Tukaram's ancestral house with its shrine is still here and his descendants live there; it also has another temple of Vithoba and several smaller shrines; "the pool" in the river Indrayani where Tukaram's manuscripts were sunk and then miraculously restored is one of the landmarks; another landmark is the place at which Vishnu's chariot of light is believed to have descended to lift Tukaram bodily off to heaven; Dehu, along with Pandharpur and Alandi, is one of the three sacred places Varkari pilgrims regularly visit; the Bhamachandra hill, where Tukaram meditated for fifteen days and received enlightenment, is also near Dehu and so is the Bhandara Hill where Tukaram wrote his poems; the landscape and the people Tukaram has described belong to Dehu, which still retains recognizable traces of its features as they must have been in Tukaram's time.

Deva:

also "dev" in Marathi; God; also god or gods; Tukaram employs this word in different senses; often, it is a form of address to the image of Vitthal, but to Tukaram Vitthal not only contains the specific form in which Vishnu visited Pandharpur and stood on "the Brick" at Pundalik's instance but also Vishnu in all his avataras, including that of the Buddha to whom Tukaram makes a reference in a poem not translated here; the mythology of Vishnu and the lore of Krishna are both included in Tukaram's frame of reference; but Tukaram's God is also the Supreme Being in a monotheistic sense, the Creator and the Ruler, not dissimilar from the Judaeo-Christian-Islamic "Father"; but Tukaram uses all three genders for God; at the highest level, he conceives God as a form of total being, the Whole Being or the Cosmic Self of which the human individual is a part; Tukaram's mysticism had both native Marathi and traditional Hindu origins but it was also influenced "by Sufi thought, and Buddhism; the traces of these influences are subtly diffused over his work; one has found an existentialist current in Tukaram's thought that is constant and growing; though he obviously began as 'a simple devotee, he evolved into a monotheistic mystic, and finally into a mystic who went beyond theism itself; in some poems, Tukaram has described his whole relationship with God as a game of "make-believe" or as "play-acting", assigning roles that are mutually reversible. In each poem, God has a specific image and role; there are no fixed rules or definitions that Tukaram follows; it is worth bearing in mind that in many poems, Tukaram sees himself as an irreverent atheist or as one making fun of an anthropomorphic idea of God.

Ekadashi: